Abstract

Purpose

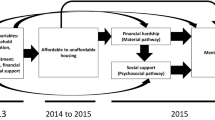

Poor mental health has been consistently linked with the experience of financial hardship and poverty. However, the temporal association between these factors must be clarified before hardship alleviation can be considered as an effective mental health promotion and prevention strategy. We examined whether the longitudinal associations between financial hardship and mental health problems are best explained by an individual’s current or prior experience of hardship, or their underlying vulnerability.

Methods

We analysed nine waves (years: 2001–2010) of nationally representative panel data from the Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey (n = 11,134). Two components of financial hardship (deprivation and cash-flow problems) and income poverty were coded into time-varying and time-invariant variables reflecting the contemporaneous experience of hardship (i.e., current), the prior experience of hardship (lagged/12 months), and any experience of hardship during the study period (vulnerability). Multilevel, mixed-effect logistic regression models tested the associations between these measures and mental health.

Results

Respondents who reported deprivation and cash-flow problems had greater risk of mental health problems than those who did not. Individuals vulnerable to hardship had greater risk of mental health problems, even at the times they did not report hardship. However, their risk of mental health problems was greater on occasions when they did experience hardship.

Conclusions

The results are consistent with the argument that economic and social programmes that address and prevent hardship may promote community mental health.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Chatterji S, Lee S, Ormel J, Ustun TB, Wang PS (2009) The global burden of mental disorders: an update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 18(1):23–33

Jacka FN, Mykletun A, Berk M (2012) Moving towards a population health approach to the primary prevention of common mental disorders. BMC Med 10:149

Munoz RF, Cuijpers P, Smit F, Barrera AZ, Leykin Y (2010) Prevention of major depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 6:181–212

Cuijpers P, Beekman AT, Reynolds CF 3rd (2012) Preventing depression: a global priority. JAMA 307(10):1033–1034

Smedley BD, Syme SL (2001) Promoting health: intervention strategies from social and behavioral research. Am J Health Promot 15(3):149–166

Jacka FN, Reavley NJ, Jorm AF, Toumbourou JW, Lewis AJ, Berk M (2013) Prevention of common mental disorders: what can we learn from those who have gone before and where do we go next? Aust N Z J Psychiatry 47(10):920–929

Marmot M, Ryff CD, Bumpass LL, Shipley M, Marks NF (1997) Social inequalities in health: next questions and converging evidence. Soc Sci Med 44(6):901–910

Fryers T, Melzer D, Jenkins R (2003) Social inequalities and the common mental disorders: a systematic review of the evidence. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 38(5):229–237

Lorant V, Deliège D, Eaton W, Robert A, Philippot P, Ansseau M (2003) Socioeconomic Inequalities in Depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 157(2):98–112

Krieger N (2007) Why Epidemiologists Cannot Afford to Ignore Poverty. Epidemiology 18(6):658–663

Lewis G, Bebbington P, Brugha T, Farrell M, Gill B, Jenkins R, Meltzer H (1998) Socioeconomic status, standard of living, and neurotic disorder. Lancet 352(9128):605–609

Whelan CT (1993) The role of social support in mediating the psychological consequences of economic stress. Sociol Health Illn 15(1):86–101

Whelan CT, Layte R, Maître B, Nolan B (2001) Income, Deprivation, and Economic Strain. An Analysis of the European Community Household Panel. Eur Sociol Rev 17(4):357–372

Ringen S (1988) Direct and Indirect Measures of Poverty. J Soc Policy 17(03):351–365

Saunders P, Adelman L (2006) Income poverty, deprivation and exclusion: a Comparative study of Australia and Britain. J Soc Policy 35(04):559–584

Heflin CM, Iceland J (2009) Poverty, material hardship, and depression. Soc Sci Q 90(5):1051–1071

Kahn JR, Pearlin LI (2006) Financial Strain over the Life Course and Health among Older Adults. J Health Soc Behav 47(1):17–31

Butterworth P, Olesen SC, Leach LS (2012) The role of hardship in the association between socio-economic position and depression. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 46(4):364–373

Butterworth P, Cherbuin N, Sachdev P, Anstey KJ (2012) The association between financial hardship and amygdala and hippocampal volumes: results from the PATH through life project. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 7(5):548–556

Lorant V, Croux C, Weich S, Deliege D, Mackenbach J, Ansseau M (2007) Depression and socio-economic risk factors: 7-year longitudinal population study. Br J Psychiatry 190(4):293–298

Ahnquist J, Wamala SP (2011) Economic hardships in adulthood and mental health in Sweden. the Swedish National Public Health Survey 2009. BMC Public Health 11:788

Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Shema SJ (1997) Cumulative Impact of Sustained Economic Hardship on Physical, Cognitive, Psychological, and Social Functioning. N Engl J Med 337(26):1889–1895

Saunders P (1998) Poverty and health: exploring the links between financial stress and emotional stress in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health 22(1):11–16

Saunders P, Zhu A (2009) Comparing Disadvantage and Well-being in Australian Families. Australian J Lab Econ 12(1):21–39

Mirowsky J, Ross CE (2001) Age and the Effect of Economic Hardship on Depression. J Health Soc Behav 42(2):132–150

Weich S, Lewis G (1998) Poverty, unemployment, and common mental disorders: population based cohort study. BMJ 317(7151):115–119

Butterworth P, Rodgers B, Windsor TD (2009) Financial hardship, socio-economic position and depression: results from the PATH Through Life Survey. Soc Sci Med 69(2):229–237

Weich S, Lewis G (1998) Material standard of living, social class, and the prevalence of the common mental disorders in Great Britain. J Epidemiol Community Health 52(1):8–14

Madianos M, Economou M, Alexiou T, Stefanis C (2011) Depression and economic hardship across Greece in 2008 and 2009: two cross-sectional surveys nationwide. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46(10):943–952

Lahelma E, Laaksonen M, Martikainen P, Rahkonen O, Sarlio-Lahteenkorva S (2006) Multiple measures of socioeconomic circumstances and common mental disorders. Soc Sci Med 63(5):1383–1399

Rogers B (1991) Socio-economic status, employment and neurosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 26(3):104–114

Suglia SF, Duarte C, Sternthal M, Enlow MB, Wright RJ (2009) Social and Physical Environmental Factors and Maternal Mental Health. Epidemiology 20(6):S180

Bray JR (2001) Hardship in Australia: an analysis of financial stress indicators in the 1998–99 Australian bureau of statistics household expenditure survey. FaHCSIA, Canberra

Butterworth P, Crosier T (2006) Deriving a measure of financial hardship from the HILDA Survey. Australian Social Policy 2005:1-Dec

Heflin CM, Siefert K, Williams DR (2005) Food insufficiency and women’s mental health: findings from a 3-year panel of welfare recipients. Soc Sci Med 61(9):1971–1982

Tsai AC, Bangsberg DR, Frongillo EA, Hunt PW, Muzoora C, Martin JN, Weiser SD (2012) Food insecurity, depression and the modifying role of social support among people living with HIV/AIDS in rural Uganda. Soc Sci Med 74(12):2012–2019

Skapinakis P (2007) Commentary: socioeconomic position and common mental disorders: what do we need to know? Int J Epidemiol 36(4):786–788

Skapinakis P, Weich S, Lewis G, Singleton N, Araya R (2006) Socio-economic position and common mental disorders: longitudinal study in the general population in the UK. Br J Psychiatry 189(2):109–117

Lorant V, Deliege D, Eaton W, Robert A, Philippot P, Ansseau M (2003) Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 157(2):98–112

Wooden M, Watson N (2007) The HILDA Survey and its Contribution to Economic and Social Research (So Far). Econ Rec 83(261):208–231

Ware JE Jr, Gandek B (1998) Overview of the SF-36 health survey and the international quality of life assessment (IQOLA) project. J Clin Epidemiol 51(11):903–912

Butterworth P, Crosier T (2004) The validity of the SF-36 in an Australian National Household Survey: demonstrating the applicability of the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey to examination of health inequalities. BMC Public Health 4:44

Rumpf HJ, Meyer C, Hapke U, John U (2001) Screening for mental health: validity of the MHI-5 using DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric disorders as gold standard. Psychiatry Res 105(3):243–253

Cuijpers P, Smits N, Donker T, ten Have M, de Graaf R (2009) Screening for mood and anxiety disorders with the five-item, the three-item, and the two-item mental health inventory. Psychiatry Res 168(3):250–255

Kelly M, Dunstan F, Lloyd K, Fone D (2008) Evaluating cutpoints for the MHI-5 and MCS using the GHQ-12: a comparison of five different methods. BMC Psychiatry 8(1):10

Rumpf HJ, Meyer C, Hapke U, John U (2001) Screening for mental health: validity of the MHI-5 using DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric disorders as gold standard. Psychiatry Res 105(3):243–253

Gill S, Butterworth P, Rodgers B, Anstey K, Villamil E, Melzer D (2006) Mental health and the timing of Men’s retirement. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 41(7):515–522

Kiely KM, Butterworth P (2013) Mental health selection and income support dynamics: multiple spell discrete-time survival analyses of welfare receipt. J Epidemiol Community Health 68(4):349–355

Kiely KM, Butterworth P (2013) The contribution of financial hardship, socioeconomic position and physical health to mental health problems among welfare recipients. Aust N Z J Public Health 37(6):589–590

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SL, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM (2002) Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 32(6):959–976

Slade T, Johnston A, Oakley Browne MA, Andrews G, Whiteford H (2009) 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: methods and key findings. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 43(7):594–605

Hagenaars A, de Vos K, Zaidi MA (1994) Poverty Statistics in the Late 1980s: Research Based on Micro-data. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxemburg

Curran PJ, Bauer DJ (2011) The Disaggregation of Within-Person and Between-Person Effects in Longitudinal Models of Change. Annu Rev Psychol 62(1):583–619

ABS (2008) Census of population and housing: socio-economic Indexes for area (SEIFA), Australia—data only. Common wealth of Australia, Canberra

Lynch JW, Davey Smith G, Kaplan GA, House JS (2000) Income inequality and mortality: importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment, or material conditions. BMJ 320:1200–1204

Marmot M, Wilkinson RG et al (2001) Psychosocial and material pathways in the relation between income and health: a response to Lynch. BMJ 322:1233–1236

Levecque K, Van Rossem R, De Boyser K, Van de Velde S, Bracke P (2011) Economic Hardship and Depression across the Life Course: the Impact of Welfare State Regimes. J Health Soc Behav 52(2):262–276

Patel V (2007) Mental health in low- and middle-income countries. Br Med Bull 81–82(1):81–96

Ozer EJ, Fernald LC, Weber A, Flynn EP, VanderWeele TJ (2011) Does alleviating poverty affect mothers’ depressive symptoms? A quasi-experimental investigation of Mexico’s Oportunidades programme. Int J Epidemiol 40(6):1565–1576

Costello E, Compton SN, Keeler G, Angold A (2003) Relationships between poverty and psychopathology: a natural experiment. JAMA 290(15):2023–2029

Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Copeland W, Angold A (2010) Association of family income supplements in adolescence with development of psychiatric and substance use disorders in adulthood among an American Indian population. JAMA 303(19):1954–1960

Fragar L, Kelly B, Peters M, Henderson A, Tonna A (2008) Partnerships to promote mental health of NSW farmers: the New South Wales Farmers Blueprint for Mental Health. Aust J Rural Health 16(3):170–175

Heflin CM, Ziliak JP (2008) Food insufficiency, food stamp participation, and mental health. Soc Sci Q 89(3):706–727

Acknowledgments

Kiely is funded by Alzheimer’s Australia Dementia Research Foundation (AADRF) Fellowship #DGP13F00005. Butterworth is funded by Australian Research Council (ARC) Future Fellowship #FT13101444. Olesen and Leach are funded by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Early Career Fellowships #1035690 and #1035803, respectively. This paper uses unit record data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. The HILDA Project was initiated and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (Melbourne Institute). The findings and views reported in this paper, however, are those of the author and should not be attributed to either FaHCSIA or the Melbourne Institute.

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

The HILDA survey was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Melbourne and is therefore in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. All respondents gave their informed consent prior to their participation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kiely, K.M., Leach, L.S., Olesen, S.C. et al. How financial hardship is associated with the onset of mental health problems over time. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50, 909–918 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1027-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1027-0