Abstract

Purpose

To examine the associations between family social support, community “social capital” and mental health and educational outcomes.

Methods

The data come from the Longitudinal Study of Young People in England, a multi-stage stratified nationally representative random sample. Family social support (parental relationships, evening meal with family, parental surveillance) and community social capital (parental involvement at school, sociability, involvement in activities outside the home) were measured at baseline (age 13–14), using a variety of instruments. Mental health was measured at age 14–15 (GHQ-12). Educational achievement was measured at age 15–16 by achievement at the General Certificate of Secondary Education.

Results

After adjustments, good paternal (OR = 0.70, 95% CI 0.56–0.86) and maternal (OR = 0.65, 95% CI 0.53–0.81) relationships, high parental surveillance (OR = 0.81, 95% CI 0.69–0.94) and frequency of evening meal with family (6 or 7 times a week: OR = 0.77, 95% CI 0.61–0.96) were associated with lower odds of poor mental health. A good paternal relationship (OR = 1.27, 95% CI 1.06–1.51), high parental surveillance (OR = 1.37, 95% CI 1.20–1.58), high frequency of evening meal with family (OR = 1.64, 95% CI 1.33–2.03) high involvement in extra-curricular activities (OR = 2.57, 95% CI 2.11–3.13) and parental involvement at school (OR = 1.60, 95% CI 1.37–1.87) were associated with higher odds of reaching the educational benchmark. Participating in non-directed activities was associated with lower odds of reaching the benchmark (OR = 0.79, 95% CI 0.70–0.89).

Conclusions

Building social capital in deprived communities may be one way in which both mental health and educational outcomes could be improved. In particular, there is a need to focus on the family as a provider of support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A variety of welfare outcomes for young people have been highlighted as being related to social capital, defined broadly as a type of “capital” resulting from the social relationships between people. These include physical health, mental health, life skills (including literacy and numeracy), perceptions of well-being and developmental stage for age [16]. This paper focuses on the association between social capital and psychological distress and educational achievement using the Longitudinal Study of Young People in England (LSYPE).

Several studies have found that social capital is associated with mental health outcomes in young people [17, 21, 24, 36, 43] as well as educational outcomes including achievement and staying on at school [4, 6, 13, 18, 22, 25, 26, 39, 40]. Few have compared and contrasted educational and mental health outcomes in relation to social capital. One study in the United States looked at four factors associated with the concept of social capital (peer behaviour, time spent without an adult, adolescent resources and parental behaviour) and their associations with psychological adjustment and grades; the results showed that negative peer behaviour was associated with poor well-being and that adolescent resources and parental behaviour had some compensatory effects on psychological adjustment and grades [41]. Another US study concluded that overall social capital had a role to play in helping youth to negotiate their way out of disadvantage but stressed the importance of treating social capital as a multidimensional concept [13]. The study found that high levels of social capital were more strongly associated with educational success (high school graduation and being enrolled in college) than robust mental health. As far as the authors are aware, no studies have compared and contrasted these two important well-being outcomes in the British context.

Defining and measuring social capital

A key challenge in any study of social capital is in defining the concept itself. The multitude of ways in which social capital has been operationalised has led to some debate over whether the term is even valid as a single conceptual entity [37].

We argue that it is possible to reach a theoretically informed definition of social capital suitable for testing empirically. We make four key points in the discussion of defining and measuring social capital that follows:

-

1.

Social capital is about relationships

-

2.

Social capital is best seen as a property of individuals

-

3.

Social capital is not a universal good and can have both positive and negative outcomes

-

4.

A strong theoretical grounding is needed to empirically test social capital. Here, Coleman’s conceptualisation is used. There are some modifications based on critiques which have emphasised the need for some agency to be attributed to young people rather than using parental social capital as a proxy [16, 27, 28].

Although the term has often been criticised for its conceptual ambiguity [10, 31, 38], there are some points on which the key players in the social capital debate agree. Most fundamentally, social capital concerns the relationships between people. Field [12] summed up the theory of social capital in two words: “relationships matter”. Bourdieu [3] defined social capital as “…membership in a group”. For Coleman [5], the first theorist to subject the concept to empirical testing social capital existed “in the relations between persons”. For Putnam [34], whose work was largely responsible for bringing the concept of social capital into the mainstream, social capital was made up of “connections between individuals”.

There are two main schools of thought within the social capital debate [1, 31]. The first, sociological, view sees social capital as a resource which creates benefits for individuals through their participation in groups. This line of thinking was given the most refined treatment by Bourdieu [3] and was later amplified by Coleman’s [5] elucidation of “family social capital” [1]. The second view sees social capital as a feature of communities such as towns, cities, states and nations; this view of social capital was introduced by political scientists who equate social capital with the level of “civicness” in a given area [32–34]. This is usually measured through membership in associations and participatory behaviour. We agree with Portes [31] that the most promise for social capital as a concept which can be empirically tested lies in the first approach. Whilst it seems reasonable to measure an individual’s stock of social capital, it is more problematic theoretically to use individual measures of social capital (such as associational membership) and from them derive aggregate quantities of social capital said to be available to entire communities (in some cases as large as nations). This paper will measure social capital at the individual level by looking at (1) relationships between children and their families and (2) at interactions between children, their families and the wider community, in line with Coleman’s [5] theoretical conceptualisation of social capital.

A further problem with many approaches to social capital is the tendency to see it as a universal good. Many commentators emphasise the need for some balance to be brought to the “frequent celebratory tone with which the concept is surrounded” [31]. Strong relationships can have a number of potentially negative outcomes as well as positive ones. Gang membership may often lead to high “bonding” social capital, for example [8]. In the context of health, a key mechanism through which social capital is said to impact on outcomes is through influencing health-related behaviours [20]. However, social participation can also have the opposite impact if those with which one spends most time are heavily involved in health-demoting pursuits [1]. This paper will show that social capital can have both negative and positive effects. By looking at two different outcomes (educational achievement and mental health), it will also demonstrate that the same type of social capital may work in different directions depending on the outcome in question.

Coleman argued that there were two main ways in which social capital could be developed. The first was through the family. Social capital, in the form of relationships within families, was argued to set the context within which parents’ financial and human capital could impact on the decisions made by children within education. High levels of social capital in the form of the physical presence of parents and a high level of attention to their children was seen as the only way in which parents could transmit their human capital to their children. We argue that this aspect of social capital may be more appropriately termed “family social support”.

This first dimension of Coleman’s theory has typically been operationalised by looking at (a) family structure (physical presence of two parents), (b) quality of child-parent relationships, (c) adult’s interest in the child, (d) monitoring of the child’s activities and, in a minority of studies, (e) extended family exchange and support [11]. In this paper, we examine the relationship between (b) quality of child–parent relationships, (c) adult’s interest in the child and (d) monitoring of the child’s activities and mental health and educational outcomes.

The second way in which social capital could be important, according to Coleman, was through adults in the community sanctioning their children’s behaviour. Coleman argued that a student is more likely to conform if sanctions against undesirable behaviour are communicated to them through strong network ties involving the parents of the student’s friends and friends of the family. There are many ways in which strong parental networks might impact on educational outcomes. If parents know each other and regularly see each other, deviant behaviour such as truancy can be more easily detected (if a student lies to their parents they are more easily found out), parents are more likely to find out about bad behaviour within the school and, finally, they are able to determine whether their children’s peers have similar aspirations to those that they hold for their children [4]. Qualitative work has supported Coleman’s differentiation between home-based “social support” and community based social capital [16] and this distinction will be maintained here.

Coleman has been criticised for his “top-down” approach, which focuses on parents’ social networks at the expense of the relationships between young people themselves [16, 23, 27]. In a review, Morrow [27] argues that there is also a need to look at friends, social networks and activities within the community undertaken by adolescents. As well as examining the impact of parents’ social networks therefore, as far as possible with the measures available, this paper will examine the impact of adolescents’ relationships with their friends and the social activities that they undertake (both formal and informal). The data available give us the ability to look at a number of dimensions of adolescents’ social lives. These include time spent with friends and time spent engaging in three types of activities outside the home: non-directed activity (or “hanging about”), extra-curricular activities and community activities. This is of particular interest in the context of the social capital debate, as some theorists (notably Bourdieu [3] and Putnam [34]) have argued for “community activities” such as going to political meetings or organisations like the scouts or guides as forms of “bridging” social capital between or into the middle classes that are more likely to result in returns for the individual.

Aims

This paper will prospectively examine the associations between family social support, community social capital and two outcomes: mental health and educational achievement. We hypothesise that:

-

1.

Both family social support and community social capital will be associated with mental health and educational outcomes.

-

2.

The direction of association will vary; some elements of social capital will have a positive impact on outcomes whilst others will have a negative impact.

-

3.

Associations will be attenuated after adjustment for the confounding variables of gender, parental social class and ethnicity.

Methods

Data

The dataset used was the Longitudinal Study of Young People in England (LSYPE), commissioned by the Department for Children, Schools and Families [7]. The sampling procedure was a multi-stage stratified random sample, which was intended to be nationally representative. 15,770 households were in the first wave of the study (13,539 households at Wave 2). The study began in 2004, when the sample was aged between 13 and 14 years old. Interviews were carried out with the same sample annually to obtain information from the young person and additional information from a main and second parent interview. Data were collected by face-to-face interviews with some self-completion sections. The data were supplemented by linkage to administrative records such as the National Pupil Database (NPD) from which information on educational attainment was available.

Measures

Mental health

Mental health was measured using the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) [15] at wave 2 (age 14–15). This screens for anxiety and depression. A score of 4 or greater was taken as a “case”. The 12-item GHQ has been shown to have high reliability [2, 30] and reasonable sensitivity and specificity [9, 14, 19].

Educational attainment

The measure used was the attainment of 5 or more A*–C grades at the General Certificate of Education (GCSE) including English and mathematics. These are national examinations taken at age 16 by almost the entire cohort and this benchmark is the nationally accepted one.

Social support and social capital measures

Associations between the main outcome variables are measured in relation to family social support and community social capital (as held by the individual). These variables are categorised as follows:

-

1.

Family social support

-

a.

Quality of parent–child relationships/adult’s interest in the adolescent

-

b.

Monitoring of adolescent’s activities (parental surveillance)

-

a.

-

2.

Community social capital

-

a.

Parental social networks

-

b.

Adolescent’s sociability

-

c.

Adolescent’s involvement in activities outside the home

-

a.

The measures described below were all taken in wave 1 of the survey (age 13–14).

Quality of parent–child relationships/adult’s interest in the child

The following items were used to create a measure of the quality of the adolescents’ relationship with their parents: how well get on with (step-)mother, how well get on with (step-)father, how often fall out with (step-)mother, how often fall out with (step-)father, how often talk to (step-)mother about things that matter to young person, how often talk to (step-) father about things that matter to young person, how true it is to say (step-) mother likes young person to make own decisions, how true it is to say (step-)father likes young person to make own decisions. A scale was created from these items whereby the most positive answers were scored most highly, for example, in response to the first item “very well” scored 5, “fairly well” scored 4, “fairly badly” scored 3, “very badly” scored 2 and “I don’t see her” scored 1. These scores were summed to produce an overall total and then split into tertiles using the egen command in Stata.

An additional item on family relationships—how many times eaten evening meal with family in last 7 days was also examined. This item was coded into the categories: not at all, once or twice a week, 3–5 times a week, 6 or 7 times a week.

Parental surveillance

The following group of variables was used to measure parental surveillance: how often parents know where going out in evening, whether parents ever set curfew on school nights. A scale was created from these items whereby the most positive answers were scored most highly, for example in response to the first item “always” scored 5, “usually” scored 4, “sometimes” scored 3, “rarely” scored 2 and “never” scored 1. These scores were summed to produce an overall total and then split into tertiles using the egen command in Stata.

Parental social networks

Since the emphasis in Coleman’s work is on how parents can use their networks to monitor their children more closely, parental social networks were measured through looking at involvement with their child’s school.

Parental involvement in school: activities they or their partner get involved in at young person’s school: help out in class; help out elsewhere e.g. library, school trips, dinner duty; help out with fundraising activities; help out with special interest groups like sports, drama; get involved in parents and teachers associations; help with teacher assessments; school, parent governor; hosted an exchange student; donations, financial support to school; employed at school; attend events at school; other. If parents took part in one of the activities this variable was coded yes, otherwise no.

Adolescent’s sociability

Sociability was measured by two items: How many times young person had friends round to house in last 7 days and how many times young person gone out with friends in last 7 days. A scale was created from these items whereby the most positive answers were scored most highly, for example, in response to the first item “6 times or more” scored 4, “3–5 times” scored 3, “once or twice” scored 2 and “none” scored 1. These scores were summed to produce an overall total and then split into tertiles using the egen command in Stata.

Adolescent’s involvement in activities outside the home

Activities were split into three main groups, extra-curricular activities, community activities and non-directed activity as follows:

Extra-curricular activities Whether been to or done in last 4 weeks: played snooker, darts or pool; took part in any kind of sport; gone to see a football match or other sports event; gone to an amusement arcade; gone to a party, dance, nightclub or disco; gone to a pub or bar; gone to a cinema, theatre or concert; played a musical instrument. The number of activities engaged in was calculated and the total split into tertiles using the egen command in Stata.

Community activities Whether been to or done in last 4 weeks: gone to a political meeting, march, rally or demonstration; done community work; gone to a youth club or something like it (including scouts or girl guides). If one of these activities had been undertaken this variable was coded yes, otherwise no.

Non-directed activity Whether been to or done in last 4 weeks: just hung around, messed about near to your home; just hung about, messed about in the high street or the town, city centre. If one of these activities had been undertaken this variable was coded yes, otherwise no.

Parental social class

The social class measure used is the National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (NS-SEC). The social class background of the child was determined by the parent (either mother or father) who had the job which fell into the higher social class category (known as the dominance method). Work looking at the measurement of adolescent social class has indicated that it is optimal to take the social class of the mother into account either using this method or a “combined” social class measure [35].

Ethnicity

The following ethnic groups are identified (self-completion): white, mixed, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, black Caribbean, black African, other.

Data management

All data management and analysis was carried out using Stata version 10.0.

Statistical analysis

It was necessary to make adjustments for the clustered survey design in the analyses (using the svy commands in Stata). Data were reweighted to adjust for unequal probabilities of selection (except for in the descriptive analysis where no adjustments were made).

In the univariable analysis, crude odds ratios (ORs) were calculated using logistic regression for the association between (1) social capital variables and psychological distress (GHQ) and (2) social capital variables and educational achievement at age 16 (GCSE). Mantel–Haenszel methods and logistic regression were used to test for gender interactions. In cases where a gender interaction was found, stratum specific odds ratios are reported. Multivariable analysis was carried out using logistic regression. Social capital variables that were significant in the univariable analyses were entered into the multivariable models. The analyses were adjusted for gender, parental social class and ethnicity. The Wald test was used (testparm command in Stata) to assess goodness-of-fit.

Results

The unweighted descriptive statistics are reported in Table 1. About half of the sample was male (50.9%) and 33% of non-white ethnicity. A small percentage of parents had a degree level qualification (9.9% of mothers and 14.1% of fathers). A larger proportion had no qualification at all (27.5% of mothers and 26.4% of fathers). The proportion achieving 5 or more A*–C grades at GCSE was 45.9%. 18.1% of respondents scored high enough on the GHQ to be considered a “case”.

Descriptive statistics of the social support and social capital measures (not shown) indicated that almost half of the respondents had a family evening meal almost every day (43.8%). About 15% of parents were involved in at least one activity at their child’s school. A relatively small proportion of adolescents (23.7%) engaged in “community” activities such as voluntary work, youth clubs, scouts or guides. In contrast, a large proportion of the young people engaged in some sort of non-directed activity (“hanging about”): 59.8%.

Univariable analysis: background variables

Table 2 shows the univariable analysis for the association between background variables and mental health and educational achievement.

Girls had more than twice the odds of being a case on the GHQ compared to boys (OR = 2.49, 95% CI 2.23–2.77). They also had higher odds of achieving the educational benchmark (OR = 1.34, 95% CI 1.21–1.48).

Overall, parental social class had a stronger association with educational achievement than with mental health. The odds of a child of a routine worker achieving 5 or more A*–C grades at GCSE were just 8% of those of a child of a higher professional or manager. Differentials by parental social class were quite high even towards the top of the social spectrum. The odds of a pupil from a lower professional or managerial background achieving the benchmark at GCSE were less than half those of a pupil from a higher professional or managerial background. Parental social class was not associated with being a case on the GHQ. Very few minority ethnic groups had higher odds of being a case on the GHQ, compared to whites. There was some evidence for a difference for the mixed and ‘other’ groups, with respondents of mixed ethnic background having about one and a half times the odds of caseness (OR = 1.48, 95% CI 1.18–1.85) and the ‘other’ group having nearly twice the odds of caseness (OR = 1.83, 95% CI 1.32–2.53). Respondents of Indian ethnicity had higher odds of achieving the educational benchmark (OR = 1.70, 95% CI 1.40–2.06) compared to whites. Pakistani, Bangladeshi and black Caribbean respondents had lower odds of achieving 5 or more A*–C grades at GCSE, with black Caribbean respondents having the lowest odds: about half those of the white group (OR = 0.51, 95% CI 0.41–0.65).

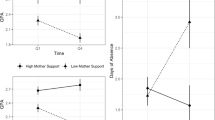

Gender interactions

Tests for homogeneity of odds ratios indicated a possible gender interaction for GHQ and relationship with mother (p = 0.0008), GHQ and sociability (p = 0.0001), GCSE achievement and extra-curricular activities (p = 0.0290) and GCSE achievement and parental surveillance (p = 0.0467). For these items, the regression analysis that follows was stratified by sex.

Univariable analysis: family social support and community “social capital”

Table 3 shows the univariable analysis for the relationship between “social capital” possessed and mental health and educational outcomes. Parental relationships were associated with mental health outcomes. Young people who had a good relationship with their father had about half the odds of being a case compared to those with a bad paternal relationship (OR = 0.47, 95% CI 0.40–0.56). There was evidence for effect modification by gender for maternal relationships, with a good maternal relationship being relatively more important for girls. Girls with a good maternal relationship had less than half the odds of being a case on the GHQ compared with girls with a poor maternal relationship (OR = 0.44, 95% CI 0.37–0.52). Boys with a good maternal relationship had about a third lower odds of being a case on the GHQ (OR = 0.63, 95% CI 0.49–0.80). Having an evening meal once or twice a week reduced the odds of being a case on the GHQ by about a third (OR = 0.66, 95% CI 0.54–0.81). Interestingly, greater frequency of having a family evening meal did not appear to further decrease the odds of psychological distress beyond this. Parental surveillance also had a positive impact on mental health; adolescents whose parents scored “high” on this measure were 16% less likely to be a case on the GHQ (OR = 0.84, 95% CI 0.74–0.95). Highly sociable boys had lower odds of psychological distress (OR = 0.64, 95% CI 0.49–0.84). This association was not apparent for girls. There was a significant association between non-directed activity (“hanging about”) and being a case on the GHQ. Pupils that had “just hung around” in the last 4 weeks had about 13% higher odds of being a case on the GHQ (OR = 1.13, 95% CI 1.01–1.26).

Poor parental relationships had a negative association with attainment. One of the most striking associations was that between GCSE attainment and having a family evening meal. The odds of achieving the benchmark at GCSE increased incrementally with frequency of eating together as a family. For those that had a family evening meal 6 or 7 times a week the odds of achieving the GCSE benchmark were more than twice those for pupils who did not have a family evening meal at all (OR = 2.23, 95% CI 1.91–2.61). Higher levels of parental surveillance had a positive impact on GCSE attainment. Adolescents with “high” levels of surveillance had nearly twice the odds of reaching the benchmark compared to those with low levels (boys OR = 1.80, 95% CI 1.57–2.05; girls OR = 1.80, 95% CI 1.56–2.08). Highly sociable adolescents had lower odds of reaching the benchmark compared to the least sociable (OR = 0.53, 95% CI 0.47–0.61), but moderately sociable adolescents had higher odds of reaching the benchmark compared to the least sociable (OR = 1.16, 95% CI 1.03–1.31). As with the GHQ, non-directed activity was associated with poorer outcomes. Respondents who had “just hung around” in the last 4 weeks had 30% lower odds of gaining the benchmark at GCSE (OR = 0.70, 95% CI 0.65–0.77).

There were a few of the social capital variables that did not impact on mental health but did appear to be associated with educational attainment. Parental involvement at school was associated with educational attainment. Pupils with parents who engaged in at least one activity at their school had about two and a half times the odds of achieving the benchmark compared to pupils whose parents did not engage in any activity (OR = 2.48, 95% CI 2.18–2.82). In addition, the lower the number of extra-curricular activities an individual was involved in, the higher the odds of them achieving the GCSE benchmark.

Multivariable analysis: GHQ

Table 4 shows the multivariable analysis with GHQ as the main outcome. The final model adjusted for gender and ethnicity (entering parental social class as a confounder did not improve the model). In the fully adjusted model for mental health, relationship with father remained a strong predictor of caseness. Respondents with a good paternal relationship had about a third lower odds of being a case on the GHQ compared to those with a poor paternal relationship (OR = 0.70, 95% CI 0.56–0.86). Those with a good maternal relationship had similarly lower odds of poor mental health (OR = 0.65, 95% CI 0.53–0.81). Parental surveillance was also positively associated with good mental health. If surveillance was moderate or high, compared to low, the odds of being a case on the GHQ were about 20% lower (high: OR = 0.81, 95% CI 0.69–0.94; moderate: OR = 0.79, 95% CI 0.66–0.95). Finally, having a family evening meal remained a predictor after all adjustments. The odds of being a case on the GHQ were reduced by approximately a quarter for respondents who had an evening meal with their family more than three times per week, compared to not at all (3–5 times a week: OR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.59–0.98). No community social capital variables were associated with the mental health outcome in the multivariable analysis.

Multivariable analysis: GCSE

Table 5 shows the multivariable analysis with GCSE attainment as the main outcome. The final model adjusted for gender, parental social class and ethnicity. A good paternal, but not maternal, relationship remained associated with the educational outcome. The odds of a respondent with a good paternal relationship reaching the benchmark were higher than for those with a poor paternal relationship (OR = 1.27, 95% CI 1.06–1.51). A high (but not moderate) level of parental surveillance was associated with high achievement; those who reported a high level of parental surveillance had nearly one and a half times the odds of reaching the benchmark compared to those with low parental surveillance (OR = 1.37, 95% CI 1.20–1.58). Having a family evening meal was associated with educational achievement in the multivariable analysis. Those that had an evening meal with their parents at least once or twice a week had about a third higher odds of reaching the benchmark (OR = 1.36, 95% CI 1.09–1.70) and the odds increased further for those having an evening meal three to five times a week, compared to none (OR = 1.76, 95% CI 1.40–2.22).

Some of the community social capital variables remained associated with educational achievement in the multivariable analysis. A high (but not moderate) level of sociability reduced the odds of reaching the benchmark by half (OR = 0.51, 95% CI 0.43–0.61). Respondents whose parents were involved in activities at their school had more than one and a half times the odds of reaching the academic benchmark compared to those whose parents were not involved (OR = 1.60, 95% CI 1.37–1.87). Participating in non-directed activity was negatively associated with reaching the benchmark (OR = 0.79, 95% CI 0.70–0.89) whilst engaging in extra-curricular activities had a positive impact on the odds of reaching the benchmark, with those in the highest tertile having more than two and a half times the odds of reaching the academic benchmark compared to those in the lowest tertile (OR = 2.57, 95% CI 2.11–3.13).

Discussion and conclusion

Main findings

This paper found that a number of dimensions of family social support and community “social capital” were associated with mental health and educational achievement in adolescence. In the case of mental health, family social support was particularly pertinent. After adjustments, having a poor relationship with one’s parents was associated with higher odds of being a case on the GHQ. Having an evening meal at least three times a week as a family reduced the odds of being a case on the GHQ by about a quarter. Parental surveillance was also associated with better mental health. Adjusting for parental social class did not attenuate the results, suggesting that the impact of positive parental support cannot be explained by social background. Community social capital seemed less important; no elements of community social capital were associated with poor mental health.

After adjustments, a poor paternal (though not maternal) relationship reduced the odds of reaching the GCSE benchmark. Eating as a family was also associated with achievement. A high level of parental surveillance increased the odds of achieving the benchmark. Community social capital was also important in the case of educational achievement. After adjustments, involvement in extra-curricular activities increased the odds of high achievement whilst non-directed activity (or “hanging about”) decreased the odds of achieving the benchmark. Whilst moderate levels of sociability had no impact on achievement, very high levels decreased the odds of achieving the benchmark by about half. Parental involvement with school was also associated with higher odds of achieving the academic benchmark at GCSE. Although parental social class explained some of the advantage conferred by high social capital, the association remained after full adjustments.

Community activities (akin to those highlighted by Putnam as predictors of the social capital of a community), such as participation in a political event, community work or scouts or guides were not associated with either outcome in the analysis.

Previous studies

This study echoes previous studies in finding that social capital is a multi-dimensional concept; whilst some aspects of social capital impacted positively and significantly on adolescent outcomes others had little or no impact. Israel et al. [18] found that process and structural aspects of family social capital related to educational outcomes and that process and structural aspects of community social capital, although they also helped adolescents to excel, contributed less strongly. Lauglo [22] found that strong family ties promoted achievement whilst friendship ties did not. McCulloch and Joshi [25] found that family level measures were much more salient in predicting measured cognitive ability in the British National Child Development Study than neighbourhood level conditions. The findings of this study mirror those of Furstenberg and Hughes [13] who found that whilst a large number of their measures of socioeconomic achievement (completion of high school, enrolment in college, global socioeconomic status) were significantly associated with their measures of social capital, mental health was associated with fewer social capital measures. In our case, mental health outcomes were most strongly associated with family social support, whilst for educational outcomes both family social support and community social capital were of importance. The development of social capital theory was most strongly rooted in educational research; this may partly explain why it applies less well to health outcomes than to educational ones.

Similarly, other studies have found that various elements of social capital can operate in different directions. For example, Lauglo’s [22] study of immigrants in Sweden suggests that whilst strong family ties are advantageous in promoting educational achievement, strong friendship ties are not; often the most culturally remote students were at an advantage in this respect. The way in which different elements of social capital relate to the two outcomes calls into question whether it can really be seen as a unitary concept. There are also instances in which high levels of sociability can have a negative impact, supporting a number of commentators’ assertions that social capital should not be seen as a “universal good” [10, 31]. Indeed, we found that the most sociable adolescents were less likely to achieve the GCSE benchmark. One way of moving forward with the social capital debate might be to recognise that these components of social capital can be differently linked to various outcomes.

The relatively small numbers of young people undertaking community activities (such as voluntary work and political activities) and the lack of association that this has with well-being outcomes supports Morrow’s [27, 28] assertion that this conceptualisation of social capital is not so relevant to young people, at least in Britain. It tends to contradict Bourdieu and Putnam’s assertion that such activities may lead to opportunities for individuals to make use of bridging social capital. However, using the LSYPE data we are unable to disaggregate these community activities or to test whether they really do create opportunities for “bridging” social capital. It may be that if specific activities were examined (for example girl guides and scouts) we might find more evidence for a positive association between community activities and educational outcomes. A further point concerns geography; in the United States, with its higher levels of religiosity and associational membership, Putnam’s operationalisation of social capital may be more effective as an explanation for observed outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

This is a large, nationally representative survey of young people, with more comprehensive measures of social capital than are available in most British surveys. The longitudinal design is a further strength; with cross-sectional data it would be difficult to establish whether social capital was a predictor of mental health and educational outcomes as the association could just as easily work in the opposite direction.

A key difficulty in the social capital literature is that there are few accepted and validated measures of the concept. This paper has sought to arrive at a theoretically informed framework to test social capital empirically, but it is possible that some of the measures do not capture the concept adequately. For example, although the study contains a measure of adolescent sociability (as measured by the amount of time that the young person spends at their friends houses and vice versa), there is no measure available for looking at the quality of these relationships. Within the activity measures, there is no indication of whether these are done with other young people or not. Parental involvement at school may not be a sufficient proxy for parental social networks that are able to apply sanctions in the case of deviant behaviour in Coleman’s sense. There are a number of other ways in which parents might interact with other adults to achieve this end, for example through neighbourhood associations or religious groups.

The measure for mental health could also be improved; the GHQ provides a very general measure of psychological distress and although it has high reliability and satisfactory sensitivity and specificity, its factor structure remains under debate [42].

Future research

In order to increase the comparability of work looking at different outcomes in varying contexts, it may be helpful to encourage survey development using more consistent measures, such as that developed by Onyx and Bullen [29], which measures eight specific factors. As noted above, however, these factors may be linked differently to different outcomes and simply summing the scale into an overall total of “social capital” may mask important variations.

Conclusions and implications

Through empirically testing a theoretically informed model of social capital, this paper suggests that there are important ways in which the family, in particular, can influence mental health and educational outcomes. Although parental social class has a strong impact on outcomes, particularly educational achievement, it does not entirely explain the strong associations observed between many dimensions of family social support and the outcomes explored here. This implies that promoting family social support and building community social capital in more deprived communities may be one way in which both mental health and educational outcomes could be improved. In particular, our research suggests that there is a need to focus on the family as a provider of support to young people and to ensure that workplaces are able to provide flexible working patterns in order to allow parents to spend time with their children.

References

Almedom A (2005) Social capital and mental health: an interdisciplinary review of primary evidence. Soc Sci Med 61:943–964

Banks M, Clegg C, Jackson P, Kemp N, Stafford E, Wall T (1980) The use of the general health questionnaire as an indicator of mental health in occupational studies. J Occup Psychol 53:187–194

Bourdieu P (1997) The forms of capital. In: Halsey A, Lauder H, Brown P, Stuart Wells A (eds) Education: culture, economy, society. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 46–58

Carbonaro W (1998) A little help from my friend’s parents: intergenerational closure and educational outcomes. Sociol Educ 71:295–313

Coleman J (1988) Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol 94(Suppl):S95–S120

Coleman J, Hoffer T (1987) Public and private schools. Basic Books, New York

DCSF and National Centre for Social Research (2009) Longitudinal study of young people in England: waves one to four, 2004–2007 (computer file), 7th Edn. SN: 5545. UK Data Archive [distributor], Colchester, Essex

Deuchar R, Holligan C (2010) Gangs, sectarianism and social capital: a qualitative study of young people in Scotland. Sociology 44:13–30

Donath S (2001) The validity of the 12-item general health questionnaire in Australia: a comparison between three scoring methods. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 35:231–235

Durlauf S (1999) The case “against” social capital. Focus 20:1–5

Ferguson K (2006) Social capital and children’s wellbeing: a critical synthesis of the international social capital literature. Int JSoc Welf 15:2–18

Field J (2003) Social capital. Routledge, London

Furstenberg F, Hughes M (1995) Social capital and successful development among at-risk youth. J Marriage Fam 57:580–592

Goldberg D (1992) General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12). NFER-Nelson, Windsor

Goldberg D, Gater R, Sartorius N, Ustin T, Piccinelli M, Gueje O, Rutter C (1997) The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol Med 27:191–197

Harpham T (2003) Measuring the social capital of children. Young Lives Working Paper No 4, London Southbank University, London

Harpham T, Grant E, Rodriguez C (2004) Mental health and social capital in Cali, Colombia. Soc Sci Med 58:2267–2277

Israel G, Beaulieu L, Hartless G (2001) The influence of family and community social capital on educational achievement. Rural Sociol 66:43–68

Jacob K, Bhugra D, Mann A (1997) The validation of the 12-item general health questionnaire among ethnic Indian women living in the United Kingdom. Psychol Med 27:1215–1217

Kawachi I, Berkmann L (2000) Social cohesion, social capital and health. In: Berkmann L, Kawachi I (eds) Social epidemiology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 174–190

Klineberg E, Clark C, Bhui K, Haines M, Viner R, Head J, Woodley-Jones D, Stansfeld S (2006) Social support, ethnicity and mental health in adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 41:755–760

Lauglo J (2000) Social capital trumping class and cultural capital? Engagement with school among immigrant youth. In: Baron S, Field J, Schuller T (eds) Social capital: critical perspectives. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 142–167

Leonard M (2005) Children, childhood and social capital: exploring the links. Sociology 39:605–622

Linden J, Drukker M, Gunther N, Feron F, Os J (2003) Children’s mental health service use, neighbourhood socioeconomic deprivation, and social capital. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 38:507–514

McCulloch A, Joshi H (2001) Neighbourhood and family influences on the cognitive ability of children in the British National Child Development Study. Soc Sci Med 53:579–591

McNeal R (1999) Parental involvement as social capital: differential effectiveness on science achievement, truancy, and dropping out. Soc Forc 78:117–144

Morrow V (1999) Conceptualising social capital in relation to the well-being of children and young people: a critical review. Sociol Rev 47:744–765

Morrow V (2001) Young people’s explanations and experiences of social exclusion: retrieving Bourdieu’s concept of social capital. Int J Sociol Soc Policy 21:37–63

Onyx J, Bullen P (2000) Measuring social capital in five communities. J Appl Behav Sci 36:23–42

Politi P, Piccinelli M, Wilkinson G (1994) Reliability, validity and factor structure of the 12-item general health questionnaire among young males in Italy. Acta Psychiatr Scand 90:432–437

Portes A (1998) Social capital: its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annu Rev Sociol 24:1–24

Putnam R (1993) Making democracy work. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Putnam R (1995) Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. J Democr 61:65–78

Putnam R (2000) Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster, New York

Rothon C (2008) Women, men and social class revisited: an assessment of the utility of a “combined” schema in the context of minority ethnic educational achievement in Britain. Sociology 42:695–712

Runyan D, Hunter W, Socolar R, Amaya-Jackson L, English D, Landsverk J, Dubowitz H, Browne D, Bangdiwala S, Mathew R (1998) Children who prosper in unfavorable environments: the relationship to social capital. Pediatrics 101:12–18

Schuller T, Baron S, Field J (2000) Social capital: a review and critique. In: Baron S, Field J, Schuller T (eds) Social capital: critical perspectives. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 1–38

Sobel J (2002) Can we trust social capital. J Econ Lit 40:139–154

Sun Y (1999) The contextual effects of community social capital on academic performance. Soc Sci Res 28:403–426

Teachman J, Paasch K, Carver K (1997) Social capital and dropping out of school early. Soc Forc 75:1343–1359

Voydanoff P, Donnelly B (1999) Risk and protective factors for psychological adjustment and grades among adolescents. J Fam Issues 20:328–349

Ye S (2009) Factor structure of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12): the role of wording effects. Personal Individ Differ 46:197–201

Ziersch A, Baum F, MacDougall C, Putland C (2005) Neighbourhood life and social capital: the implications for health. Soc Sci Med 60:71–86

Acknowledgments

CR is funded by a Medical Research Council Special Training Fellowship (G0601707).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Rothon, C., Goodwin, L. & Stansfeld, S. Family social support, community “social capital” and adolescents’ mental health and educational outcomes: a longitudinal study in England. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47, 697–709 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0391-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0391-7