Abstract

Background

Little is known about the prevalence of clinically significant postpartum depression in women of varying social status. The purpose of the present study was to examine the prevalence of postpartum depression as a function of three indices of social status: income, education and occupational prestige.

Method

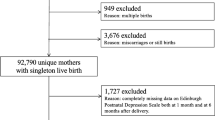

A sample of 4,332 postpartum women completed a demographic interview and the Inventory to Diagnose Depression, a self-report scale developed to identify a major depressive episode in accordance with DSM diagnostic criteria. Logistic regression was used to assess the relative significance of the three social status variables as risk factors for postpartum depression controlling for the effects of correlated demographic variables.

Results

In the logistic regression, income, occupational prestige, marital status, and number of children were significant predictors of postpartum depression controlling for the effects of other related demographic characteristics. The Wald Chi Square value for each of these significant predictors indicates that income was the strongest predictor.

Conclusions

The prevalence of postpartum depression was significantly higher in financially poor relative to financially affluent women. Maternal depression screening programs targeting women who are financially poor are well placed. Future research is needed to replicate the present findings in a more ethnically diverse sample that includes the full age range of teenage mothers.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

American Psychiatric Association Committee on Nomenclature and Statistics (1980) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 3rd edn. Author, Washington, DC

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, DSM-IV-TR, 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Arlington, Virginia

Beck CT (2001) Predictors of postpartum depression: an update. Nurs Res 50:275–285

Belle D, Doucet J (2003) Poverty, inequality, and discrimination as sources of depression among U.S. women. Psychol Women Quart 27:101–113

Brown GW, Moran PM (1997) Single mothers, poverty and depression. Psychol Med 27:21–33

Dearing E, Taylor BA, McCartney K (2004) Implications of family income dynamics for women’s depressive symptoms during the first 3 years after childbirth. Am J Public Health 94:1372–1377

Diener E, Biswas-Diener R (2002) Will money increase subjective well-being? Soc Indic Res 57:119–169

Dohrenwend BP, Dohrenwend BS (1969) Social status and psychological disorder: A causal inquiry. John Wiley, New York

Dohrenwend BP, Schwartz S (1995) Socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 8:138–141

Evans GW, English K (2002) The environment of poverty: multiple stressor exposure, psychophysiological stress, and socioemotional adjustment. Child Dev 73:1238–1248

Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T (2005) Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol 106:1071–1083

Goldston DB, O’Hara MW, Schartz HA (1990) Reliability, validity, and preliminary normative data for the inventory to diagnose depression in a college population. Psychol Assessment 2:212–215

Gross KH, Wells CS, Radigan-Garcia A, Dietz PM (2002) Correlates of self-reports of being very depressed in the months after delivery: results from the pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system. Matern Child Health J 6:247–253

Hobfoll SE, Ritter C, Lavin J, Hulsizer MR, Cameron RP (1995) Depression prevalence and incidence among inner-city pregnant and postpartum women. J Consult Clin Psychol 63:445–453

Hollingshead AB (1975) Four factor index of social status. New Haven, CT

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S (2000) Applied logistic regression. John Wiley & Sons, New York

Howell EA, Mora PA, Horowitz CR, Leventhal H (2005) Racial and ethnic differences in factors associated with early postpartum depressive symptoms. Obstet Gynecol 105:1442–1450

WHO International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology (2000) Cross-national comparisons of the prevalences and correlates of mental disorders. Bull World Health Organ 78:413–426

Kreiger N, Williams DR, Moss NE (1997) Measuring social class in U.S. public health research: concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health 18:341–378

Lorant V, Deliege D, Eaton W, Robert A, Phillippot P, Ansseau M (2003) Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 157:98–112

O’Hara MW, Stuart S, Gorman LL, Wenzel A (2000) Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57:1039–1045

O’Hara MW, Swain A (1996) Rates and risk of postpartum depression – a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry 8:37–54

Pearlin LI (1989) The sociological study of stress. J Health Soc Behav 30:241–256

Pires SA, Lazear KJ (2004) Maternal depression workshop. Annie E. Casey Foundation Community Health Summit, Washington, DC

Segre LS, Losch ME, O’Hara MW (2006) Race/ethnicity and perinatal depressed mood. J Reproduct Infant Psychol 24:99–106

Segre LS, O’Hara MW (2005) Screening in the U.S. healthcare system. In: Henshaw C, Elliott S (eds) Screening for perinatal depression. Jessica Kinglsey Publishers, London

Surgeon General (1999) Mental health: Culture, race, ethnicity – Supplement. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC

The Postpartum Depression Law (2006) NJSA 42:2–176

Turner RJ, Wheaton B, Lloyd DA (1995) The epidemiology of social stress. Am Sociol Rev 60:104–125

Uehara T, Sato T, Sakado K, Kameda K (1997) Discriminant validity of the Inventory to Diagnose Depression between patients with major depression and pure anxiety disorders. Psychiatry Res 71:57–61

Wells KB, Miranda J, Bauer MS, et al. (2002) Overcoming barriers to reducing the burden of affective disorders. Biol Psychiatry 52:655–675

Wisner KL, Peindl KS, Gigliotti T, Hanusa BH (1999) Obsessions and compulsions in women with postpartum depression. J Clin Psychiatry 60:176–180

Wisner KL, Wheeler SB (1994) Prevention of recurrent postpartum major depression. Hosp Community Psych 45:1191–1196

Zimmerman M, Coryell W, Corenthal C, Wilson S (1986) A self-report scale to diagnose major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 43:1076–1081

Zimmerman M, Coryell W (1987) The inventory to diagnose depression (IDD): a self-report scale to diagnose major depressive disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol 55:55–59

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants MH50524 and a supplement to MH59668 from the National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD. (Drs. O’Hara and Stuart, respectively). The authors would like to thank Laura Gorman, Ph.D. for her assistance with this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Segre, L.S., O’Hara, M.W., Arndt, S. et al. The prevalence of postpartum depression. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol 42, 316–321 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-007-0168-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-007-0168-1