Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Depressive disorders are associated with mortality within 18 months of presentation of diabetic foot ulcers (DFU). The main aim of this study was to determine whether depressive disorder is still associated with increased mortality in people with their first foot ulcer at 5 years.

Methods

This is a 5-year follow-up of a cohort of 253 patients presenting with their first DFU. At baseline, the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) 2.1 was used to define those who met DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 4th edition) criteria for depressive disorder. Cox regression analysis controlled for potential covariates: age, sex, marital status, socioeconomic status, smoking, mean HbA1c, diabetes complications and ulcer severity. The main outcome was mortality at 5 years.

Results

The prevalence of DSM-IV depressive disorder at baseline was 32.2% (n = 82). There were 92 (36.4%) deaths over the 5 years of follow-up. In the Cox regression (n = 246), after adjusting for covariates, baseline DSM-IV depressive disorder was significantly associated with a twofold increased risk of mortality for any depressive episode (HR 2.09, 95% CI 1.34, 3.25), minor (HR 1.93, 95% CI 1.00, 3.74) or major depressive disorders (HR 2.18, 95% CI 1.31, 3.65), compared with patients who were not depressed.

Conclusions/interpretation

Depression is associated with a persistent twofold increased risk of mortality in people with their first DFU at 5 years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetic foot ulcers (DFU) are common in diabetes, with a lifetime risk of developing one estimated at one in four of all patients with diabetes [1]. UK prevalence rates range from 5.1% to 7.4% [2–4], and elsewhere, for instance the Middle East, prevalence rates are 5.9% [5]. Incidence is also high and this varies between 2.1% and 2.2% in the Netherlands [6] and UK [3], to 5.8% in the USA [7]. Risk factors for DFU include peripheral neuropathy, foot deformity, trauma, peripheral vascular disease and oedema [8] and male sex [9]. DFU precede most amputations in people with diabetes and have a significant adverse impact on the individual, healthcare systems and society [10]. People with DFU have to adjust to functional impairment that significantly impedes quality of life [11, 12], and tend to use healthcare resources heavily [13]. Costs associated with DFU are mainly attributed to increased numbers of unscheduled admissions for the treatment of infection and amputation [7, 13].

Depression is twice as common in people with diabetes than in general populations [14, 15] and is associated with adverse outcomes, such as increased morbidity and mortality [16–18]. Depression in diabetes is also associated with non-adherence to diabetes self-care [19], worse glycaemic control [20] and diabetes complications [17]. Previously we reported a high rate (32%) of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edition (DSM-IV) depressive disorder at the time of presentation of first DFU, and that this was associated with a threefold increased risk of mortality 18 months later [21]. We used a research diagnostic interview to assess depression as self-report measures tend to overestimate its prevalence [14]. Similar observations have been reported from secondary analyses of large cohort studies [22–25], but none used a psychiatric clinical interview at baseline, or a population cohort of people with complications and one was limited to older Mexican Americans [25]. One limitation of our original study is that the effect of depression on mortality at 18 months follow-up may have reflected the early stages of adjustment to the sudden onset of disability and change in role and responsibilities, and, if so, that this would be expected to disappear over time, especially if the ulcer heals and the patient gradually adjusts. On the other hand, as depression may have a chronic or relapse remitting course, its effect on mortality rates may be more long-lasting [26, 27]. The aim of this study was to continue the follow-up of this cohort of patients with their first DFU to test if the association between baseline DSM-IV depressive disorder and mortality changes (increases or decreases) over 5-year follow-up.

Methods

A population-based prospective cohort of adults with diabetes with their first ulcer on either foot (baseline ulcer) presenting at all hospital foot and community chiropody clinics between October 2001 and February 2003 was recruited from four health authorities (representing a general population of 2 million residents) in inner city south London, UK. Participants were initially followed up prospectively for 18 months from recruitment. This sample was then followed again, this time up to 5 years from recruitment.

At recruitment, type 1 and type 2 diabetes were defined according to WHO criteria [28]. Ethical approval was sought from local ethics committees of the participating centres and informed consent was obtained for each participant. The case definition for a DFU was: (1) the ulceration was in the anatomical foot; (2) there was a full thickness break in the epithelium with a minimum width of 5 mm; and (3) to exclude severely ischaemic feet, the ankle/brachial ratio was >0.5 and no greater than 1.5 (to exclude those with potential calcification of the medial arteries) at either the dorsalis pedis or posterior tibial sites using Doppler pressure readings. When participants had more than one ulcer at first presentation the largest ulcer was defined as the baseline ulcer [21]. First DFU with duration of greater than 1 year at recruitment were excluded to reduce effects of chronicity on quality of life and adverse outcome. The exclusion criteria were: (1) not fluent in English; (2) independent co-morbid medical condition (such as rheumatoid arthritis); (3) severe mental illness, such as schizophrenia, other psychoses, dementia. Further details of recruitment and tracing have been described previously [21].

At baseline, data on sociodemographic and diabetes-specific status were recorded. We measured age at recruitment, sex, self-report ethnicity, marital status (married/cohabiting, separated/divorced, single) and socioeconomic status according to occupational class [29]. Smoking was coded as non-smoker, ex-smoker or current smoker. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) was used to classify patients who reported hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption (score >8 was defined as having an alcohol problem) [30]. Mean percentage (and millimoles per mole) glycated haemoglobin value was derived from baseline, 12 and 18 months. Macrovascular complications were defined as prior myocardial infarct, coronary angioplasty, coronary artery bypass and peripheral angioplasty or cerebrovascular accident (CVA). Microvascular complications were defined as retinopathy (background or proliferative) measured using digital fundal examination, nephropathy (macroalbuminuria or on dialysis) and neuropathy (vibration perception threshold [VPT] ≥25 V). Ulcer size (square centimetres) was determined using digital imaging [31]; severity of ulcer was graded according to the University of Texas Diabetic Wound Classification System [32]; duration of ulceration (in months) was recorded from first presentation; degree of ischaemia was assessed using the ankle:brachial pressure index (ABPI). Measures at 18 months included as covariates were date of first amputation and of the first recurrent ulceration and the binary variable of whether the baseline ulcer healed.

The main explanatory variable, depression, was measured at baseline using the WHO Schedules in Clinical Assessment and Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) 2.1 [33], which is a diagnostic research clinical interview to determine the presence or absence of minor or major depressive disorder according to the DSM-IV criteria and the methods used have been described in detail [21]. It closely resembles the psychiatric clinical interview and when non-expert SCAN 2.1 raters were compared with expert SCAN 2.1 raters, the sensitivity at diagnosing depression was 59% and the specificity 90% [34]. It is superior to self-report questionnaires for depression, which can only detect a potential case of depression, which should then be confirmed by a clinical interview.

The main outcome was date of death at 5-year follow-up and cause of death of survivors was obtained through the UK’s Central Register Office (www.gro.gov.uk).

Statistical analysis

STATA 11 (Stata, College Station, TX, USA) was used. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to study the relationship between baseline DSM-IV minor and major depressive disorders compared with no depression, with the binary outcome of mortality adjusting for the same baseline potential covariates contained in the analysis of the 18-month follow-up data to ensure comparability. Additional variables (macrovascular complications, neuropathy measured with vibration perception threshold, type of diabetes, presence of alcohol problems [AUDIT score] and treatment with antidepressant therapy at baseline) were investigated to ensure that no other contributing factors had become evident during the longer time frame. The estimated survival curve was plotted such that the adjusted hazard ratios were standardised using the average values of the covariates included in the model, with the exception of severity of ulcer and social class, which were standardised if the ulcer was severe or if the patient was in social class I or II. The analysis was repeated using depression as a binary variable.

Each variable was examined individually to check for the assumption of proportional hazards; this was done by constructing Nelson–Aalen plots. Once the multivariable model had been fitted, the proportionality of the model as a whole was examined by performing the Schoenfeld test [35]. Martingale residuals were plotted against covariates to detect non-linearity. The assumptions of Cox regression were assessed using the Schoenfeld test for the final model and Nelson–Aalen plots for the individual and did not reveal any major violations of the assumptions of proportional hazard.

In order to assess whether the association between depression and mortality differed at different time intervals, the hazard in the first 18 months of follow-up was compared with that in the subsequent 42 months to check for a significant difference. To achieve this, a Lexis expansion was applied to the data and a Poisson regression performed.

In order to see if a patient’s hazard of mortality differed before and after their first amputation, amputation status was considered in the model as a time-updated covariate up to the first 18 months of follow-up.

Results

A total of 262 patients presented with their first DFU, and of these 253 consented and constituted the cohort. Our 5-year follow-up rate was 100% for mortality status. The prevalence of DSM-IV depressive disorder was 32.2% (n = 82) at recruitment. The baseline characteristics of the sample are reported in Table 1. No patients were receiving psychological treatment for depression at baseline. Ten patients were prescribed antidepressants (tricyclic [n = 5] and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor [n = 5]): six of the ten had major depressive disorder and the remaining four had no depression (Table 1). People with depressive disorder were more likely to be younger and have more severe and larger ulcers (Table 1).

During the initial 18 months of follow-up there were 42 (15.8%) deaths, all due to natural causes. In the following 3.5 years there were a further 50 deaths, bringing the total deaths over the 5 years of follow-up to 92 (36.4%). Causes of death included: coronary heart disease (n = 33); CVA (n = 13); infection (n = 31); end stage renal failure (ESRF) (n = 4); cancer (n = 9); complications due to liver disease (n = 1); and diabetic ketoacidosis (n = 1). Twenty-one (12.3%) of 171 non-depressed people and 21 of 82 depressed people (25.6%) died within the first 18 months, and of those remaining alive for the 5-year follow-up, 34 (22.7%) of 150 non-depressed people and 16 of 61 depressed people (26.2%) died within the 1.5–5-year follow-up period. In total, 55 (32.2%) of 171 non-depressed people and 37 of 82 depressed people (45.1%) died within the 5-year period.

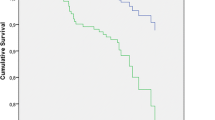

In the Cox regression (n = 246), after adjusting for covariates (age, sex, marital status, socioeconomic status, smoking, mean HbA1c, and ulcer severity), baseline depressive status was significantly associated with mortality (Table 2). The presence of DSM-IV minor and major depressive disorders was associated with an approximate doubling in the likelihood of death (HR 1.93 [95% CI 1.00, 3.74] and HR 2.18 [95% CI 1.31, 3.65] respectively) compared with patients experiencing no depression (Fig. 1). When the analysis was repeated using depression as a binary variable (depressed versus not depressed) a similar pattern was found (HR 2.09, 95% CI 1.34, 3.25) (Fig. 2). The addition of variables, type of diabetes, neuropathy (vibration perception threshold ≥25 V) or the presence of one or more macrovascular complications, into the model did not affect the association between depression and mortality and therefore were not included in the model. Presence of alcohol problems (AUDIT score >8, p = 0.773) and treatment with antidepressant therapy at baseline (overall p = 0.100) were not significantly associated with mortality and not included in the final model, although they did slightly decrease the size of the effect of severe depression (HR 2.02, 95% CI 1.20, 3.39).

Predicted survival curve for participants with and without a DSM-IV depressive disorder. Mean values used were as follows: aged 62 years; mean HbA1c 8.2% (66 mmol/mol); male; single, divorced or widowed; social class I or II; deep ulcer; non-smoker. Solid line, not depressed; dashed line, minor depressive disorder; dotted dashed line, major depressive disorder

There were no significant differences in hazards in the two follow-up time bands, the initial prospective 18 months of follow-up and the subsequent retrospective 42 months of follow-up (p = 0.228). There was no interaction between depression status and time band (p = 0.338) or a time-dependent difference in the effect of depression (p = 0.474).

The assumptions of Cox regression were assessed using the Schoenfeld test for the final model and Nelson–Aalen plots for the individual and did not reveal any major violations of the assumptions of proportional hazard. The Schoenfeld test returned a global p value of 0.359. A plot of the martingale residuals against the linear predictor showed an approximately linear weighted regression line suggesting the link function to be correctly specified. However, the individual p values given by the Schoenfeld test showed evidence of sex violating the proportional hazards assumption, although after stratifying on this variable and re-running the regression the HRs change very little. The Nelson–Aalen plots demonstrated a similar pattern, with the majority of variables showing proportional hazards (satisfied when the hazard functions are roughly parallel). However, the main exception to this was again sex, which showed hazards that appeared to diverge after approximately 2 years.

Discussion

This paper reports on the long-term, 5-year, follow-up of a population-based sample of people with their first DFU who were recruited to a prospective cohort study. We found that the association between depression at recruitment and risk of mortality remained highly significant even 5 years later, representing a twofold increase in risk. These observations were independent of main sociodemographics, HbA1c, ulcer severity and complication status. Although a significant change in risk between the first 18 months of observation and afterwards could not be detected, there was a reduction in magnitude of the association with mortality over time. The smaller differences in relative mortality between depressed and not depressed groups in the second observation period (up to 5 years) compared with the first observation period (up to 18 months) requires further explanation. We do not know whether during the 5 years of observations non-depressed patients at baseline who died after 18 months could have developed depression causing a decrease in risk. However, this study does suggest that any depressive episode regardless of severity has a long-lasting impact. The question as to whether the depression has persisted during the 5 years or whether a history of depression has long-term effects on mortality cannot be addressed in this study. However, there is some evidence that depression in physical long-term conditions tends to be worse and of a more chronic course [26, 27].

The main strengths of this study are that we used a standardised psychiatric interview schedule to generate a diagnosis of clinical depression. Patients were recruited from hospital and community foot clinics, increasing the generalisability of the findings. The main limitation is that the 5-year follow-up data on mortality were collected retrospectively, but as we have achieved 100% data collection on our main outcome this is not a major bias. One limitation of using the SCAN 2.1 to diagnose depression is its low sensitivity (59%) [34] when delivered by non-experts, and therefore we may have underestimated the number of people with depression and therefore the association with mortality. However, prior to starting this intervention inter-rater reliability between the ‘non-expert’ nurse and ‘expert’ SCAN trainer and psychiatrist was 90% [21]. We were also unable to ascertain whether medication use, such as ACE inhibitors, aspirin and statins, differed significantly between the depressed and non-depressed groups. This could be a residual factor. We were not concerned that anxiety was a residual confounder as the prevalence was low and strongly correlated with depression when this was examined in a separate analysis.

Studies of foot clinic populations have repeatedly demonstrated that mortality rates are high [36, 37], and that people who are depressed present with more severe ulceration [38]. Although our study is the only one reporting on the association between incident diabetic foot ulceration, clinical depression and mortality, there is now a growing body of evidence assessing the impact of depression on diabetic foot related outcomes. The Pathways Epidemiologic prospective cohort of 3474 adults with type 2 diabetes study and no prior DFU and amputations found a twofold increased risk of incident DFU in people with self-reported major depression at 4-year follow-up [39]. A prospective cohort of 333 people with diabetic peripheral neuropathy demonstrated that baseline self-reported depression predicted subsequent first (41% of 63 ulcers), but not recurrent, ulceration at 18-month follow-up [40]. More recently, a retrospective study examining the association between diagnosed depression and incident lower limb amputation in people with diabetes found that depression was associated with a 33% increased risk of amputation [18].

Depression is a significant poor prognostic factor for people with diabetes in general, and even more so for people with diabetic foot ulceration. The underlying mechanism of the effect of depression on mortality is still to be explained. Although poor self-care is associated with depression [19, 41], the current body of evidence does not consistently support the theory that reduced foot self-care mediates the association between depression and mortality in diabetic foot disease [21, 40]. For instance, glycaemic control did not mediate the association in this study nor in others [39]. Pathophysiological processes proposed to explain the relationship between depression and cardiac mortality, such as decreased heart rate variability as a result of changes in autonomic tone [42], impaired platelet function [43], cytokine activation [44, 45] and activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis [46, 47], all of which tends to occur in people with diabetic complications, are potential mechanisms, but more evidence is needed to support these theories.

Our study demonstrates that depression is a persistent risk factor for mortality in people with their first DFU. It also raises the question that early treatment of depression may help reduce mortality. The presence of an ulcer should alert clinicians for early screening of depression. Treatment of depression in people with diabetes has consistently demonstrated improvements in depressive symptoms, whether psychological, pharmacological or both [48]. The treatment of depression in people with diabetic foot disease has been less well studied but results from a randomised controlled trial of psychotherapy for inpatients with diabetic foot disease suggest that it may improve depression and foot outcomes [49]. Future research should concentrate on rapid identification and treatment of depression in people with diabetes, and further investigation into whether treating patients who are depressed with foot ulcers improves adverse outcome.

Abbreviations

- ABPI:

-

Ankle:brachial pressure index

- AUDIT:

-

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

- CVA:

-

Cerebrovascular accident

- DFU:

-

Diabetic foot ulcer

- DSM-IV:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edition

- ESRF:

-

End stage renal failure

- SCAN:

-

Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry

- VPT:

-

Vibration perception threshold

References

Singh N, Armstrong DG, Lipsky BA (2005) Preventing foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. JAMA 293:217–228

Kumar S, Ashe HA, Parnell LN et al (1994) The prevalence of foot ulceration and its correlates in type 2 diabetic patients: a population-based study. Diabet Med 11:480–484

Abbott CA, Carrington AL, Ashe H et al (2002) The North-West Diabetes Foot Care Study: incidence of, and risk factors for, new diabetic foot ulceration in a community-based patient cohort. Diabet Med 19:377–384

Walters D, Gatling W, Mulle M, Hill R (1992) The distribution and severity of diabetic foot disease: a community study with comparison to a non-diabetic group. Diabet Med 9:354–358

Al-Mahroos F, Al-Roomi K (2007) Diabetic neuropathy, foot ulceration, peripheral vascular disease and potential risk factors among patients with diabetes in Bahrain: a nationwide primary care diabetes clinic-based patient cohort. Annals of Saudi Medicine 27:25–31

Muller IS, de Grauw WJC, van Gerwen WHEM, Bartelink ML, van den Hoogen HJM, Rutten GEHM (2002) Foot ulceration and lower limb amputation in type 2 diabetic patients in Dutch primary health care. Diabetes Care 25:570–574

Ramsey SD, Newton K, Blough D et al (1999) Incidence, outcomes, and cost of foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care 22:382–387

Reiber GE, Vileikyte L, Boyko EJ et al (1999) Causal pathways for incident lower-extremity ulcers in patients with diabetes from two settings. Diabetes Care 22:157–162

Iversen MM, Midthjell K, Østbye T et al (2008) History of and factors associated with diabetic foot ulcers in Norway: the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study. Scand J Public Health 36:62–68

Reiber GE, Pecoraro RE, Koepsell TD (1992) Risk factors for amputation in patients with diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med 117:97–105

Vileikyte L (2001) Diabetic foot ulcers: a quality of life issue. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 17:246–249

Winkley K, Stahl D, Chalder T, Edmonds ME, Ismail K (2009) A prospective cohort study of quality of life in people with their first diabetic foot ulcer. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 99:406–414

Boulton AJM, Vileikyte L, Ragnarson-Tennvall G, Apelqvist J (2005) The global burden of diabetic foot disease. Lancet 366:1719–1724

Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ (2001) The prevalence of co-morbid depression in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 6:1069–1078

Ali S, Stone M, Peters J, Davies M, Khunti K (2006) The prevalence of co-morbid depression in adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med 23:1165–1173

Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE (2000) Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function and costs. Arch Intern Med 160:3278–3285

DeGroot M, Anderson RM, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ (2001) Association of depression and diabetes complications: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 63:619–630

Williams LH, Miller DR, Fincke G et al (2011) Depression and incident lower limb amputations in veterans with diabetes. J Diabetes Complications 25:175–182

Gonzalez JS, Peyrot M, McCarl LA et al (2008) Depression and diabetes treatment nonadherence: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 31:2398–2403

Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, de Groot M, Carney RM, Clouse RE (2000) Depression and poor glycemic control. A meta-analytic review of the literature. Diabetes Care 23:934–942

Ismail K, Winkley K, Stahl D, Chalder T, Edmonds M (2007) A cohort study of people with diabetes and their first foot ulcer: the role of depression on mortality. Diabetes Care 30:1473–1479

Egede LE, Nietert PJ, Zheng D (2005) Depression and all-cause and coronary mortality among adults with and without diabetes. Diabetes Care 28:1339–1345

Katon WJ, Rutter C, Simon G et al (2005) The association of comorbid depression with mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 28:2668–2672

Zhang X, Norris SL, Gregg EW, Cheng YJ, Beckles GL, Khahn HS (2005) Depressive symptoms and mortality among persons with and without diabetes. Am J Epidemiol 161:652–660

Black SA, Markides KS, Ray LA (2003) Depression predicts increased incidence of adverse health outcomes in older Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 26:2822–2828

Lloyd CE, Nouwen A, Hermanns N, Pouwer F, Underwood L, Winkley K (2010) The epidemiology of diabetes and depression. In: Katon W, Maj M, Sartorius N (eds) Depression and diabetes. Wiley/Blackwell, London, pp 1–28

Lustman PJ, Griffith LS, Freedland KE, Clouse RE (1997) The course of major depression in diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 19:138–143

WHO (1999) Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Report of a WHO Consultation. World Health Organization, Geneva

ONS (2000) Office of National Statistics. ONS standard occupational classification 2000. Volume 1: Structure and description of unit groups. Volume 2: The coding index. Stationery Office, London

Saunders J, Aasland O, Babor TF, de la Fuete JR, Grant M (1993) Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on the early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption. Addiction 88:791–804

Rajbhandari S, Harris N, Sutton M et al (1999) Digital imaging: an accurate and easy method of measuring foot ulcers. Diabet Med 16:339–342

Armstrong DG, Lavery LA, Harkless LB (1998) Validation of a diabetic wound classification system. Diabetes Care 21:855–859

WHO (1997) SCAN: Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry. Version 2.1. World Health Organization, Geneva

Rijinders C, van der Berg J, Hodiamont P et al (2000) Psychometric properties of the schedules for clinical assessment in neuropsychiatry (SCAN-2.1). Social Psychiatry & Epidemiology 35:348–352

Cleves M (2004) Introduction to survival analysis using STATA. Stata Corp., Texas

Jeffcoate WJ, Chipchase SY, Ince P, Game FL (2006) Assessing the outcome of the management of diabetic foot ulcers using ulcer-related and person-related measures. Diabetes Care 29:1784–1787

Winkley K, Stahl D, Chalder T, Edmonds M, Ismail K (2007) Risk factors associated with adverse outcomes in a population-based prospective cohort study of people with their first diabetic foot ulcer. J Diabetes Complications 21:341–349

Monami M, Longo R, Desideri CM, Masotti G, Marchionni N, Mannucci E (2008) The diabetic person beyond a foot ulcer: healing, recurrence, and depressive symptoms. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 98:130–136

Williams LH, Rutter CM, Katon WJ et al (2010) Depression and incident diabetic foot ulcers: a prospective cohort study. Am J Med 123:748–754.e743

Gonzalez J, Vileikyte L, Ulbrecht J et al (2010) Depression predicts first but not recurrent diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetologia 53:2241–2248

Lin EHB, Katon W, von Korff M et al (2004) Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care 27:2154–2160

Carney RM, Freedland KE, Miller GE, Jaffe AS (2002) Depression as a risk factor for cardiac mortality and morbidity: a review of potential mechanisms. J Psychosom Res 53:897–902

Musselman DL, Tomer A, Manatunga AK et al (1996) Exaggerated platelet reactivity in major depression. Am J Psychiatry 153:1313–1317

Owen B, Eccleston D, Ferrier I, Young H (2001) Raised levels of plasma interleukin-1 beta in major and postviral depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 103:226–228

Suarez E, Krishnan R, Lewis J (2003) The relation of severity of depressive symptoms to monocyte-associated proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in apparently healthy men. Psychosom Med 65:362–368

Harris T, Borsanyi S, Messari S et al (2000) Morning cortisol as a risk factor for subsequent major depressive disorder in adult women. Br J Psychiatry 177:505–510

Pariante CM, Lightman SL (2008) The HPA axis in major depression: classical theories and new developments. Trends Neurosci 31:464–468

van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Nuyen J, Stoop C et al (2010) Effect of interventions for major depressive disorder and significant depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 32:380–395

Simson U, Nawarotzky U, Friese G et al (2008) Psychotherapy intervention to reduce depressive symptoms in patients with diabetic foot syndrome. Diabet Med 25:206–212

Acknowledgements

We thank the Wellcome Trust for funding the original study. We thank T. Brugha, University of Leicester, UK, for his guidance on the sensitivity and specificity of the SCAN 2.1.

Contribution statement

KW and HS drafted the manuscript, analysed and interpreted the data. KW, DK, and LHL collected the data. KW, HS, KI, DS, MEE and TC conceived the study design. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and were involved in approving and critiquing the final manuscript for publication.

Duality of interest

The authors declare there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

K. Winkley and H. Sallis are joint first authors of this study.

D. Stahl and K. Ismail are joint senior authors of this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Winkley, K., Sallis, H., Kariyawasam, D. et al. Five-year follow-up of a cohort of people with their first diabetic foot ulcer: the persistent effect of depression on mortality. Diabetologia 55, 303–310 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-011-2359-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-011-2359-2