Abstract

Purpose

Research on predictors of young children’s psychosocial well-being currently relies on adult-reported outcomes. This study investigated whether early family circumstances and parenting predict 7-year-olds’ subjective well-being.

Methods

Information on supportive friendships, liking school and life satisfaction was obtained from 7-year-olds in one Growing Up in Scotland birth cohort in 2012–2013 (N = 2869). Mothers provided information on early childhood factors from 10 to 34 months, parenting (dysfunctional parenting, home learning and protectiveness) from 46 to 70 months, and 7-year-olds’ adjustment. Multivariable path models explored associations between early childhood factors, parenting and 7-year-olds’ subjective well-being. Supplementary analyses compared findings with those for mother-reported adjustment.

Results

In a model of early childhood factors, maternal distress predicted less supportive friendships and lower life satisfaction (coefficients −0.12), poverty predicted less supportive friendships (−0.09) and remote location predicted all outcomes (−0.20 to −0.27). In a model with parenting added, dysfunctional parenting predicted all outcomes (−10 to −0.16), home learning predicted liking school (0.11) and life satisfaction (0.08), and protectiveness predicted life satisfaction (0.08). Effects of maternal distress were fully mediated, largely via dysfunctional parenting, while home learning mediated negative effects of low maternal education. Direct effects of poverty and remote location remained. Findings for mother-reported child adjustment were broadly similar.

Conclusions

Unique prospective data show parenting and early childhood impact 7-year-olds’ subjective well-being. They underline the benefits for children of targeting parental mental health and dysfunctional parenting, and helping parents develop skills to support children at home and school.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the last decade, there has been growing recognition of the importance of understanding children’s subjective well-being. Subjective well-being covers both affective and cognitive dimensions, respectively concerned with experiencing emotions and evaluating one’s life, including overall life satisfaction [1]. Young children’s emotional states may be relatively transitory, so in common with most research we focus on cognitive aspects of subjective well-being here. Children’s own perspectives permit corroboration of adult-reported socio-emotional development, and are likely to provide unique insights on needs and priorities that could otherwise be overlooked. Secondary school-age children’s views are now routinely included in cross-national comparisons of overall child well-being, and although rankings of life satisfaction are broadly associated with objective socio-economic indicators [2], there are poorly understood anomalies. For instance, subjective life satisfaction is generally associated with public expenditure on families and education, but in the Netherlands, children appear much happier than might be predicted from their country’s spending [3]. This has led to debate on whether social policies can really improve children’s happiness. Early intervention may be most cost-effective, but as a first step we need to be able to ascertain the main determinants of subjective well-being from early childhood. Our current knowledge of subjective well-being is mainly based on children aged 10 or older and lacks prospective information from the early years (though see two recent cross-sectional studies of 7- and 9-year-olds [4, 5]). Data collected by Growing Up in Scotland (GUS), a large birth cohort study enables us, for the first time, to investigate the influence of early family circumstances on the views of young children themselves. To explore possible origins of social inequalities in young children’s subjective well-being, our study develops an ecological risk model [6].

Family risk factors

Theoretical and empirical work suggests that social relationships, health and income constitute important determinants of life satisfaction among adults, with evidence from a number of countries pointing to the primacy of social relationships [7]. Our ecological model focuses on the family setting, being generally where the first foundations will be laid for social relationships critical to future happiness; indeed, happiness with family life was the most important correlate of life satisfaction in a large UK study of 8- to 17-year-olds [8]. We draw on key parental and household resources already established as important for children’s mental health. Several indicators of low family economic and psychological resources, such as poverty, poor parental health, substance use, low parental education and single parenthood, are often found to co-occur, but may nonetheless represent independent threats to socio-emotional adjustment [9–12]. There is some evidence that parental mental health [13, 14], substance use [15] and socio-economic status [16], together with family income [17–19] and structure [20–22], also affect older children’s subjective well-being. However, almost all the studies on older children have had a cross-sectional design; and findings in relation to factors found important across studies are inconsistent. Further longitudinal studies, including on younger age groups, are required to supplement this evidence base and inform our understanding of how social inequalities in children’s subjective well-being may develop.

Home location risk factors

We extend the ecological model beyond parent and household characteristics to consider whether home location influences young children’s subjective well-being. As for family setting, we select aspects of location already implicated in young children’s socio-emotional adjustment. Area deprivation has been linked to poor socio-emotional adjustment in several studies of young children [23, 24] although in some instances its effects are explained by family socio-economic status [25]. Less is known about the effects of urban–rural location on young children’s adjustment. Some research has shown differences in behavioural and emotional problems according to degree of urbanisation. One US study found more behavioural problems in rural areas [26], while an English study found fewer behavioural and peer problems in less sparse rural areas compared to either more urban or predominantly rural areas, and fewer emotional problems in areas with an urban/rural mix compared to other area types [27]. Elsewhere, clear urban–rural differences have not been found [28, 29]. In relation to area effects on subjective well-being, again we find that existing studies are confined to older age groups. An ecological assets model of adolescent life satisfaction has underlined the importance of social relationships in different domains including school and neighbourhood as well as the family [30], while limited research on the effects of urbanisation suggests lower adolescent subjective well-being among rural populations [31, 32].

Pathways from family and home location risk factors via parenting

Our ecological model is developed further by examining possible pathways from early childhood influences to children’s subjective well-being, via parenting. Family processes, through which a child develops and sustains relationships with parents, and others, are theorised as dependent on contextual stress and support [33]. In selecting family processes as potential mediators of early childhood factors within the family setting, we draw on two models seeking to explain socio-economic inequalities in children’s development: family investment and family stress [34]. In the case of family investment, economic resources are posited as directly affecting the quality of parenting, extending beyond financial investment to cover parental involvement with the child’s upbringing, including time spent with the child. In the family stress model, economic resources are posited as affecting the quality of parenting indirectly, via parental mental health. In relation to the family investment model, we examine home learning, such as looking at books, drawing and singing. These activities help children adjust to school learning [35], and are likely to bolster emotional engagement with school. Importantly, however, research has also suggested a connection between parental provisions of enjoyable stimulation and reduced socio-emotional problems, as well as mediation of the effects of early socio-economic disadvantage on these outcomes [36–39]. This suggests that parental investment in home learning may help promote increased subjective well-being more generally (i.e. beyond any effect on school adjustment), perhaps because children are less bored and frustrated, and have a greater sense of being nurtured. Second, in relation to the family stress model, we examine dysfunctional parenting characterised by multiple challenges, such as high levels of parent–child conflict, parenting stress and a chaotic home environment. These aspects of dysfunctional parenting have been found to be associated with child behavioural and emotional problems, as well as channelling some of the associations found for socio-economic disadvantage, single parenthood or poor parental mental health with these problems [11, 40–43]. It is therefore plausible to suggest that dysfunctional parenting may lead to lower child subjective well-being, as well as providing a pathway linking early childhood disadvantage with well-being.

Looking beyond the family setting, neighbourhood characteristics may also shape parenting in various ways. Local institutions and resources may facilitate better parenting via provision of health and welfare services, stimulating environments, such as libraries, parks and sports facilities, and opportunities for socialisation. In addition, other adults living in the neighbourhood may provide families with role models and emotional or instrumental support for parenting. Evidence that neighbourhood effects on children’s well-being may operate via parenting comes from a US study, where effects of neighbourhood deprivation on children’s socio-emotional adjustment, independent of family-level socio-economic status and risk, were mediated by less supportive parenting [44]. In our study, we might expect some area-level influences on children’s subjective well-being to be explained via processes linked to family investment and stress. However, neighbourhood deprivation and urbanisation may also be associated with differences in parental perceived safety in relation to social disorder, “stranger danger” and road traffic, leading to differences in children’s outdoor physical activity [45, 46]. We therefore consider a third aspect of parenting, protectiveness of the child playing outdoors, which may provide an additional pathway for area effects on children’s subjective well-being linked to parental safety concerns. Parental protectiveness might itself exert some negative influence on well-being, by limiting children’s independence and their ability to form friendships with children outside school hours. Alternatively, and especially for young children, parental protectiveness is likely to enhance perceptions of being valued and cared for, and may shield them from adverse or challenging situations: consequently, protectiveness seems more likely to be associated with greater, rather than lower, overall child subjective well-being.

Alternative pathways from family and home location risk factors

Although parenting processes may channel many of the effects of early childhood on school-age children’s subjective well-being, it is likely that stable family circumstances will also over time begin to affect the child in other ways. Alternative mechanisms for effects of family-level factors such as living in poverty or without a resident father could involve social comparison, although young children may not have highly developed expectations, and may be relatively unaware of differences between their own family circumstances and those of other children [47]. It has also been argued that children’s natural resilience may allow adaptation to all, but the most extreme family circumstances [48]. In the case of poverty, qualitative research with low-income families suggests children of all ages acknowledge its impact, but they also show adaptation to its effects [49].

There may also be other mechanisms for effects of home location on subjective well-being. Some positive pathways from lower levels of neighbourhood deprivation or urbanisation have been found. Both lower area deprivation and moderate rurality in England have been found to influence children’s socio-emotional adjustment, via improved school quality [24, 27]. A Swedish study found children’s lower perceptions of community trust and safety in urban areas was associated with lower subjective well-being, compared to rural areas [50]. Rurality might also benefit children via closer proximity to green spaces; but although there is some evidence of benefits of green spaces within residential environments for adult mental health, little is known in relation to children [51]. Moreover, a recent review has challenged adult perspectives of the idyllic rural childhood, finding that children often see the rural environment as restrictive and unsafe [52]. Negative pathways might also exist from remoteness to children’s subjective well-being. Pathways linked to increased travel times might involve social isolation and poor access to health services implicated in adult studies [53, 54]. Social comparisons may also have a role to play if children in remote areas are sensitive to differences in their lives compared to the vast majority living near urban centres.

Our study investigates early childhood and parenting predictors of three aspects of 7-year-olds’ subjective well-being: overall life satisfaction, enjoyment of school and supportive friendships. Based on the existing research on children’s psychosocial adjustment, we hypothesise that the two strongest early predictors of lower subjective well-being will be maternal distress (poor mental health and substance use), and family poverty. As the ecological model of child development puts parents at the core of young children’s socialisation, we expect that more proximal effects of parenting processes will, to a large extent, channel the more distal effects of early life factors on subjective well-being. Our focus is on children’s own views, but since these are relatively untested for this young age group we also explore mothers’ reports of child adjustment in supplementary analyses.

Methods

Data were from the first birth cohort of the Growing Up in Scotland study, a nationally representative cohort of families with children born between June 2004 and May 2005. Details of the sampling framework are provided elsewhere [55]. Baseline data were gathered from 5217 families during 2005–2006, when children were 10 months old, and these families were followed up annually for 5 years (to 70 months), and then after 2 years (94 months, N = 3,456). This study used information obtained in 2012–2013 from computer-assisted personal interviews conducted with the main carer from 10 to 70 months; and from the cohort child at 94 months using an audio computer-assisted self-completion questionnaire. The analysis sample was restricted to cases where the child completed a questionnaire at 94 months, the child was a singleton birth, and the mother was the main carer interviewed at all previous survey sweeps (N = 2869).

Measures

Outcome measures

Child-reported information at 94 months was used to create three latent (not directly observed) constructs related to subjective well-being. Life satisfaction used five items from Huebner’s Student Life Satisfaction Scale [56] concerning whether the child feels he/she has a good life, has what he/she wants in life, his/her life is just right, wishes life was different, and feels life is going well (indicator loadings 0.46–0.68). Liking school and supportive friendships respectively used items from the school and friends domains of the Multidimensional Life Satisfaction Scale [57]; liking school used three items (“I enjoy learning at school”, “I hate school”, “I look forward to going to school”, loadings 0.64–0.84); supportive friendships used two items (“My friends are mean to me”, “My friends are nice to me”, loadings 0.71 and 0.48).

Mother-reported outcomes at the 94 month interview used the five-item subscales of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire [58] to measure child emotional problems and child peer relationship problems, Cronbach’s alphas 0.68 and 0.65, respectively; and two items designed specifically for the study to measure school adjustment, based on how often the child looked forward to going to school, and how often he/she was reluctant to go (alpha = 0.50).

Main predictors

These are outlined below. Further details are provided in a supplementary file (S1), which also provides information on additional covariates included in the analysis as potential confounders of predictor-outcome associations (child gender, first born status, general health at 10–22 months, developmental delay at 22 months, and cognitive score at 34 months; maternal ethnic group, age at birth of the child and low physical health at 10 months; and the number of children in the household at 10 months).

Maternal education was reported by mothers at 10 months and classified into four levels: the lowest group comprised mothers obtaining lower-level qualifications at school leaving age, or no qualifications at all; and the highest group comprised mothers with degree level qualifications. Maternal distress was modelled as a latent construct using indicators of poor maternal mental health (10, 22, and 34 months) and illegal drug use (10 and 34 months). Consideration of alternative measurement models indicated that the optimal fit was achieved by a single construct for mental health and drug use. Other available indicators covering smoking and alcohol use were explored, but rejected due to insufficiently high factor loadings, i.e. <0.4. Father absence was defined as the father being absent from the household at one or more of the 10, 22 and 34 month surveys. Family poverty was a latent construct using indicators of low family income (≤60 % of UK median income) and workless household at the 10, 22, and 34 month surveys. Area deprivation was measured by linking to the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation via home postcode. Two alternative groupings of the Scottish Urban/Rural Classification also linked to home postcode at the 10 month survey were explored: rurality and remoteness. Both groupings contained large urban areas as a reference, and had other urban areas as one comparison group. To explore rurality, we examined two further comparison groups: small towns (combined accessible/remote) and rural (combined accessible/remote). To explore remoteness, these groups were replaced with two alternative groupings: accessible (combined small town/rural) and remote (combined small town/rural). For more details, see Supplementary File S1.

For parenting, home learning was a latent construct based on four home activities at 46, 58, and 70 months: how often the child looked at books, drew pictures, sang nursery rhymes and played at recognising letters and numbers. Dysfunctional parenting was a latent construct based on parent–child conflict, home disorganisation and parenting stress (all at 58 months). Protectiveness was measured directly, based on four items relating to looking after the child playing outdoors (46 months).

Statistical analysis

Structural equation modelling used Mplus version 7.3 [59]. Missing item response was generally extremely low (<1 %) with the exception of information on income, developmental delay and cognitive score (4–6 %). To reduce bias and increase statistical power, missing information was imputed using Mplus multiple imputation facility. Analyses used weighted least squares means and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimation, combining results across 20 imputed data sets. They allowed for the complex survey design and used survey weights to counteract the effects of differential attrition from baseline to 94 months (35 % overall, but 53 % among mothers with low education, 55 % among families with no resident father and 52 % among families reporting the lowest quintile of household income at baseline). There were two main stages to the analyses. First, multivariable regression models explored associations between early childhood factors and 7-year-olds’ outcome measures, including terms to specify covariance between early childhood factors. Second, path models explored whether parenting mediated effects of early childhood factors on child outcome measures. The Mplus Model Indirect function was used to estimate indirect effects of early childhood factors on child outcomes via parenting. Throughout, statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

The distribution of 7-year-olds’ views with respect to questionnaire items on liking school, supportive friendships and overall life satisfaction are shown in Table 1. Most gave positive views of their lives: over all ten items, the proportion supplying one of the two less favourable response options ranged from 7 % “often” or “always” thinking “my friends are mean to me” to 44 % “sometimes” or “never” reporting “I look forward to going to school”. The three latent constructs were significantly correlated with one another. Supportive friends and liking school were more strongly correlated with overall life satisfaction (0.46 and 0.44, respectively) than with each other (0.27).

Unadjusted associations for early childhood factors, parenting and covariates with child- reported outcomes are shown in Table 2. Low maternal education was associated with less liking of school. Maternal distress and family poverty were associated with the child reporting less supportive friendships and lower life satisfaction, with an additional borderline (p = 0.07) association between maternal distress and disliking school. Father absence, area deprivation and rural location were not clearly associated with child outcomes, but remote location was negatively associated with child-reported life satisfaction and liking school (and borderline, p = 0.09 for supportive friendships). Home learning was positively associated with life satisfaction and liking school, protectiveness was positively associated with life satisfaction, and dysfunctional parenting was negatively associated with all three outcomes.

Table 3 shows results of multivariable models. Stage 1 models associations between early childhood factors and child-reported outcomes, adjusting for child gender, birth order, health, developmental delay and cognitive score; mother’s ethnicity, age at birth of child and low physical health; and number of children in the household (covariates not shown). In these models, covariance between family poverty, area deprivation and maternal distress ranged from 0.25 to 0.52 (not shown in Table, all p < 0.001). Maternal distress and family poverty were negatively associated with supportive friendships and lower life satisfaction (borderline for the effect of poverty on life satisfaction, p = 0.075). Remote location was negatively associated with all three outcomes.

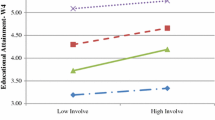

In stage 2, path models allowed for associations between early childhood factors and child outcomes via parenting, as well as direct links between early childhood factors and outcomes. Figure 1 shows significant pathways in the final model: for ease of comparison, standardised coefficients are provided (except for paths from binary measures). Unstandardised coefficients for direct effects of early childhood factors and parenting are shown in Table 3, stage 2. Home learning was predictive of liking school and greater life satisfaction; dysfunctional parenting had significant negative associations with all three outcomes; while protectiveness predicted greater life satisfaction. After allowing for parenting, direct effects of maternal distress were attenuated to non-significance, but the effects of poverty and remote location observed in stage 1 were largely unchanged.

Path model of associations between early childhood factors, parenting and children’s subjective well-being. Model as for Table 3. This figure omits non-significant associations between measures shown here, and all associations between measures shown and additional covariates: child gender, birth order, health (10–22 months), developmental delay (22 months) and cognitive score (34 months); mother’s ethnicity, age at birth of child and low physical health (10 months); and number of children in the household. With the exception of pathways from binary measures (low maternal education, father absence, remoteness), to allow comparison of pathways figures shown here (unlike Table 3) represent standardised coefficients with *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Despite the non-significant direct effect of maternal distress in the final model, it had indirect associations with children’s more negative evaluations of friends, school and life, via more dysfunctional parenting (Fig. 1; Table 4). Table 4 also shows smaller indirect effects of low maternal education and father absence on lower life satisfaction via dysfunctional parenting. There were additional negative indirect effects on well-being from low maternal education via lower home learning. Lastly, opposing pathways via protectiveness were found. While area deprivation produced a small positive indirect effect on life satisfaction via greater protectiveness, maternal distress and remote location both produced corresponding negative indirect effects. A sensitivity analysis (not shown) exploring the effect of restricting indicators of the maternal distress construct to measures of low mental health (i.e. excluding the two indicators of illegal drug use) found that results were unchanged.

A supplementary analysis suggested broad agreement between mother-reported child adjustment at 7 years and child subjective well-being constructs although mother-reported peer and emotional problems did not map neatly on to (respectively) child-reported supportive friendships and life satisfaction. Mother-reported school adjustment was more strongly associated with the child’s own reports of liking school (0.24), than with the other two child constructs (−0.11, −0.16). Mother-reported peer and emotional problems were both negatively associated with child-reported supportive friendships (−0.42, −0.25, respectively) and life satisfaction (−0.31, −0.24, respectively), and less strongly with liking school (−0.12, −0.09). Multivariable analysis (supplementary file S2, stage 1) showed independent effects of all main predictors on one or more mother-reported outcomes, with larger effect sizes than for child-reported outcomes. However, there was no effect of remoteness on mother-reported school adjustment. In stage 2 models, effects of dysfunctional parenting and home learning were similar to those seen for child-reported outcomes, but protectiveness had no effect. Effects of maternal distress were attenuated with the inclusion of dysfunctional parenting, as for child-reported outcomes. There were more remaining significant effects of other early childhood factors. These included effects of low maternal education, family poverty, area deprivation and remoteness on increased peer problems; absent father on reduced school adjustment; and lower maternal education and absent father on increased emotional problems.

Discussion

This study presents unique longitudinal data on the impact of early childhood disadvantage and parenting on 7-year-olds’ own evaluations of friendships, school and life satisfaction. In terms of early childhood influences, our findings suggested that early maternal distress, family poverty and geographical location were predictive of children’s later subjective well-being although the effects of maternal distress were conveyed indirectly, largely via more dysfunctional parenting. The harmful role of dysfunctional parenting emerged most strongly, across children’s ability to form friendships, enjoyment of school and life satisfaction. Home learning predicted greater school enjoyment, and was also important (along with protectiveness) for overall life satisfaction.

Our findings for child-reported outcomes were supported by findings for comparable mother-reported outcomes, particularly with regard to the role of maternal distress, poverty, dysfunctional parenting and home learning. Differences in the strength of associations found are likely to reflect the effects of shared method variance, with mothers reporting outcomes as well as predictors, as well as the imperfect correspondence between attributes assessed by mother and child at the 7-year-old interview. Nonetheless, discrepancies in the pattern seen for child- and mother-reported outcomes with respect to the effects of remoteness and protectiveness support the idea that children’s perspectives will not necessarily tally with those of their parents.

Our study points to the importance of parenting processes for young children’s subjective well-being, adding strength to limited evidence from studies of adolescent life satisfaction [16, 60, 61]. It also indicates the role of parenting in mediating more distal (earlier) influences on the child. The parenting pathways found for dysfunctional parenting corroborate existing research on mechanisms linking family-level risk with child socio-emotional problems via parent–child conflict, home disorganisation and parenting stress [11, 40–43]. Our finding of a path from maternal education to school adjustment and life satisfaction via home learning supports the idea that parental provision of stimulating experiences and materials is linked with socio-emotional adjustment [36–39], as well as with future academic achievement although such activities could also reflect other differences in parenting style and expectations. To our knowledge, parental protectiveness has not been previously linked with child subjective well-being. Its effects on life satisfaction may relate to other aspects of family processes important for socio-emotional adjustment, including attachment [62] and neglectful parenting [63]. However, the small indirect paths found from neighbourhood deprivation via greater protectiveness, and from remoteness via lower protectiveness, are likely to reflect area variation in parental perception of risk [45, 46] and strategies for monitoring children’s outdoor play, as found in some research linking neighbourhood danger to greater parental monitoring of teenagers [64].

Most of the effects of remote location on all three subjective well-being measures could not be accounted for by parenting, suggesting that further explanation is required. The remote study population was highly stable (88 % remaining in remote areas at 7 years), and since previous research suggests older children are more sensitive to the limitations of rural neighbourhoods, it is likely that associations reflect the influence of current location. Others have found that parental perceptions of greater safety and opportunity for outdoor play in rural areas often contrast with children’s own negative views of the countryside [52]. However, we found an effect of remote location (including small towns far from major urban centres) rather than rurality. Contributing factors may include fewer friendship choices, increased travel times and media influences exposing children to wider horizons: more research is required to establish these, and whether our finding foreshadows effects of rurality on lower mental health found for teenagers and young adults [32, 65].

Parenting also failed to account for the effect of poverty. In our study, negative effects of poverty were confined to children’s perceived friendship quality, in contrast to more pervasive effects on older children’s subjective well-being [19]. Our finding may reflect the effect of persistent poverty on 7-year-olds, as two-thirds of families reporting low income in the early years were in similar circumstances at 7 years. Effects may relate to even young children’s perceptions of low social status through inability to afford leisure activities or the latest clothes and gadgets [49].

Limitations of this study include reliance on mothers for sensitive information subject to social desirability and other biases, the sample’s low ethnic diversity, and a lack of information on fathers and on parenting during infancy and toddlerhood. Strengths include the large sample, representative of the Scottish population at baseline, and the use of survey weights to counteract the effect of differential attrition of more disadvantaged groups over the course of the study.

Further data are required from young children to assess other important aspects of subjective well-being, particularly regarding family relationships, and to pursue the impact of both early childhood and concurrent family disadvantage on older age groups. Our study points to the need for a more rounded picture of children’s socio-emotional development, to allow for some differences between child and adult perspectives. It underlines the continued need, in addition to UK social policies reducing child poverty from the late 1990s, to target resources for mothers with poor mental health. It also underscores the damaging effects, from the child’s as well as the parent’s perspective, of dysfunctional parenting. This echoes other findings of spillover effects of family stress and conflict on multiple aspects of children’s lives [66], and suggests that helping parents to develop better skills to support their child at home and school would improve children’s feelings of well-being.

References

Ben-Arieh A, et al. (2014) Multifaceted concept of child well-being, in handbook of child well-being. In: Theories, methods and policies in global perspective, Ben-Arieh A, et al. (eds.) Springer, Dordrecht

Bradshaw J et al (2013) Children’s subjective well-being in rich countries. Child Indic Res 6(4):619–635

Bradshaw J (2015) Subjective well-being and social policy: can nations make their children happier? Child Indic Res 8(1):227–241

Chanfreau J et al (2013) Predicting wellbeing. NatCen Social Research for the Department of Health, London

McAuley C, Layte R (2012) Exploring the relative influence of family stressors and socio-economic context on children’s happiness and well-being. Child Indic Res 5(3):523–545

Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA (1998) The ecology of developmental processes. In: Damon W, Lerner RM (eds.) Handbook of child psychology, Vol 1. Theoretical models of human development, 5th edn. John Wiley & Sons Inc, Hoboken, p 993–1028

Lamu AN, Olsen JA (2016) The relative importance of health, income and social relations for subjective well-being: an integrative analysis. Soc Sci Med 152:176–185

The Children’s Society (2013) The Good Childhood Report 2013. The Children’s Society and the University of York, York

Whitaker RC, Orzol SM, Kahn RS (2006) Maternal mental health, substance use, and domestic violence in the year after delivery and subsequent behavior problems in children at age 3 years. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63(5):551–560

Kiernan KE, Mensah FK (2009) Poverty, maternal depression, family status and children’s cognitive and behavioural development in early childhood: a longitudinal study. J Soc Policy 38:569–588

Bøe T et al (2014) Socioeconomic status and child mental health: the role of parental emotional well-being and parenting practices. J Abnorm Child Psychol 42(5):705–715

Ryan RM, Claessens A (2013) Associations between family structure changes and children’s behavior problems: the moderating effects of timing and marital birth. Dev Psychol 49(7):1219–1231

Powdthavee N, Vignoles A (2008) Mental health of parents and life satisfaction of children: a within-family analysis of intergenerational transmission of well-being. Soc Indic Res 88(3):397–422

Clair A (2012) The relationship between parent’s subjective well-being and the life satisfaction of their children in Britain. Child Indic Res 5(4):631–650

Uusitalo-Malmivaara L, Lehto JE (2013) Social factors explaining children’s subjective happiness and depressive symptoms. Soc Indic Res 111(2):603–615

Proctor CL, Linley PA, Maltby J (2009) Youth life satisfaction: a review of the literature. J Happiness Stud 10(5):583–630

Rees G, Pople L, Goswami H (2011) Understanding children’s well-being: links between family economic factors and children’s subjective well-being: initial findings from wave 2 and wave 3 quarterly surveys, The Children’s Society, London

Knies G (2012) Life satisfaction and material well-being of young people in the UK. In: ISER Working Paper 2012, University of Essex: Institute for Social and Economic Research, Colchester

Main G (2014) Child poverty and children’s subjective well-being. Child Indic Res 7(3):451–472

Zullig KJ et al (2005) Associations among family structure, demographics, and adolescent perceived life satisfaction. J Child Fam Stud 14(2):195–206

Levin KA, Dallago L, Currie C (2012) The association between adolescent life satisfaction, family structure, family affluence and gender differences in parent-child communication. Soc Indic Res 106(2):287–305

Bjarnason T et al (2012) Life satisfaction among children in different family structures: a comparative study of 36 Western Societies. Child Soc 26(1):51–62

Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J (2000) The neighborhoods they live in: the effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychol Bull 126(2):309–337

Midouhas E, Kuang Y, Flouri E (2014) Neighbourhood human capital and the development of children’s emotional and behavioural problems: the mediating role of parenting and schools. Health Place 27:155–161

Flouri E, Tzavidis N, Kallis C (2010) Area and family effects on the psychopathology of the Millennium Cohort Study children and their older siblings. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 51(2):152–161

Sheridan SM et al (2014) The influence of rurality and parental affect on kindergarten children’s social and behavioral functioning. Early Educ Dev 25(7):1057–1082

Midouhas E, Platt L (2014) Rural-urban area of residence and trajectories of children’s behavior in England. Health Place 30:226–233

Thompson MJJ et al (1996) Mental health of preschool children and their mothers in a mixed urban–rural population. 1. Prevalence and ecological factors. Br J Psychiatry 168(1):16–20

Lyneham HJ, Rapee RM (2007) Childhood anxiety in rural and urban areas: presentation, impact and help seeking. Aust J Psychol 59(2):108–118

Oberle E, Schonert-Reichl KA, Zumbo BD (2011) Life satisfaction in early adolescence: personal, neighborhood, school, family, and peer influences. J Youth Adolesc 40(7):889–901

Yeresyan I, Lohaus A (2014) Stress and wellbeing among Turkish and German adolescents living in rural and urban areas. Rural Remote Health 14 (3)

Levin K (2014) PP54 Urban–rural differences in adolescent mental health and wellbeing in Scotland. J Epidemiol Community Health 68(Suppl 1):A68–A69

Belsky J (1984) The determinants of parenting: a process model. Child Dev 55(1):83–96

Conger RD, Conger KJ, Martin MJ (2010) Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. J Marriage Family 72(3):685–704

Hood M, Conlon E, Andrews G (2008) Preschool home literacy practices and children’s literacy development: a longitudinal analysis. J Educ Psychol 100(2):252–271

Linver MR, Brooks-Gunn J, Kohen DE (2002) Family processes as pathways from income to young children’s development. Dev Psychol 38(5):719–734

Bradley RH, Corwyn RF (2002) Socioeconomic status and child development. Annu Rev Psychol 53(1):371

Rijlaarsdam J et al (2013) Economic disadvantage and young children’s emotional and behavioral problems: mechanisms of risk. J Abnorm Child Psychol 41(1):125–137

Kelly Y et al (2011) What role for the home learning environment and parenting in reducing the socioeconomic gradient in child development? Findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. Arch Dis Child 96(9):832–837

Kiernan KE, Huerta MC (2008) Economic deprivation, maternal depression, parenting and children’s cognitive and emotional development in early childhood. Br J Sociol 59(4):783–806

Zhang X (2014) Family income, parental education and internalizing and externalizing psychopathology among 2–3-year-old Chinese children: the mediator effect of parent-child conflict. Int J Psychol 49(1):30–37

Hur E, Buettner CK, Jeon L (2015) Parental depressive symptoms and children’s school-readiness: the indirect effect of household Chaos. J Child Fam Stud 24(11):3462–3473

Ostberg M, Hagekull B (2013) Parenting stress and external stressors as predictors of maternal ratings of child adjustment. Scand J Psychol 54(3):213–221

Odgers CL et al (2012) Supportive parenting mediates neighborhood socioeconomic disparities in children’s antisocial behavior from ages 5 to 12. Dev Psychopathol 24(3):705–721

Carver A, Timperio A, Crawford D (2008) Playing it safe: the influence of neighbourhood safety on children’s physical activity—a review. Health Place 14(2):217–227

Weir LA, Etelson D, Brand DA (2006) Parents’ perceptions of neighborhood safety and children’s physical activity. Prev Med 43(3):212–217

Halleröd B (2006) Sour grapes: relative deprivation, adaptive preferences and the measurement of poverty. J Soc Policy 35(03):371–390

Cummins RA (2010) Subjective wellbeing, homeostatically protected mood and depression: a synthesis. J Happiness Stud 11(1):1–17

Ridge T (2009) Living with poverty: a review of the literature on children’s and families’ experiences of poverty. In: Research Report No 594, Department for Work and Pensions, London

Eriksson U, Hochwalder J, Sellstrom E (2011) Perceptions of community trust and safety—consequences for children’s well-being in rural and urban contexts. Acta Paediatr 100(10):1373–1378

Gascon M et al (2015) Mental health benefits of long-term exposure to residential green and blue spaces: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12(4):4354–4379

Powell MA, Taylor N, Smith AB (2013) Constructions of rural childhood: challenging dominant perspectives. Child Geogr 11(1):117–131

Bourke L et al (2012) Understanding rural and remote health: a framework for analysis in Australia. Health Place 18(3):496–503

Kelly BJ et al (2011) Determinants of mental health and well-being within rural and remote communities. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46(12):1331–1342

Bradshaw P et al (2007) Growing Up in Scotland sweep 1–2005 user guide. Scottish Centre for Social Research, Edinburgh

Huebner ES, Alderman GL (1993) Convergent and discriminant validation of a children life satisfaction scale: its relationship to self-reported and teacher-reported psychological-problems and school functioning. Soc Indic Res 30(1):71–82

Huebner ES (1994) Preliminary development and validation of a multidimensional life satisfaction scale for children. Psychol Assess 6(2):149–158

Goodman R (2001) Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40(11):1337–1345

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998–2012) Mplus User’s Guide, 7th edn., Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles

Yap ST, Baharudin R (2016) The relationship between adolescents’ perceived parental involvement, self-efficacy beliefs, and subjective well-being: a multiple mediator model. Soc Indic Res 126(1):257–278

Abubakar A et al (2015) Perceptions of parenting styles and their associations with mental health and life satisfaction among urban Indonesian adolescents. J Child Fam Stud 24(9):2680–2692

Brumariu LE, Kerns KA (2010) Parent–child attachment and internalizing symptoms in childhood and adolescence: a review of empirical findings and future directions. Dev Psychopathol 22(1):177–203

Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE (2002) Risky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol Bull 128(2):330–366

Cuellar J, Jones DJ, Sterrett E (2015) Examining parenting in the neighborhood context: a review. J Child Fam Stud 24(1):195–219

Middleton N et al (2003) Urban–rural differences in suicide trends in young adults: England and Wales, 1981–1998. Soc Sci Med 57(7):1183–1194

Bronstein P et al (1998) Preventing middle school adjustment problems for children from lower-income families: a program for aware parenting. J Appl Dev Psychol 19(1):129–152

Acknowledgments

This research was Supported by Medical Research Council Grants MC_UU_12017/9, MC_UU_12017/3, MC_UU_12017/11 and MC_UU_12017/12. The Growing Up in Scotland study is funded by the Scottish Government. The funder had no part in: the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript. We thank Paul Bradshaw and the team at ScotCen Social Research for data collection, and we are grateful to the families who participated in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical standards

Each sweep of data collection was subject to medical ethical review by the Scotland ‘A’ MREC committee, in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. All parents interviewed gave their informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Parkes, A., Sweeting, H. & Wight, D. What shapes 7-year-olds’ subjective well-being? Prospective analysis of early childhood and parenting using the Growing Up in Scotland study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 51, 1417–1428 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1246-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1246-z