Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

We assessed country-level and individual-level patterns in patient and provider perceptions of diabetes care.

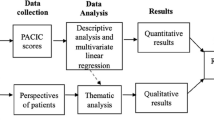

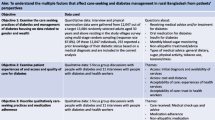

Methods

The study used a cross-sectional design with face-to-face or telephone interviews of diabetic patients and healthcare providers in 13 countries from Asia, Australia, Europe and North America. Participants were randomly selected adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes (n=5,104), and randomly selected diabetes-care providers, including primary-care physicians (n=2,070), diabetes specialist physicians (n=635) and nurses (n=1,122). Multivariate analysis was used to examine the relationships between outcomes and both country and respondent characteristics, and the interaction between these two factors.

Results

Providers rated chronic-care systems and remuneration for chronic care as mediocre. Patients reported that ease of access to care was high, but not without financial barriers. Patients reported moderate levels of collaboration among providers, and providers indicated that several specialist disciplines were not readily available to them. Patients reported high levels of collaboration with providers in their own care. Provider endorsement of primary prevention strategies for type 2 diabetes was high. Patients with fewer socio-economic resources and more diabetes complications had lower access (and/or higher barriers) to care and lower quality of patient–provider collaboration. Countries differed significantly for all outcomes, and the relationships between respondent characteristics and outcomes varied by country.

Conclusions/interpretation

There is much need for improvement in applying the chronic-care model to the treatment and prevention of diabetes in all of the countries studied. Each country must develop its own priorities for improving diabetes care and comparison with other countries can help identify strengths as well as weaknesses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It has been suggested that most healthcare systems are designed to deal with acute health problems rather than chronic health conditions, and therefore provide inadequate treatment for chronic conditions such as diabetes [1, 2]. A review has shown that the use of chronic-care strategies can improve outcomes in chronic disease [3].

Chronic-care models suggest that appropriate care for chronic conditions should be accessible, comprehensive and collaborative, and should focus on prevention [4, 5]. Patients with chronic conditions such as diabetes need to see providers regularly to obtain guidance and assistance in managing their disease. If it is difficult or expensive to obtain care, fewer patients will obtain it and outcomes are likely to be worse [6–10]. Access to healthcare and financial barriers to care can be influenced by patient-level factors (e.g. social resources) as well as system-level factors (e.g. whether care is paid for by patients or provided free), and there may be interactions between factors at the different levels (e.g. patient resources will have less influence on access in a system which provides free care to all).

Chronic care should be comprehensive. Caring for chronic disease requires multiple types of expertise, ranging from a primary-care provider who is familiar with the patient’s full range of needs to a set of specialists who can help manage technically demanding aspects of chronic conditions. If care providers do not possess the necessary expertise, outcomes are likely to be worse. In diabetes care, multi-disciplinary collaborative care by primary-care practitioners collaborating with nurses, dietitians, endocrinologists and other specialists has been shown to improve a variety of diabetes outcomes [11–14].

Chronic care should also be collaborative, both among providers and between patients and providers. Research suggests that effective collaboration among multiple providers is associated with better quality of care [15, 16]. Patient–provider collaboration can also affect diabetes outcomes. Because diabetes care is essentially self-care, patients must be involved in managing their disease, whether through the taking of medication, diet, exercise or other forms of health-related behaviour. Patients are more adherent to self-care recommendations and have better health outcomes when they participate more in treatment decisions [17–19] and are more satisfied with their physician’s communication skills [20–23].

Chronic-care models have very much in common with efforts to prevent as well as treat chronic conditions [5]. Treatment strategies that effectively manage diabetes (glucose-lowering medication and lifestyle modification) can prevent or delay type 2 diabetes [24, 25]. Thus, the endorsement of diabetes-prevention initiatives represents a potential source of support for the chronic-care model.

Although the value of good quality, accessible care has been demonstrated [26], there is little comparative cross-national research on variations in diabetes care, and specifically in the degree to which diabetes care conforms to a chronic-care model. There is substantial cross-national variation in diabetes-care guidelines [27], but it is not clear how these guidelines are reflected in actual care practices. Moreover, multi-national studies often do not distinguish different countries, or they focus exclusively on a single region [28]. While these studies are valuable in their own right, more cross-national, multi-region studies are required.

This paper presents a cross-national assessment of patient and provider perceptions of diabetes care in several continents (Asia, Australia, Europe, North America). In addition to the overall organisation of care for chronic conditions, the paper focuses on several specific aspects of the chronic-care model: access, comprehensiveness, collaboration and prevention. The data set includes measures of: (1) provider perceptions of how well the healthcare system is organised to manage chronic diseases and financial barriers to effective care; (2) patient perceptions of ease of access to providers and financial barriers to access; (3) patient perceptions of collaboration among their providers and how collaborative their relationships with their providers are; and (4) provider endorsement of diabetes-prevention goals.

We examined variations in outcomes across countries and types of respondents and the interactions of these two factors. We hypothesised that financial barriers will vary more across countries than other outcomes (due to differences in payment systems) and that the level of provider collaboration will differ across countries more than patient–provider relationships (because the former reflects more greatly the organisation of different national healthcare systems). We hypothesised that patients’ social resources (occupational attainment, education, marital status) will be more strongly related to financial barriers than to other outcomes and that the impact of social resources on financial barriers will vary by (interact with) country, again due to differences in payment systems.

Subjects and methods

Study background

The larger Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN) study from which these data are taken was designed to identify a broad set of attitudes, wishes and needs among patients and providers in order to lay the groundwork for efforts to improve diabetes care [29, 30]. The DAWN study includes data from patients on demographics, socio-cultural environment, life situation, initial adjustment to diagnosis of diabetes, diabetes history, health status, psychological well-being, and attitudes toward diabetes and its treatment. Providers (physicians and nurses) reported their own practice contexts and behaviours and their treatment-related attitudes, as well as estimates of their patients’ attitudes and perceptions.

Study design

All data are self-reports, gathered during 2001 by interviews conducted face-to-face or by telephone (depending on telephone availability). Interviews took 30–50 min to complete and were based on structured questionnaires. The questionnaires were developed by the multi-disciplinary International DAWN Advisory Panel after review of a variety of diabetes-related questionnaires and focus group interviews with patients, providers and policy makers in eight countries. Wirthlin, an international survey organisation, selected fieldwork firms in each country to field the surveys, including interviewer training and questionnaire translation. In order to avoid bias, potential respondents were not told who the study was sponsored by. Sampling frames varied by country, but all were designed to generate heterogeneous samples from the entire country (except India, where the sample was limited to five regions).

Participants

Interviews were conducted in 11 regions (representing 13 countries): Australia, France, Germany, India, Japan, the Netherlands, Poland, Scandinavia (Sweden, Denmark, Norway), Spain, UK and USA. The Scandinavian samples were evenly divided among the three countries.

The study was conducted with three independent samples of respondents. The first sample (see Table 1) consisted of 2,705 physicians, with a quota of 250 per region, 200 in primary care and 50 specialists (endocrinologists and diabetologists with at least 2 years of experience and treating more than 50 patients per month). For India approximately half the physicians (compared with the quota of 20%) were classified as diabetes specialists, because those who treated more than 50 diabetes patients per month, initiated insulin treatment and accepted diabetes referrals from other physicians were classified as specialists in India. Respondents had to be treating at least five diabetes patients per month and only one physician was selected from a practice.

The second respondent sample consisted of 1,122 nurses, with a quota of 100 per region, 50 specialists, treating more than 50 persons with diabetes a month, and 50 generalists (see Table 1). Treating at least five persons with diabetes per month was an inclusion criterion for the survey and only one nurse was selected from a practice.

Physicians and nurses differed in several characteristics (see Table 1), including years in practice (physicians=15.89±8.95 vs nurses=10.56±7.29).

The third respondent sample consisted of adults with diabetes mellitus, with a quota of 500 per region (see Table 2). Serious illness and depression were exclusion criteria. Sample quotas were established to obtain equal numbers of people with self-reported type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Because the self-reports did not accurately represent type of diabetes, persons were classified as having type 1 diabetes if diagnosed before age 40, and treated with insulin at diagnosis and at the time of the survey; others were classified as having type 2 diabetes. Respondents who did not provide basic demographic data were deleted from analyses, leaving a usable sample of 5,104. Approximately one-third were classified as type 1 diabetes; Japan was an anomaly in that less than 5% were type 1 diabetes.

Ethical approval

This research was conducted according to the Joint Guidelines on Pharmaceutical Research Practice of the British Healthcare Business Intelligence Alliance and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all respondents and participation was voluntary. Ethical approval for use of these data was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Loyola College in Maryland (The Human Subjects Research Committee).

Main outcomes

There were three main provider-reported outcomes, all scored 0–100 with higher scores indicating higher levels of the measure. Of these three, two single-item measures rated the chronic-care system: (1) overall rating of the quality of the chronic-care system (‘Healthcare in this country is well organised for the management of chronic conditions, including diabetes’ [disagree=0/agree=100]); and (2) provider remuneration as a barrier to quality diabetes care (‘The remuneration system for physicians is a barrier to the effective management of diabetes’ [disagree=0/agree=100]). The third provider-reported outcome was: endorsement of diabetes-prevention goals for type 2 diabetes, evaluated as the mean of three questions: (1) ‘There should be a public awareness campaign about diabetes directed toward people at risk’; (2) ‘Any public awareness campaign should concentrate on the prevention of the onset of type 2 diabetes’; and (3) ‘Screening should be available free of charge to all in the high-risk groups’. Scoring: disagree=0/agree=100, alpha for scale reliability=0.64.

There were four main patient-reported outcomes, all scored 0–100. The first, ease of access to providers, was the mean of three questions: (1) ‘How easy is it for you to get to see your doctor when you need to?’; (2) ‘How easy is it for you to get to see your specialist when you need to?’; and (3) ‘How easy is it for you to get to see your nurse when you need to?’. Scoring: very difficult=0/very easy=100; alpha for scale reliability=0.78. The second outcome, financial barriers to care, was based on one question: ‘I find it difficult to pay for my diabetes treatment’ (disagree=0/agree=100). The third patient-reported outcome, quality of provider team collaboration, was also based on one question: ‘Do you think all the people involved in your diabetes treatment talk with each other about your diabetes problems?’ (no=0/yes=100). The fourth and last outcome, quality of patient-provider collaboration, was assessed as the mean of four questions: (1) ‘I have a good relationship with the people I see about my diabetes’; (2) ‘My doctor spends enough time with me’; (3) ‘I feel that I am fully involved in the treatment decisions’ (disagree=0/agree=100); and (4) ‘How easy do you find it to talk to your main doctor?’ (very difficult=0/very easy=100; alpha for scale reliability=0.62).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis used general linear models incorporating effects for country, several respondent characteristics (for providers, all respondent characteristics reported in Table 1 as well as years in practice; for patients, all respondent characteristics reported in Table 2), and the interaction of the respondent characteristics with country. This strategy, which identified country differences after adjusting for differences in the composition of country samples, was determined to be necessary after preliminary analysis showed that the countries differed significantly for all respondent characteristics in each of the three samples.

Country differences were tested by comparing each country’s adjusted mean with the overall adjusted mean. Interactions of country with respondent characteristics determined whether there were differences among countries in how respondent characteristics were related to outcomes. Because each interaction involved so many potential elements (how a relationship in each country differed from each other country), the elements were not subjected to post hoc analysis. Minimum significance level for all analyses was set at p=0.05. Overall (all countries combined) descriptive data were provided for additional measures reported in the text.

Results

The overall provider rating of the quality of the chronic-care system was near the midpoint of the scale (mean=55), with the USA receiving the lowest rating and the Netherlands the highest (38 and 64, respectively) (Fig. 1). Overall, primary-care physicians (mean=57) rated their systems higher than specialists and nurses (49 and 52, respectively). There was a significant interaction between country and discipline; the pattern of differences among providers varied across countries. The relatively poor rating of the chronic-care systems led most physicians (79%) and nurses (81%) to state that diabetes should be a higher priority compared with other conditions.

One general feature of the chronic-care system is the degree to which provider remuneration is a barrier to quality diabetes care (Fig. 2). Overall, primary-care and specialist physicians reported similar levels of barriers, with levels varying significantly across countries (mean=54, range=26–76). Moreover, there was a significant interaction between country and discipline; in some countries primary-care physicians reported that payment was a greater barrier, in other countries specialists reported greater barriers, and there was no difference in other countries.

Patient-reported ease of access to providers was rated high (mean=77, range=65–84), with Scandinavia and the Netherlands rated significantly lower than the overall mean while Australia and France were rated significantly higher (Table 2, Fig. 3). Ease of access to specialist physicians (mean=71) was lower than for primary-care physicians (mean=79) and nurses (mean=80). There was significant variation in perceived access among different patient groups. Women and older patients reported significantly higher ease of access, while those with more diabetes complications reported significantly lower ease of access. Rural residents reported significantly higher ease of access overall, but there was a significant interaction between country and residential location, which indicated that the effect of residence on ease of access varied from country to country.

Patient-reported financial barriers to care varied more across nations than ease of access (mean=26, range=9–64), with several European Union countries having significantly lower barriers and the USA, Poland and India having significantly higher barriers. Financial barriers were significantly higher among those with fewer social resources (lower education/occupation and unmarried), rural residents, those aged 35–49 years, and those with more diabetes complications. The effect of most of these respondent characteristics (all except age) varied significantly across countries.

Patients reported intermediate levels of quality of provider team collaboration, and the differences among countries were greater than for ease of access and patient–provider relationships (mean=51, range=34–67); Japan and Poland were significantly lower than the overall mean while Germany, the Netherlands and Scandinavia were significantly higher (Table 2 and Fig. 3). Patients varied in their perception of the level of provider collaboration. For example, married respondents reported higher levels than unmarried respondents. Overall, reported team care was significantly higher among type 1 patients and lower among type 2 patients not on insulin, but this pattern varied across countries. Although collaborative team care did not vary significantly by residence overall, there was significant variation across countries in the relationship between residence and team care.

One possible reason for the low availability of collaborative team care may be the fact that providers were not at the same site; 40% of patients said this was true for their diabetes-care providers. Among primary-care physicians few reported on-site availability of various diabetes team care disciplines (diabetes specialist physicians=10%, nurse educator=18%, dietitian=16%, behaviouralist=19%, podiatrist=23%, eye specialist=16%), and most (73%) wanted greater availability of providers from one or more of these disciplines. Most physicians (76%) and nurses (80%) identified better communication among providers as another important mechanism for enhancing collaborative care. When asked how communication among providers could be improved, a substantial portion of physicians (36%) and nurses (33%) suggested regular meetings among providers.

Quality of patient–provider collaboration was rated high by patients in all countries (mean=80, range=70–88); Japan, Poland and the Netherlands were significantly lower than the overall mean, while Australia and France were significantly higher (Table 2 and Fig. 3). Ratings were significantly lower for lower status workers, suburban residents, and those with diabetes complications; these patterns did not vary significantly across countries. When asked how the quality of patient–provider relationships could be improved, a substantial portion of physicians (39%) and nurses (30%) suggested longer visits.

Endorsement of diabetes-prevention goals by providers was high among all countries (mean=81, range=75–91) but there were differences among countries: Poland, India and the USA provided higher endorsement, while Scandinavia and the Netherlands were lower (Fig. 4). Primary-care physicians endorsed diabetes-prevention strategies significantly less than nurses and specialist physicians. In addition, there was a statistically significant interaction, with the differences among provider groups varying across countries; in some countries nurses reported highest endorsement, in others specialists reported the highest endorsement, and in a few countries the provider groups were similar.

Discussion

The main findings of this study can be summarised as follows. Physicians and nurses gave modest ratings to the overall quality of the chronic-care system, and there was substantial variation across countries. Physicians identified substantial financial barriers to their provision of quality diabetes care; the level of barrier differed substantially across countries, and according to disciplines within countries. Patients reported high ease of access to providers, but there were substantial financial barriers (variation across countries was highest for this outcome). Patients’ ratings of team collaboration among their providers were relatively low and varied substantially across countries. By the same token, primary-care physicians noted a lack of multi-disciplinary care and a need for more. Patients rated patient–provider relationships as being highly collaborative, with less variation among countries than other outcomes. Finally, there was high support among physicians and nurses for the primary prevention of diabetes, and this support was relatively consistent across countries.

None of the countries received highly positive ratings on all aspects of care examined (Japan’s ratings were most often below the all-country average). However, combining results from different indicators reveals clusters of countries with similar profiles of care/prevention perceptions. Scandinavia, the Netherlands and Germany had relatively high provider ratings of their chronic-care systems, low financial barriers to care, and high collaborative team care. These countries also had low endorsement of primary prevention strategies; this pattern may be reflective of low prevalence of type 2 diabetes (and less need for prevention) with an emphasis on accessible, collaborative care. Poland, India and the USA had relatively low provider ratings of their chronic-care systems, high financial barriers and low collaborative team care. These countries also had high endorsement of primary prevention strategies; this pattern may reflect inadequate existing resources for treatment and prevention. Overall, there seems to be an inverse association at the national level between perceived quality of diabetes care and support for diabetes prevention.

Patient characteristics influenced ratings of care access, comprehensiveness and collaboration. However, these characteristics can have both positive and negative effects. For example, although rural residents reported higher financial barriers to care, they reported easier access and more collaborative patient–provider relationships.

As hypothesised, patients with fewer social resources (unmarried, less education, lower occupation) reported greater financial barriers and less collaborative care. However, the various social resources were not consistently related to all outcomes. Moreover, the effect of resources on financial barriers varied by country, suggesting the role of differing systems of paying for care. Another important patient characteristic was diabetes complications. Patients with complications, who might be defined as medically most in need of quality diabetes care, reported less easy access to care, higher financial barriers, and less collaborative patient–provider relationships. Finally, because the analysis identified independent relationships, the combination of low social resources and high medical need was associated with an even lower level of access and patient–provider collaboration.

The strengths of this study include relatively large samples of diverse patient and provider groups in multiple countries with different cultures and healthcare systems. This allows us to assess systematic variations within and among countries, and to determine what individual traits are related to the outcomes examined.

The major weakness of this study is that it did not examine some important aspects of medical care, i.e. whether the care received meets accepted clinical guidelines and the factors that might influence quality of care received (e.g. local availability of effective treatments and the training of providers). In addition, we have no evidence regarding care outcomes, i.e. how the care received contributed to desired health outcomes and what other factors might influence outcomes.

Nevertheless, several studies have shown that patient perceptions of care are strongly associated with both objective quality of care and actual health outcomes [31–33]. Moreover, subjective perceptions are meaningful in their own right because they can affect patient and provider behaviour, and some have suggested that patient perceptions be included as indicators of quality of care [34–36]. However, it would be useful for future research to compare subjective and objective measures of diabetes care access, comprehensiveness, collaboration and prevention. This would help answer the question of whether the observed country differences are due to actual differences in prevention and care, or to differences in patient and provider beliefs and expectations regarding prevention and care.

Another weakness of this study is the possibility that the samples are not entirely representative. This is especially likely for the patient sample because poorer and more-ill patients may be less likely to be selected for surveys (due to accessibility) and are less likely to respond when contacted [37]. To the degree that this is true, diabetes care is likely to be worse than described here, and this bias is likely to be largest among poorer countries.

Many specific aspects of ideal chronic care were not examined in this study. Coordinated, comprehensive chronic care involves not only collaborative care and appropriate reimbursement, but also self-management support, clinical information systems, decision support, and linkage to community resources [4]. Further research specifying the availability of these additional elements of the chronic-care model would be valuable in assessing the quality of diabetes care among and within the countries studied.

Implications of the study

Patients and providers perceive diabetes care as less than optimal; the ideals of the chronic-care model have not been fully realised in any of the countries studied. But each country has its own profile of assets and liabilities. The data suggest that some countries have better care systems but less support for prevention, or vice versa. Particular patient and provider groups are advantaged in some countries, disadvantaged in others. This suggests that each country must develop its own priorities for improving diabetes care. Comparison with other countries can help identify strengths as well as weaknesses that should be addressed. Nevertheless, it appears that there is much need for improvement in applying the chronic care model to the treatment and prevention of diabetes in all of the countries studied.

Abbreviations

- DAWN:

-

Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs

References

Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T (2002) A primary care home for Americans; putting the house in order. JAMA 288:889–893

Clark CM, Fradkin JE, Hiss RG, Lorenz RA, Vinicor F, Warren-Boulton E (2000) Promoting early diagnosis and treatment of type 2 diabetes. JAMA 284:363–365

Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K (2002) Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, part 2. JAMA 288:1909–1914

Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K (2002) Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA 288:1775–1779

Glasgow RE, Orleans CT, Wagner EH (2001) Does the chronic care model serve also as a template for improving prevention? Milbank Q 79:579–612

Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Osmond D et al (2003) Preventable hospitalizations and access to health care. JAMA 274:305–311

Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Shaw J (2001) Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature 414:782–787

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE et al (2002) Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 346:393–403

McWilliams JM, Zaslavsky AM, Meara E, Ayanian JZ (2003) Impact of Medicare coverage on basic clinical services for previously uninsured adults. JAMA 290:757–764

Karter AJ, Stevens MR, Herman WH et al (2003) Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes Study Group. Out-of-pocket costs and diabetes preventive services: the Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) study. Diabetes Care 26:2294–2299

Sturmburg JP, Overend D (1999) General practice based diabetes clinics: an integration model. Aust Fam Physician 28:240–245

Ovhed I, Johansson E, Odeberg H, Rastam L (2000) A comparison of two different team models for treatment of diabetes mellitus in primary care. Scand J Caring Sci 14:253–258

Litaker D, Mion L, Planavsky L, Kippes C, Mehta N, Frolkis J (2003) Physician–nurse practitioner teams in chronic disease management: the impact on costs, clinical effectiveness, and patients’ perceptions of care. J Interprof Care 17:223–237

Gary TL, Bone LR, Hill MN et al (2003) Randomized controlled trial of the effects of nurse case manager and community health worker on risk factors for diabetes-related complications in urban African Americans. Prev Med 37:230–232

Campbell SM, Hann M, Hacker J et al (2001) Identifying predictors of high quality care in English general practice: observational study. BMJ 323:784–787

Bower P, Campbell S, Bojke C, Sibbald B (2003) Team structure, team climate and the quality of care in primary care: an observational study. Qual Saf Health Care 12:273–279

Rachmani R, Slavachevski I, Berla M, Frommer-Shapira R, Ravid M (2005) Teaching and motivating patients to control their risk factors retards progression of cardiovascular as well as microvascular sequelae of type 2 diabetes mellitus–a randomized prospective 8 years follow-up study. Diabet Med 22:410–414

Williams GC, McGregor H, Zeldman A, Freedman ZR, Deci EL, Elder D (2005) Promoting glycemic control through diabetes self-management: evaluating a patient activation intervention. Patient Educ Couns 56:28–34

van Dam HA, van der Horst F, van den Borne B, Ryckman R, Crebolder H (2003) Provider–patient interaction in diabetes care: effects on patient self-care and outcomes. A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 51:17–28

Piette JD, Schillinger D, Potter MB, Heisler M (2003) Dimensions of patient–provider communication and diabetes self-care in an ethnically diverse population. J Gen Int Med 18:624–633

Harris LE, Luft FC, Rudy DW, Tierney WM (1995) Correlates of health care satisfaction in inner-city patients with hypertension and chronic renal insufficiency. Soc Sci Med 41:1639–1645

Alazri MH, Neal RD (2003) The association between satisfaction with services provided in primary care and outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 20:486–490

Kerr EA, Smith DM, Kaplan SH, Hayward RA (2003) The association between three different measures of health status and satisfaction among patients with diabetes. Med Care Res Rev 60:158–177

Lindstrom J, Eriksson J, Valle TT et al (2003) Prevention of diabetes mellitus in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance in the Finnish diabetes prevention study: results from a randomized clinical trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 14 [Suppl 2]:108–113

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE et al (2002) Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 346:393–403

Kuzel AJ, Woolf SH, Gilchrist VJ et al (2004) Patient reports of preventable problems and harms in primary care. Ann Fam Med 2:333–340

Burgers JS, Bailey JV, Klazinga NS, Van Der Bij AK, Grol R, Feder G (2002) Inside guidelines: comparative analysis of recommendations and evidence in diabetes guidelines from 13 countries. Diabetes Care 25:1933–1939

Gagliardino JJ, de la Hera M, Siri F (2001) Evaluacion de la calidad de la asistencia al paciente diabetico en America Latina. [Evaluation of the quality of care for diabetic patients in Latin America]. Rev Panam Salud Publica [Pan Am J Public Health] 10:309–317

Alberti G (2002) The DAWN (Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs) study. Pract Diabetes Int 19:22–24

Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Lauritzen T, Snoek FJ, Matthews DR, Skovlund SE (2005) Psychosocial problems and barriers to improved diabetes management: results of the cross-national Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN) study. Diabet Med 22:1379–1385

Narayan KM, Gregg EW, Fagot-Campagna A et al (2003) Relationship between quality of diabetes care and patient satisfaction. J Natl Med Assoc 95:64–70

Gross R, Tabenkin H, Porath A et al (2003) The relationship between primary care physicians’ adherence to guidelines for the treatment of diabetes and patient satisfaction: findings from a pilot study. Fam Pract 20:563–569

Alazri MH, Neal RD (2003) The association between satisfaction with services provided in primary care and outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 20:486–490

Chin M, Muramatsu N (2003) What is the quality of medical care? Rashomon-like relativism and real-world applications. Perspect Biol Med 46:5–20

Peyrot M, Cooper P, Schnapf D (1993) Consumer satisfaction and perceived quality of outpatient health services. J Health Care Mark 13:24–33

Groves T, Wagner E (2005) High quality health care for people with chronic diseases: what patients with chronic conditions really need. BMJ 330:609–610

Zaslavsky AM, Zaborski LB, Cleary PD (2002) Factors affecting response rates to the consumer assessment of health plans study survey. Med Care 40:485–499

Acknowledgements

The DAWN study was initiated and funded by Novo Nordisk, whom we thank for providing access to the data presented in this paper. The preparation of this paper was supported by a grant to the first author from Novo Nordisk Pharmaceuticals. Aggregate country-specific data may be made available for local quality-of-care improvement activities (see http://www.dawnstudy.com). M. Peyrot performed the statistical analysis. M. Peyrot and R. R. Rubin drafted the paper. T. Lauritzen, S. E. Skovlund, F. J. Snoek, D. R. Matthews and R. Landgraf contributed to study design, reviewed drafts of the paper and suggested revisions. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results and approved the final draft. The International DAWN Advisory Panel members are: Ib Brorly, Denmark; Ruth Colagiuri, Australia; P. Geelhoed-Duijvestijn, the Netherlands; Hitoshi Ishii, Japan; Line Kleinebreil, France; Rüdiger Landgraf, Germany; Torsten Lauritzen, Denmark; David Matthews, UK; A. Ramachandran, India; Richard Rubin, USA; Frank Snoek, the Netherlands; Giacomo Vespasiani, Italy.

Duality of Interest All authors except M. Peyrot are on the International DAWN Advisory Panel. M. Peyrot, R. R. Rubin, T. Lauritzen and R. Landgraf have received grants, and fees for consulting and lecturing from Novo Nordisk, the sponsor of this study. S. E. Skovlund is an employee of Novo Nordisk.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

International DAWN Advisory Panel., Peyrot, M., Rubin, R.R. et al. Patient and provider perceptions of care for diabetes: results of the cross-national DAWN Study. Diabetologia 49, 279–288 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-005-0048-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-005-0048-8