Abstract

Purpose

To examine gender differences in the associations between childhood adversity and different types of substance use disorders and whether gender moderates these relationships.

Methods

We analyzed data from 19,209 women and 13,898 men as provided by Wave 2 (2004–2005) of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) to examine whether gender moderates the associations between childhood adversity and DSM-IV defined lifetime occurrence of alcohol, drug, and polysubstance-related disorders. We used multinomial logistic regression, weighted to be representative of the US adult civilian, noninstitutionalized population, and we calculated predicted probabilities by gender, controlling for covariates. To test which specific moderation contrasts were statistically significant, we conducted pair-wise comparisons corrected for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni’s method.

Results

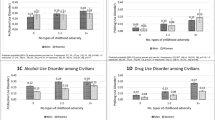

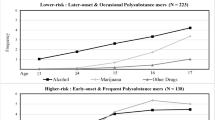

For each type of substance use disorder, risk was increased by more exposure to childhood adversity, and women had a lower risk than men. However, moderation effects revealed that with more experiences of childhood adversity, the gender gap in predicted probability for a disorder narrowed in relation to alcohol, it converged in relation to drugs such that risk among women surpassed that among men, and it widened in relation to polysubstances.

Conclusions

Knowledge regarding substance-specific gender differences associated with childhood adversity exposure can inform evidence-based treatments. It may also be useful for shaping other types of gender-sensitive public health initiatives to ameliorate or prevent different types of substance use disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Afifi TO, Henriksen CA, Asmundson GJ, Sareen J (2012) Childhood maltreatment and substance use disorders among men and women in a nationally representative sample. Can J Psychiatry 57(11):677–686

Ahern J, Balzer L, Galea S (2015) The roles of outlet density and norms in alcohol use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 151:144–150

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC

Back SE, Payne RL, Simpson AN, Brady KT (2010) Gender and prescription opioids: findings from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Addict Behav 35(11):1001–1007

Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L et al (1994) Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psychiatry 151(8):1132–1136

Brady KT, Back SE, Greenfield SF (2009) Women and addiction: a comprehensive handbook. The Guilford Press, New York

Briere J, Hodges M, Godbout N (2010) Traumatic stress, affect dysregulation, and dysfunctional avoidance: a structural equation model. J Trauma Stress 23:767–774

Cavanaugh CE, Petras H, Martins SS (2015) Gender-specific profiles of adverse childhood experiences, past year mental and substance use disorders, and their associations among a national sample of adults in the United States. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50(8):1257–1266

Choi NG, DiNitto DM, Marti CN, Choi BY (2016) Association of adverse childhood experiences with lifetime mental and substance use disorders among men and women aged 50+ years. Int Psychogeriatr 26:1–14 (Epub ahead of print)

Dong M, Anda RF, Dube SR, Giles WH, Felitti VJ (2003) The relationship of exposure to childhood sexual abuse to other forms of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction during childhood. Child Abuse Negl 27(6):625–639

Dube SR, Anda RF, Whitfield CL et al (2005) Long-term consequences of childhood sexual abuse by gender of victim. Am J Prev Med 28(5):430–438

Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman DP, Giles WH, a RF (2003) Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: the adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics 111(3):564–572

Enoch, M.A., 2011. The role of early life stress as a predictor for alcohol and drug dependence. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 214(1):17–31

Evans E, Grella C, Washington D, Upchurch D (2017) Gender and race/ethnic differences in the persistence of alcohol, drug, and poly-substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend (in press)

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D et al (1998) Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 14(4):245–258

Fleming J, Mullen PE, Sibthorpe B, Bammer G (1999) The long-term impact of childhood sexual abuse in Australian women. Child Abuse Negl 23(2):145–159

Gjerde F, Block J, Block JH (1988) Depressive symptoms and personality during late adolescence: gender differences in the externalization-internalization of symptom expression. J Abnorm Psychol 97(4):475–486

Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R (2003) The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend 71(1):7–16

Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Chou SP et al (2009) Sociodemographic and psychopathologic predictors of first incidence of DSM-IV substance use, mood and anxiety disorders: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Mol Psychiatry 14:1051–1066

Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA et al (2010) Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67(2):113–123

Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM et al (2007) Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: a review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend 86(1):1–21

Hasin DS, Grant BF (2016) The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Waves 1 and 2: review and summary of findings. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50(11):1609–1640

Hecksher D, Hesse M (2009) Women and substance use disorders. Mens Sana Monogr 7(1):50–62

Hernán MA, Robins JM (2016) Causal Inference. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC, forthcoming. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/miguel-hernan/causal-inference-book/. Accessed 28 Nov 2016

Jääskeläinen M, Holmila M, Notkola IL, Raitasalo K (2016) Mental disorders and harmful substance use in children of substance abusing parents: a longitudinal register-based study on a complete birth cohort born in 1991. Drug Alcohol Rev 35(6):728–740

Keyes KM, Grant BF, Hasin DS (2008) Evidence for a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population. Drug Alcohol Depend 93(1–2):21–29

Leadbeater BJ, Kuperminc GP, Blatt SJ, Hertzog C (1999) A multivariate model of gender differences in adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. Dev Psychol 35(5):1268–1282

Lev-Ran S, Le Strat Y, Imtiaz S, Rehm J, Le Foll, B (2013) Gender differences in prevalence of substance use disorders among individuals with lifetime exposure to substances: results from a large representative sample. Am J Addict 22(1):7–13

Lewis T, McElroy E, Harlaar N, Runyan D (2016) Does the impact of child sexual abuse differ from maltreated but non-sexually abused children? A prospective examination of the impact of child sexual abuse on internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Child Abuse Negl 51:31–40

Mack KA (2013) Drug-induced deaths—United States, 1999–2010. MMWR Surveill Summ 62(Suppl 3):161–163

McLaughlin KA, Conron KJ, Koenen KC, Gilman SE (2010) Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: a test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychol Med 40(10):1647–1658

McManama O’Brien KH, Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, LeCloux M (2015) Childhood exposure to a parental suicide attempt and risk for substance use disorders. Addict Behav 46:70–76

Mendle J, Leve LD, Van Ryzin M, Natsuaki MN (2014) Linking childhood maltreatment with girls’ internalizing symptoms: early puberty as a tipping point. J Res Adolesc 24(4):689–702

Mullen PE, Martin JL, Anderson JC, Romans SE, Herbison GP (1996) The long-term impact of the physical, emotional, and sexual abuse of children: a community study. Child Abuse Negl 20(1):7–21

Myers B, McLaughlin KA, Wang S, Blanco C, Stein DJ (2014) Associations between childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and past-year drug use disorders in the National Epidemiological Study of Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Psychol Addict Behav 28(4):1117–1126

Najavits LM (2009) Psychotherapies for trauma and substance abuse in women: review and policy implications. Trauma Violence Abuse 10(3):290–298

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (2010) alcohol use and alcohol use disorders in the United States, A 3-Year Follow-Up: Main Findings from the 2004–2005 Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol And Related Conditions (NESARC). U.S. Alcohol Epidemiologic Data Reference Manual, Volume 8, Number 2. NIH Publication No. 10–7677. Retrieved November 28, 2016 from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/NESARC_DRM2/NESARC2DRM.pdf

Pilowsky DJ, Keyes KM, Hasin DS (2009) Adverse childhood events and lifetime alcohol dependence. Am J Public Health 99(2):258–263

Rothman EF, Edwards EM, Heeren T, Hingson RW (2008) Adverse childhood experiences predict earlier age of drinking onset: results from a representative US sample of current or former drinkers. Pediatrics 122(2):e298–e304

Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP et al (2008) The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend 92(1–3):27–36

Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB (1996) The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): development and preliminary psychometric data. J Fam Issues 17(3):283–316

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2015) Behavioral health trends in the United States: results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 15-4927, NSDUH Series H-50). Retrieved December 6, 2016 from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR1-2014/NSDUH-FRR1-2014.pdf

Tai B, Volkow ND (2013) Treatment for substance use disorder: opportunities and challenges under the affordable care act. Soc Work Public Health 28(3–4):165–174

Warner LA, Alegria M, Canino G (2004) Remission from drug dependence symptoms and drug use cessation among women drug users in puerto rico. Arch Gen Psychiatry 61(10):1034–1041

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: NESARC criteria for diagnosis of alcohol and drug abuse and dependence

The following information is provided by the NESARC Data Reference Manual (NIAAA, 2010).

Alcohol A diagnosis of DSM-IV alcohol abuse requires that a person show a maladaptive pattern of alcohol use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as demonstrated by meeting at least one of the four abuse criteria. A diagnosis of alcohol dependence requires that a person meet at least three of the seven dependence criteria. Because the DSM-IV considers alcohol dependence a syndrome, symptoms comprising three or more dependence criteria have to cluster within any 12-month period. The withdrawal criterion of the alcohol dependence diagnosis was measured as a syndrome, requiring at least two positive symptoms of withdrawal as defined in the DSM-IV, or one positive symptom of withdrawal relief/avoidance (i.e., taking a drink or medicine or drug to avoid or get over bad aftereffects of drinking). A person who meets criteria for both abuse and dependence is classified in the dependence category.

Drugs NESARC contains questions that allow for a diagnosis of drug use disorders according to the DSM-IV. The drug use disorder diagnoses assessed in the NESARC include DSM-IV diagnoses of abuse and dependence for each of 10 separate categories of medicine and illicit drugs. These categories include: sedatives, tranquilizers, opiates (other than heroin or methadone), stimulants, hallucinogens, cannabis, cocaine (including crack cocaine), inhalants/solvents, heroin, and other drugs. Sedatives, tranquilizers, opiates, and stimulants were counted only if used without or beyond the bounds of a prescription.

The DSM-IV criteria for drug-specific abuse and dependence are similar to those for alcohol abuse and dependence, but vary slightly across drugs. At least one of the four abuse criteria is required for a drug-specific abuse diagnosis, and in general, at least three of the seven dependence criteria are required for a drug-specific dependence diagnosis. The withdrawal criterion is not used for cannabis, hallucinogen, or inhalant dependence diagnosis. For data tables presented in this manual, a diagnosis of any drug abuse or dependence results from drug-specific diagnoses made for any of the 10 separate medicine/drug categories in a 12-month period.

Appendix 2: Operationalization of childhood adversity

NESARC assessed adverse childhood events occurring before age 18 using questions that were a subset of items from the Conflict Tactics Scale [41] and the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire [5]. Respondents were asked to respond to all questions pertaining to abuse or neglect (except emotional neglect) on a five-point scale (never, almost never, sometimes, fairly often, or very often). Emotional neglect questions employed an alternative five-point scale of never true, rarely true, sometimes true, often true, or very often true. All questions pertaining to general household dysfunction required yes/no responding (except questions regarding having a battered mother, which used the same scale as for the items on abuse or neglect above) (Table 3).

We considered 11 types of childhood adversity, which we defined to be consistent with definitions employed in the Adverse Childhood Experiences study [10, 12] and epidemiological research on childhood adversity [1].

-

1.

Physical abuse was defined as a response of “sometimes” or greater to either question when asked how often a parent or other adult living in the respondent’s home (1) pushed, grabbed, shoved, slapped, or hit the respondent; or (2) hit the respondent so hard it left marks or bruises, or caused an injury.

-

2.

Emotional abuse was identified as a response of “fairly often” or “very often” to any question when asked how often a parent or other adult living in the respondent’s home (1) swore at, insulted, or said hurtful things to the respondent; (2) threatened to hit or throw something at the respondent (but did not do it); or (3) acted in any other way that made the respondent afraid he/she would be physically hurt or injured.

-

3.

Sexual abuse was examined using four questions that examined the occurrence of sexual touching or fondling, attempted intercourse, or actual intercourse by any adult or other person when the respondent did not want the act to occur or was too young to understand what was happening. Any response other than “never” on any of the questions was coded as sexual abuse.

-

4.

Physical neglect was defined as any response other than “never” to five questions that asked about experiences of being made to do difficult or dangerous chores, being left unsupervised when too young to care for self or going without needed clothing, school supplies, food, or medical treatment.

-

5.

Emotional neglect was defined by five questions asking whether respondents felt a part of a close-knit family or whether anyone in the family of origin made the respondent feel special, wanted the respondent to succeed, believed in the respondent, or provided strength and support. Following prior research, the five items were reverse-scored and summed; scores of 15 or greater were coded as emotional neglect [1, 10, 12].

-

6.

Parental substance abuse was a form of household dysfunction that was assessed with two questions asking whether a parent or other adult living in the home had a problem with alcohol or drugs. A response of “yes” to either question was defined as parental substance abuse.

-

7.

To characterize the history of having a battered mother, respondents were asked whether the respondent’s father, stepfather, foster/adoptive father, or mother’s boyfriend had ever done any of the following to the respondent’s mother, stepmother, foster/adoptive mother, or father’s girlfriend: (1) pushed, grabbed, slapped, or threw something at her; (2) kicked, bit, hit with a fist, or hit her with something hard; (3) repeatedly hit her for at least a few minutes; or (4) threatened to use or actually used a knife or gun on her. Any response of “sometimes” or greater for questions 1 or 2, or any response except “never” for questions 3 or 4, was defined as having a battered mother.

-

8.

For the other measures of household dysfunction, respondents were asked to answer with either “yes” or “no” whether a parent or other adult in the home (1) went to jail or prison; (2) was treated or hospitalized for mental illness; (3–4) attempted or actually committed suicide. A response of “yes” to any of these questions was coded as household dysfunction.

Appendix 2 Table 4 shows gender differences in experiences with different types of childhood adversity.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Evans, E.A., Grella, C.E. & Upchurch, D.M. Gender differences in the effects of childhood adversity on alcohol, drug, and polysubstance-related disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 52, 901–912 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1355-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1355-3