Abstract

Problematic social media use (PSMU) among adolescents has raised global concern in the current digital age. Despite the important role of perceived social support in adolescents’ PSMU has been examined, possible different influences between perceived support from family and friends are still unknown. To address the gap, the present study aimed to examine how perceived support from family and friends is associated differently with PSMU and the mediating roles of resilience and loneliness therein. A sample of 1056 adolescents was recruited to complete standard questionnaires. Mediation analysis showed that resilience and loneliness mediated this association partially between perceived support from family and PSMU but totally between perceived support from friends and PSMU. Further, ANOVA-based analysis showed that influences of perceived support from family and friends on PSMU were mutually independent, and there was no interaction between them. Our results not only highlight different and independent impacts of perceived support from family and friends on PSMU, but also clarify the mediating mechanisms linking perceived social support to adolescent PSMU.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the current information age, social media has been more and more popular, especially during the ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic. Due to worldwide lockdown measures, social media correspondingly becomes even more integral to social lives when face-to-face contact is limited (Drouin et al., 2020; Geurts et al., 2022). As an important part of adolescent leisure activities, social media can provide a convenient venue for them to seek social support and express loneliness to others (Cauberghe et al., 2021; O’Keeffe et al., 2011; Stockdale & Coyne, 2020), thus inevitably increasing their social media use (Liu & Ma, 2020; Marengo et al., 2022). It is also noteworthy that social media use is mainly formed in early adolescence (Abi-Jaoude et al., 2020; CNNIC, 2020). Although social media brings many conveniences to adolescents such as socializing, passing time, and educational motives (Horzum, 2016), its negative effects such as social media dependence and problematic social media use have become more and more serious. Problematic social media use (PSMU) is defined as unplanned and impulsive use of social media (Brand et al., 2016; Turel & Qahri-Saremi, 2016), which could cause a host of negative consequences including school burnout (Walburg et al., 2016), social media fatigue (Xiao & Mou, 2019), social isolation (Meshi & Ellithorpe, 2021), sleep disturbances (Tandon et al., 2020), and poor mental health (Lin et al., 2021; Reissmann et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018), etc. For example, adolescents with PSMU show lower interest in offline leisure activities with others (Andreassen, 2015), which could do harm to interpersonal relationships and metal health.

To investigate what and how potential antecedents influence the occurrence of PSMU among adolescents, we adopted the theory of the Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) to build the theoretical framework (Brand et al., 2016). Following the I-PACE model, PSMU is comprehensive consequence of core characteristics, negative coping styles, maladaptive emotion regulation, and impaired executive functions. The I-PACE model posits that social support not only represents one of the most core characteristics in the process of adolescent PSMU, but also could be related to adolescent PSMU through the capacity for coping strategies or mood dysregulation indirectly (Brand et al., 2016, 2019; Wegmann et al., 2021). Many recent studies have implicated perceived social support was found to be a protective factor in individual development and negatively associated with PSMU in adolescence (Casale et al., 2014; Kırcaburun et al., 2019; Shensa et al., 2017, 2020). For instance, adolescents who possess lower levels of perceived social support are more likely to spend more time on social media and report higher PSMU (Meshi & Ellithorpe, 2021; Shensa et al., 2020). Although previous research investigated perceived social support and relevant individual factors, such as resilience and loneliness, could affect the individual PSMU (Hou et al., 2017; Huang, 2022), they usually treated perceived social support as a whole (Alimoradi et al., 2019) and obtained inconsistent findings. Thus, using the I-PACE model as the theoretical framework, the current study aims to examine a conceptual model in which (a) the possible different associations between perceived social support from family and friends on PSMU and (b) the indirect associations between perceived social support and PSMU via the mediating roles of resilience and loneliness.

Perceived Social Support and PSMU

Perceived social support is multidimensional and defined as individual beliefs about how much the support received from family, friends, and significant others (Winemiller et al., 1993; Zimet et al., 1988), which has a great influence on individual mental health and well-being (Lin et al., 2021). For adolescents, support from family and friends are two influential sources of perceived social support during their development. According to the I-PACE model, social support as the predisposing factor can directly contribute toward PSMU. It is notable that previous studies provided some insights into the possible different influences of perceived support from family and friends on the PSMU in spite of without direct examination. To be specific, perceived support from family, as the most indispensable and influential source for adolescents’ development, might be a significant protective factor for PSMU (Badenes-Ribera et al., 2019). When family members provide adolescents with a supportive environment that optimizes their development, adolescents may make proper use of social media. Relevant meta-analysis studies found that problematic behaviors in adolescents could be influenced by their family support (Bo et al., 2018; Peris et al., 2021; Vannucci et al., 2020). According to the uses and gratifications theory (Ryan et al., 2014; Sundar & Limperos, 2013), individuals may actively use different social media platforms to fulfill personal and social needs when real-life interactions do not match their expectations. In line with this, adolescents raised by lower quality parent–child interactions would perceive insufficient support from family, urging them to seek refuge from friends in social media (Badenes-Ribera et al., 2019; McDougall et al., 2016; Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., 2020). It is worth noting that friends become gradually important with the start of adolescence, and social media usually serves as a complementary platform for relational rewards (Rousseau et al., 2019). The conceptual framework of media multiplexity theory (Haythornthwaite, 2002, 2005; Ledbetter et al., 2011) is used for understanding friends’ influences on adolescent PSMU. A positive relationship between friendship quality and social media intensity, as well as the number of social media, has been revealed among adolescents (Antheunis et al., 2016; Katja et al., 2016; Valkenburg & Peter, 2007). Specifically, in a large sample of 3068 early adolescents, Antheunis et al. (2016) found that adolescents were encouraged to use social media to bond friendships via online interaction; thus, friendship quality was a powerful predictor of time spent on social networking sites. Based on theoretical and empirical evidence, it is reasonable to consider that perceived support from family acts as an important protective factor, while perceived support from friends seems to be a risk factor for the onset of PSMU.

The Mediating Role of Resilience

As a positive personal feature, resilience is defined as an extraordinary human capacity that enables individuals to overcome adversity (Rutter, 2013). People with high levels of resilience are typically characterized by optimism, engaging the support of others, realistic sense of control, and tolerance of negative affect, which can drive them successfully to withstand psychological disturbance (Connor & Davidson, 2003; Lutha & Cicchetti, 2000). For instance, adolescents with higher levels of resilience were especially less likely to engage into problem behaviors, such as tobacco and substance misuse (Goldstein et al., 2013; Weiland et al., 2012), as well as problematic or excessive Internet-related activities (Canale et al., 2019; Navarro et al., 2018; Sage et al., 2021). Regarding social media use, Hou et al. (2017) found that resilience was negatively associated with problematic social networking site usage among adolescents. Together, previous findings suggested that higher levels of resilience could reduce adolescents’ PSMU. Additionally, resilience is developed and influenced by outer factors. Adolescents with low social support have lower resilience than those who have higher supportive relationships (Mcdonald et al., 2019). A supportive environment can foster a positive adaptation of social media use; thus, it is less likely to develop problematic or uncontrolled behaviors. Numerous studies also confirmed that resilience may play a mediating role to mitigate emotional and problematic behaviors in adolescents (Arslan, 2016; Jin et al., 2021; Reuben et al., 2012). Thus, perceived social support might affect PSMU through resilience.

The Mediating Role of Loneliness

At the same time, as an undesirable feeling when they fail to achieve desired social relationships or interaction (Perlman & Peplau, 1981), loneliness is not only a prominent feeling among adolescents, but is also closely associated with their adaptation. Researchers have consistently found that lonely individuals may tend to engage in social media to satisfy the desire to reconnect (Oliveira et al., 2016; Smock et al., 2011; Song et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2018). For instance, Wang et al. (2018) investigating a large sample of 1188 high school students found that compared with adolescents with low levels of loneliness, those students who experienced moderate and high levels of loneliness tended to misuse social media. Furthermore, a meta-analysis investigating PSMU in all platforms revealed that greater loneliness can predict longer time spent on social media (Huang, 2022). With respect to the I-PACE model, the results of several studies emphasized loneliness as a mediating variable between perceived social support and PSMU. Specifically, perceived social support provides emotional comfort and adaptive coping strategies for adolescents to cope with difficulties (Ouyang et al., 2020). Adolescents who perceive more positive social support may experience fewer negative emotions, such as loneliness (Kapıkıran, 2013; Kong & You, 2013). Therefore, a lack of perceived real-life social support may cause more time spent on social media to protect against negative mental health outcomes (e.g., loneliness). This is also in line with the uses and gratifications theory, which indicates that individuals use media to fulfill their needs (Ryan et al., 2014; Sundar & Limperos, 2013). Consequently, less perceived social support could predict loneliness (Ronen et al., 2016), and then social media may be a valuable means to fulfill interpersonal relationship wants and provide necessary social support (Song et al., 2014; Süral et al., 2019), which in turn significantly increases social media use.

The Multiple Mediation Model

In addition, resilience and loneliness are two possible contributing and mediating factors to be associated between perceived social support and the PSMU among adolescents. The I-PACE model states that PSMU is the result of comprehensive consequences (Brand et al., 2016). Therefore, perceived social support, resilience, and loneliness may jointly affect PSMU. Moreover, the interactions between external factors and internal factors facilitate emotion adjustment (Brand et al., 2016). Additionally, resilience theory claims that resilient individuals are more effective to regulate their maladaptive emotions (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005). Adolescents with higher resilient character have more capacities for coping strategies to overcome loneliness (He & Xiang, 2022; Rew et al., 2001), and this preventive mechanism helps them to refrain from falling into the PSMU. Thus, loneliness may be influenced both by external factors, such as perceived social support, as well as internal factors, such as resilience. Hence, the multiple mediation models may provide more accurate mechanisms for understanding how different sources of perceived social support are related to PSMU with the mediating roles of resilience and loneliness, as well as for inspiring adolescents to use social media in a proper way.

The Present Study

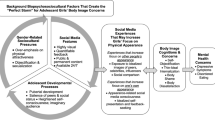

Based on the I-PACE model and previous empirical research, the present study investigated the possible different functions between perceived support from family and perceived support from friends in the PSMU. Moreover, we also aimed to examine the interrelationships between perceived social support, resilience, loneliness, and the PSMU. Hence, we hypothesized that (Fig. 1):

-

H1: Perceived support from family and friends might have different relationships with PSMU.

-

H2: Resilience might mediate the relationship between perceived social support and PSMU. Specifically, both perceived support from family and friends might be positively correlated with resilience, which in turn would negatively predict PSMU.

-

H3: Loneliness might mediate the relationship between perceived social support and PSMU. Specifically, both perceived support from family and friends might be negatively correlated with loneliness, which in turn can positively predict PSMU.

-

H4: Resilience and loneliness would mediate the association between perceived social support and PSMU in both parallel and sequential ways. Specifically, perceived support from family would negatively predict PSMU through (a) the mediating effects of resilience or loneliness in a parallel way and (b) the sequential mediating effect of resilience and loneliness. On the other side, perceived support from friends would positively predict PSMU through the same pathway.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

A total of 1056 students from two middle schools were recruited to complete standard questionnaires and demographics in central China. Before the survey was conducted, children gave their verbal informed consent, and their primary caregiver provided written informed consent for them. All participants were guaranteed that their answers would be kept confidential and used solely for academic research. During data collection, well-trained data collectors gave standardized instructions in front of the class. If students had any questions during the study, they could raise their hands to ask research assistants. After excluding the extreme behavioral performance, 953 participants (age range = 12–17; mean age = 14.16, SD = 1.21; 497 girls) were included for follow-up data analysis.

Instruments

Perceived Social Support

Adolescents’ functional support was assessed using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (Zimet et al., 1988). The MSPSS scale is a 12-item scale assessing three domains of support: family, friends, and significant others. All items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree). For the purpose of the current study, we adopted two subscales of the MSPSS to evaluate the individual’s status of perceived support from family and friends. Four items (e.g., my family is willing to help me make decisions) were used to assess the level of perceived support from family (total scores, 4–28), and another four items (e.g., I can count on my friends when things go wrong) were used to assess the level of perceived support from friends (total scores, 4–28). Scores were averaged across all items, with higher scores indicating better quality of perceived support from family or friends. The MSPSS showed good internal consistency for the overall scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.94), 0.91 for its family subscale and 0.91 for its friend subscale in the present study.

Resilience

Adolescents’ resilience was assessed using the Connor–Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) (Connor & Davidson, 2003; Yu & Zhang, 2007). The scale was revised slightly to accommodate the Chinese culture, and it involved 25 items (e.g., I am able to adapt to change). All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from1 (never) to 5 (very often). The Chinese version of CD-RISC has been widely used in Chinese adolescents and proved to be good in validity and reliability (Gong et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2011). The range of total scores on the scale was 35–125. Scores were averaged across all items, with higher scores indicating higher levels of resilience. The scale showed good internal consistency in the present study (Cronbach’s α = 0.93).

Loneliness

Adolescents’ loneliness was assessed using the UCLA Loneliness Scale (version 3) (Russell, 1996). The UCLA Loneliness Scale had good reported validity and reliability in various groups and cultures (Arimoto & Tadaka, 2019; Lasgaard, 2007), including Chinese sample (He et al., 2022; Tu & Zhang, 2015). The scale contained 20 items (e.g., “I often feel a lack of companions”), in which participants rated it on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). The range of total scores on the scale was 20–77. Scores were averaged across all items, with higher scores indicating a greater frequency of feeling loneliness. The scale showed good internal consistency in the present study (Cronbach’s α = 0.92).

Problematic Social Media Usage

The Adolescent Problematic Mobile Social Media Usage Assessment Questionnaire was used to assess the PSMU in adolescents (Jiang, 2018). It consisted of 20 items and encompassed five dimensions, including viscosity increase, physiological damage, omission anxiety, cognitive failure, and guilt. A sample item was “I can’t remember how many times I unconsciously browse mobile social media and check the status every day.” For each item, participants were instructed to answer on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (was not suitable to me at all) to 5 (was suitable to me very well). The range of total scores on the scale was 20–100. Scores were averaged across all items, with higher scores indicating higher levels of problematic social media use. The scale showed good internal consistency in the present study (Cronbach’s α = 0.92).

Data Analysis

All data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 25 and conducted in the following three steps (Fig. 2). First, we calculated the descriptive statistics and correlations between main variables. Second, we used model 6 of PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013) to test this multiple mediation model, respectively. In specific, perceived support from family (or perceived support from friends) was the predictor, resilience was the first mediator, loneliness was the second mediator, and PSMU was the dependent variable. Additionally, we controlled gender and age as covariates when testing the hypotheses of the present study given that these factors have demonstrated associations with PSMU among adolescents (Andreassen et al., 2017; Heffer et al., 2019; Sampasa-Kanyinga & Lewis, 2015; Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., 2020). The multiple mediation model was based on regression analysis using a bootstrap method (sampling repeated 1000 times) to construct 95% confidence intervals for significance testing in the hypothesized indirect pathways. Finally, we adopted the analysis of variance analyses (ANOVA) to further explore whether the interaction between perceived support from family and friends on the PSMU existed. To be specific, we divided the participants equally into the high group (average scores, > 5; n = 526) and low group (average scores, < 5; n = 427) by perceived support from family and more group (average scores, > 5.5; n = 439) and less group (average scores, < 5.5; n = 514) by perceived support from friends.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Correlations, means, and standard deviations of the main variables were presented in Table 1. Specifically, both perceived support from family and perceived support from friends were positively correlated with resilience and negatively correlated with loneliness. Resilience was negatively correlated with loneliness and PSMU, and positive correlation was found between loneliness and PSMU. More importantly, perceived support from family, as well as perceived support from friends, was negatively correlated with PSMU. These results provided preliminary evidence for the multiple mediation analyses.

Multiple Mediation Analyses

In order to explore whether perceived social support may play different roles in PSMU and whether the unique and sequential mediating effects of resilience and loneliness existed in this relationship, we used model 6 of PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013) to test the multiple mediation model. As Fig. 3 shown, the direct relation was significant for perceived support from family, but not for perceived support from friends (perceived support from family, β = –0.08, p < 0.05; perceived support from friends, β = 0.08, p = 0.052), indicating that the sources of perceived social support play different roles to influence PSMU. Furthermore, perceived support from family positively predicted resilience (β = 0.22, p < 0.001) and negatively predicted loneliness (β= –0.11, p < 0.01). Similarly, perceived support from friends positively predicted resilience (β = 0.27, p < 0.001) and negatively predicted loneliness (β = –0.40, p < 0.001). Resilience negatively predicted loneliness (β = –0.30, p < 0.001) and PSMU (β = –0.22, p < 0.001). Loneliness positively predicted PSMU (β = 0.18, p < 0.001). Furthermore, the direct, indirect, total effects, and the 95% confidence intervals were displayed in Table 2. Results revealed that all indirect effects were significant. Taken together, results indicated that resilience and loneliness mediated this association partially between perceived support from family and PSMU but totally between perceived support from friends and PSMU.

Analysis of Variance Analyses

To further explore whether the interaction between perceived support from family and friends on the PSMU existed, we conducted a 2 × 2 ANOVA with factors for the level of perceived support from family (high vs. low) and degree of perceived support from friends (more vs. less). We first performed Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances (p = 0.96), which indicated homogeneity. Consistent with the mediation findings (Table 3), the ANOVA results showed that there was a significant main effect on the level of perceived support from family, with high-level individuals of perceived support from family possessing less PSMU than low-level individuals [F (1, 947) = 27.39, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.03]. However, there was no difference between the more degree and less degree in perceived support from friends [F (1, 947) = 0.08, p = 0.80, ηp2 < 0.01]. More importantly, there was no interaction between the level of perceived support from family and the degree of perceived support from friends [F (1, 947) = 0.12, p = 0.72, ηp2 < 0.01], which suggested that the influences of perceived support from family and friends on PSMU were mutually independent. Thus, our results indicated that compared with friends, perceived support from family was the first and vital factor for adolescent PSMU.

Discussion

In the present study, we constructed a multiple mediator model to shed light on how perceived social support from family and friends is associated differently with PSMU and possible mediating roles of personality factors and emotional factors utilizing the I-PACE model. The results showed that perceived support from family and friends were related to the PSMU through different pathways among adolescents after controlling for gender and age. That is, perceived support from family was significantly negatively associated with PSMU directly, while perceived support from friends could not predict PSMU. In addition, both perceived support from family and friends could predict the PSMU indirectly through the mediating roles of resilience and loneliness. Finally, compared with perceived support from friends, we found perceived support from family was the major and vital factor for PSMU.

Relationship Between Perceived Social Support and PSMU

Our results provided the first evidence for highlighting the sources of perceived social support that play different and independent roles in adolescent PSMU, which supported H1. On one hand, the direct relation was negatively significant for perceived support from family, which suggested that adolescents who perceived more positive support from family may be less likely to develop the PSMU, which is consistent with the I-PACE model. As important members of the family, supportive family relationships could provide adolescents with emotional care to optimize adolescents’ resilience and overcome feelings of loneliness. Therefore, adolescents who perceive a supportive climate at home are more likely to properly use social media and seek help from families when encountering difficulties online. This is also congruent with prior research which underlines the primacy of families throughout childhood and adolescence (e.g., Rueger et al., 2016). Consequently, perceived support from family might have an impressive and direct positive effect on eliminating PSMU.

On the other hand, the direct effect of perceived support from friends on the PSMU was the opposite. Perceived support from friends could not predict the PSMU in the present multiple mediation model. Our study demonstrated that adolescents who perceive supportive friendships in the offline world will increase their motivation to use online communication technologies, which lends support to the uses and gratifications theory and media multiplexity theory (Ledbetter et al., 2016). That is, adolescents who have already received enough care and support from friends in real-life interactions may allow social media as another venue to nourish existing friendships (Valkenburg & Peter, 2007). Higher levels of perceived support from friends may enhance adolescents’ frequency of social media use in order to maintain friendship-connected support. Thus, the desire for seeking support from friends urges adolescents to use social media, which may even result in PSMU.

Importantly, further ANOVA revealed the independence between perceived support from family and friends on PSMU. To be specific, individuals who possessed higher levels of perceived support from family contributed to lower PSMU, which was not affected by the degree of perceived support from friends. Thus, family support is not only one important aspect of perceived social support, but also the most influential factor of familial atmosphere and functioning. Likewise, individuals who reported low levels of perceived support from family could increase the risk of PSMU, no matter how much friends support they perceived. Taken together, these findings are consistent with previous findings that friends gradually gain importance from childhood to adolescence; however, family is still an ongoing influence on adolescent growth process (Gunuc & Dogan, 2013).

The Mediating Role of Resilience

As expected, resilience mediated the association between perceived social support and PSMU, which was in line with the theoretically formulated hypothesis (H2). This suggested that adolescents receiving either low levels of perceived support from family or friends would decrease the capacities of resilience, and, in turn, these adverse experiences may make them take negative coping styles by impulsive using social media. These results are consistent with previous theoretical assumptions that resilience is an important mechanism that explains why support sources are related to problematic behaviors (EL Rawas et al., 2020). Additionally, it is validated that resilience as a protective role in preventing the development of problematic behaviors (Hughes et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2022). This result also expands the I-PACE model of Brand et al. (2016). Resilient adolescents might possess specific characteristics, such as a high tolerance for negative feelings, which is less likely to develop a maladaptive cognitive bias and then prevent individuals from forming PSMU.

The Mediating Role of Loneliness

We also found that perceived social support could relate to adolescent PSMU through loneliness, which was in line with the theoretically formulated hypothesis (H3). Specifically, both perceived support from family and perceived support from friends were negatively significantly associated with loneliness. Consistent with the uses and gratifications theory (Sundar & Limperos, 2013), the results reconfirmed the view that social needs were associated with adolescents’ loneliness. To be specific, loneliness usually happened when one lacked an intimate relationship with others or was unable to participate in supportive social networks. It is worth noting that adolescents are the particularly high-risk group who report their loneliness at least sometimes (Qualter et al., 2015). When suffering from loneliness, adolescents may have serious consequences for poor physical and mental health. Adolescents with adequate perceived support from family and friends may better cope with unpleasant experience of loneliness. Therefore, adolescents who have positive family and friends interactions cause fewer emotional difficulties such as loneliness, which eventually reduce PSMU (Cauberghe et al., 2021). Moreover, the strength of perceived support from friends with loneliness was stronger than that of perceived support from family; that is, perceived support from friends showed a larger effect in predicting loneliness. This finding was congruent with a previous study which demonstrated that although friendship and parental support were both important intimate relationships for adolescents, friendship quality was the better predictor of loneliness (Corsano et al., 2017).

The Multiple Mediation Model

Importantly, resilience and loneliness mediated the relationship between perceived social support and PSMU in a unique and sequential way, which was in line with the theoretically formulated hypothesis (H4). Indeed, the present findings revealed that adolescents’ perception of support from family and friends was related to their psychosocial adaptation and emotions. The multiple mediation findings confirmed that resilience and loneliness partially mediated the association between perceived support from family and PSMU, whereas mediators fully mediated the association between perceived support from friends and PSMU, which suggested that mediators played different and vital roles in the relationship between perceived social support and PSMU. Moreover, the relationship between perceived social support and PSMU was also sequentially mediated by resilience and loneliness. We also found that resilience could negatively predict loneliness, which was consistent with previous studies (He & Xiang, 2022). Taken together, the influences of perceived support from family and friends on PSMU during adolescents may be quite different and independent. Clarifying the relationship of resilience and loneliness between different perceived social supports and PSMU in the multiple mediation model contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the different pathways linking perceived social support to PSMU.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations should be clarified. Firstly, the present findings are based on the cross-sectional data, which could not conclude any causal relations between perceived social support and PSMU. Future studies are invited to adopt longitudinal designs to clarify the causal relationships among the observed associations in adolescence. Secondly, we collected all the data through hypothetical scenarios based on participants’ self-reports, which might have been subject to well-known biases. Future studies are recommended to holistically collect data from multiple sources to avoid possible biases in responding. Thirdly, since adolescents from different cultures depending on their parents and friends are not all the same, the findings only from just two local middle schools may limit the generalizability of our findings. Future studies are recommended to investigate diverse groups and compare cultural differences to verify our findings. Finally, although our study focused on the external environment (i.e., perceived support from family, perceived support from friends) and individual factors (i.e., resilience and loneliness) and provided valuable insights into adolescents’ PSMU, it ignored some significant others, such as teachers, might also play a potential role in the relationship between perceived social support and PSMU. Future studies should take significant others into more comprehensive consideration and provide a more integrated mechanism.

Implications

Despite its limitations, our study, for the first time, highlighted the positive and vital status of perceived social support from family in PSMU and clarified different and independent roles between perceived social support from family and friends in PSMU for adolescents. From a theoretical perspective, current findings support the I-PACE model (Brand et al., 2016, 2019) and uses and gratifications theory (Sundar & Limperos, 2013), demonstrating that social support as the predisposing factor can predict social media use. Social support is a basic need for adolescents to continue their social relationships at the desired level (Gunuc & Dogan, 2013), to withstand psychological disturbance and to overcome feelings of loneliness. More importantly, we integrated previous research, and theoretical findings to fill existing gaps in how different sources of perceived social support (i.e., perceived support from family and perceived support from friends) were associated with adolescents’ PSMU. Moreover, our findings move beyond demonstrating direct effects by identifying the mediating roles of resilience and loneliness in this association. The findings contribute to the understanding of the underlying mechanism of the PSMU and expand prior theories such as I-PACE model. It is worth noting that both PSMU and social media addictions are the result of social media overuse. Unlike addiction criteria such as salience, tolerance, mood modification, and withdrawal (Griffiths, 2005), PSMU tends to be momentary, impulsive, and irrational which is largely regarded as a bad habit (Turel & Qahri-Saremi, 2016). PSMU might turn into social media addiction under certain circumstances (Andreassen et al., 2017). Currently, there is a lack of specific criteria when drawing the line between social media addiction and PSMU. In our study, adolescents may be less addictive potential to develop an uncontrollable urge to use social media according to the mean scale score for PSMU.

Moreover, the present study also has significant practical implications. First, family support should be emphasized as the most effective effort to prevent adolescents from PSMU. Thus, building supportive interpersonal relationships among family members and teaching them how to appropriately use social media use is critical to adolescents. Second, adolescence is a high-risk developmental period accompanied by high risk and high plasticity in personalities and emotions. Therefore, it is necessary for parents and peers to make efforts to provide close and supportive relationships for adolescents to help them build higher resilience and alleviate loneliness. For example, a school curriculum aimed at internal strengths and external resources could provide the foundation for positive adaption in adolescence, which may also enhance resilience (El Rawas et al., 2020).

Conclusion

In summary, the present study is an important step toward a better understanding of how perceived support from family and friends is associated differently with the PSMU and the mediating roles of resilience and loneliness therein. The findings suggest that more perceived support from family, appropriately perceived support from friends, higher levels of resilience, and less loneliness all play important roles in preventing adolescent PSMU.

References

Abi-Jaoude, E., Naylor, K. T., & Pignatiello, A. (2020). Smartphones, social media use and youth mental health. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 192(6), E136–E141. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.190434

Alimoradi, Z., Lin, C. Y., Imani, V., Griffiths, M. D., & Pakpour, A. H. (2019). Social media addiction and sexual dysfunction among Iranian women: The mediating role of intimacy and social support. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(2), 318–325. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.24

Andreassen, C. S. (2015). Online social network site addiction: A comprehensive review. Current Addiction Reports, 2(2), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0056-9

Andreassen, C. S., Pallesen, S., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 287–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006

Antheunis, M. L., Schouten, A. P., & Krahmer, E. (2016). The role of social networking sites in early adolescents’ social lives. Journal of Early Adolescence, 36(3), 348–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431614564060

Arimoto, A., & Tadaka, E. (2019). Reliability and validity of Japanese versions of the UCLA loneliness scale version 3 for use among mothers with infants and toddlers: A cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health, 19(1), 105. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-019-0792-4

Arslan, G. (2016). Psychological maltreatment, emotional and behavioral problems in adolescents: The mediating role of resilience and self-esteem. Child Abuse & Neglect, 52, 200–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.09.010

Badenes-Ribera, L., Fabris, M. A., Gastaldi, F. G. M., Prino, L. E., & Longobardi, C. (2019). Parent and peer attachment as predictors of Facebook addiction symptoms in different developmental stages (early adolescents and adolescents). Addictive Behaviors, 95, 226–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.05.009

Bo, A., Hai, A. H., & Jaccard, J. (2018). Parent-based interventions on adolescent alcohol use outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 191, 98–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.05.031

Brand, M., Wegmann, E., Stark, R., Müller, A., Wölfling, K., Robbins, T. W., & Potenza, M. N. (2019). The Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: Update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond Internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 104, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.06.032

Brand, M., Young, K. S., Laier, C., Wölfling, K., & Potenza, M. N. (2016). Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: An Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 71, 252–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.033

Canale, N., Marino, C., Griffiths, M. D., Scacchi, L., Monaci, M. G., & Vieno, A. (2019). The association between problematic online gaming and perceived stress: The moderating effect of psychological resilience. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(1), 174–180. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.01

Casale, S., Fioravanti, G., Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2014). From socially prescribed perfectionism to problematic use of internet communicative services: The mediating roles of perceived social support and the fear of negative evaluation. Addictive Behaviors, 39(12), 1816–1822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.06.006

Cauberghe, V., Van Wesenbeeck, I., De Jans, S., Hudders, L., & Ponnet, K. (2021). How adolescents use social media to cope with feelings of loneliness and anxiety during COVID-19 lockdown. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 24(4), 250–257. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0478

CNNIC. (2020). The 45th statistical survey report on the internet development in China. Available at: http://www.cac.gov.cn/2020-04/27/c_1589535470378587.htm

Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113

Corsano, P., Musetti, A., Caricati, L., & Magnani, B. (2017). Keeping secrets from friends: Exploring the effects of friendship quality, loneliness and self-esteem on secrecy. Journal of Adolescence, 58, 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.04.010

Drouin, M., McDaniel, B. T., Pater, J., & Toscos, T. (2020). How parents and their children used social media and technology at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and associations with anxiety. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 23(11), 727–736. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0284

El Rawas, R., Amaral, I. M., & Hofer, A. (2020). Social interaction reward: A resilience approach to overcome vulnerability to drugs of abuse. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 37, 12–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.06.008

Fergus, S., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26, 399–419. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357

Geurts, S. M., Koning, I. M., Vossen, H. G. M., & van den Eijnden, R. J. J. M. (2022). Rules, role models or overall climate at home? Relative associations of different family aspects with adolescents’ problematic social media use. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 116, 152318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2022.152318

Goldstein, A. L., Faulkner, B., & Wekerle, C. (2013). The relationship among internal resilience, smoking, alcohol use, and depression symptoms in emerging adults transitioning out of child welfare. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(1), 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.08.007

Gong, Y., Shi, J., Ding, H., Zhang, M., Kang, C., Wang, K., Yu, Y., Wei, J., Wang, S., Shao, N., & Han, J. (2020). Personality traits and depressive symptoms: The moderating and mediating effects of resilience in Chinese adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 265, 611–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.102

Griffiths, M. D. (2005). A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10(4), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890500114359

Gunuc, S., & Dogan, A. (2013). The relationships between Turkish adolescents’ Internet addiction, their perceived social support and family activities. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2197–2207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.04.011

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Haythornthwaite, C. (2002). Strong, weak, and latent ties and the impact of new media. The Information Society, 18, 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972240290108195

Haythornthwaite, C. (2005). Social networks and Internet connectivity effects. Information, Communication & Society, 8, 125–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691180500146185

He, N., & Xiang, Y. (2022). Child maltreatment and nonsuicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: The mediating effect of psychological resilience and loneliness. Children and Youth Services Review, 133, 106335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106335

Heffer, T., Good, M., Daly, O., MacDonell, E., & Willoughby, T. (2019). The longitudinal association between social-media use and depressive symptoms among adolescents and young adults: An empirical reply to Twenge et al. (2018). Clinical Psychological Science, 7(3), 462–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702618812727

Horzum, M. B. (2016). Examining the relationship to gender and personality on the purpose of Facebook usage of Turkish university students. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 319–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.010

Hou, X., Wang, H., Guo, C., Gaskin, J., Rost, D. H., & Wang, J. (2017). Psychological resilience can help combat the effect of stress on problematic social networking site usage. Personality and Individual Differences, 109, 61–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.12.048

Huang, C. (2022). A meta-analysis of the problematic social media use and mental health. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 68(1), 12–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020978434

Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Hardcastle, K. A., Sethi, D., Butchart, A., Mikton, C., Jones, L., & Dunne, M. P. (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Public Health, 2(8), e356–e366. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4

Jiang, Y. Z. (2018). Development of problematic mobile social media usage assessment questionnaire for adolescents. Psychology: Techniques and Application, 6(10), 613–621. https://doi.org/10.16842/j.cnki.issn2095-5588.2018.10.004

Jin, L., Hao, Z., Huang, J., Akram, H. R., Saeed, M. F., & Ma, H. (2021). Depression and anxiety symptoms are associated with problematic smartphone use under the COVID-19 epidemic: The mediation models. Children and Youth Services Review, 121, 105875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105875

Kapıkıran, Ş. (2013). Loneliness and life satisfaction in Turkish early adolescents: The mediating role of self esteem and social support. Social Indicators Research, 111(2), 617–632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0024-x

Katja, K., Marina, H., Urška, A., Nina, J., & Sara, T. (2016). Does being on Facebook make me (feel) accepted in the classroom? The relationships between early adolescents’ Facebook usage, classroom peer acceptance and self-concept. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 375–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.04.013

Kırcaburun, K., Kokkinos, C. M., Demetrovics, Z., Király, O., Griffiths, M. D., & Çolak, T. S. (2019). Problematic online behaviors among adolescents and emerging adults: Associations between cyberbullying perpetration, problematic social media use, and psychosocial factors. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(4), 891–908. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9894-8

Kong, F., & You, X. (2013). Loneliness and self-esteem as mediators between social support and life satisfaction in late adolescence. Social Indicators Research, 110(1), 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9930-6

Lasgaard, M. (2007). Reliability and validity of the Danish version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(7), 1359–1366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.10.013

Ledbetter, A. M., Mazer, J. P., DeGroot, J. M., Meyer, K. R., Mao, Y., & Swafford, B. (2011). Attitudes toward online social connection and self-disclosure as predictors of Facebook communication and relational closeness. Communication Research, 38, 27–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650210365537

Ledbetter, A. M., Taylor, S. H., & Mazer, J. P. (2016). Enjoyment fosters media use frequency and determines its relational outcomes: Toward a synthesis of uses and gratifications theory and media multiplexity theory. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.053

Lin, C. Y., Namdar, P., Griffiths, M. D., & Pakpour, A. H. (2021). Mediated roles of generalized trust and perceived social support in the effects of problematic social media use on mental health: A cross-sectional study. Health Expectations, 24(1), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13169

Liu, C., & Ma, J. (2020). Social support through online social networking sites and addiction among college students: The mediating roles of fear of missing out and problematic smartphone use. Current Psychology, 39(6), 1892–1899. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-0075-5

Lutha, S. S., & Cicchetti, D. (2000). The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Development and Psychopathology, 12(4), 857–885. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579400004156

Marengo, D., Angelo Fabris, M., Longobardi, C., & Settanni, M. (2022). Smartphone and social media use contributed to individual tendencies towards social media addiction in Italian adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Addictive Behaviors, 126, 107204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107204

Mcdonald, M., Mccormack, D., Avdagic, E., Hayes, L., & Dakin, P. (2019). Understanding resilience: Similarities and differences in the perceptions of children, parents and practitioners. Children and Youth Services Review, 99, 270–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.01.016

McDougall, M. A., Walsh, M., Wattier, K., Knigge, R., Miller, L., Stevermer, M., & Fogas, B. S. (2016). The effect of social networking sites on the relationship between perceived social support and depression. Psychiatry Research, 246, 223–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.09.018

Meshi, D., & Ellithorpe, M. E. (2021). Problematic social media use and social support received in real–life versus on social media: Associations with depression, anxiety and social isolation. Addictive Behaviors, 119, 106949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106949

Navarro, R., Yubero, S., & Larranaga, E. (2018). Cyberbullying victimization and fatalism in adolescence: Resilience as a moderator. Children and Youth Services Review, 84, 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.12.011

O'Keeffe, G. S., Clarke-Pearson, K., & Council, O. C. A. M. (2011). The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics, 127(4), 800–804. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-0054

Oliveira, M. J. D., Huertas, M. K. Z., & Lin, Z. (2016). Factors driving young users’ engagement with Facebook: Evidence from Brazil. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 54–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.038

Ouyang, C., Li, D., Li, X., Xiao, J., Sun, W., & Wang, Y. (2020). Cyber victimization and tobacco and alcohol use among adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Children and Youth Services Review, 114, 105041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105041

Peris, T. S., Thamrin, H., & Rozenman, M. S. (2021). Family intervention for child and adolescent anxiety: A meta–analytic review of therapy targets, techniques, and outcomes. Journal of Affective Disorders, 286, 282–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.053

Perlman, D., & Peplau, L. A. (1981). Toward a social psychology of loneliness. Personal Relationships, 3, 31–56.

Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., Harris, R., Van Roekel, E., Lodder, G., Bangee, M., Maes, M., & Verhagen, M. (2015). Loneliness across the life span. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 250–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615568999

Reissmann, A., Hauser, J., Stollberg, E., Kaunzinger, I., & Lange, K. W. (2018). The role of loneliness in emerging adults’ everyday use of Facebook-An experience sampling approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 88, 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.06.011

Reuben, N., Rebecca, P. A., & Moon-Ho, R. H. (2012). Coping with anxiety, depression, anger and aggression: The mediational role of resilience in adolescents. Child & Youth Care Forum, 41(6), 529–546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-012-9182-x

Rew, L., Taylor Seehafer, M., Thomas, N. Y., & Yockey, R. D. (2001). Correlates of resilience in homeless adolescents. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 33(1), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00033.x

Ronen, T., Hamama, L., Rosenbaum, M., & Mishely-Yarlap, A. (2016). Subjective well-being in adolescence: The role of self-control, social support, age, gender, and familial crisis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(1), 81–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9585-5

Rousseau, A., Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2019). The reciprocal relations between Facebook relationship maintenance behaviors and adolescents’ closeness to friends. Journal of Adolescence, 76, 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.09.001

Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., Pyun, Y., Aycock, C., & Coyle, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 142(10), 1017–1067. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000058

Rutter, M. (2013). Annual research review: Resilience-clinical implications. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 54(4), 474–487. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02615.x

Ryan, T., Chester, A., Reece, J., & Xenos, S. (2014). The uses and abuses of Facebook: A review of Facebook addiction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3(3), 133–148.

Sage, M., Randolph, K., Fitch, D., & Sage, T. (2021). Internet use and resilience in adolescents: A systematic review. Research on Social Work Practice, 31(2), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731520967409

Sampasa-Kanyinga, H., Colman, I., Goldfield, G. S., Hamilton, H. A., & Chaput, J. P. (2020). Sex differences in the relationship between social media use, short sleep duration, and body mass index among adolescents. Sleep Health, 6(5), 601–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2020.01.017

Sampasa-Kanyinga, H., Goldfield, G. S., Kingsbury, M., Clayborne, Z., & Colman, I. (2020). Social media use and parent-child relationship: A cross-sectional study of adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology, 48(3), 793–803. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22293

Sampasa-Kanyinga, H., & Lewis, R. F. (2015). Frequent use of social networking sites is associated with poor psychological functioning among children and adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 18(7), 380–385. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0055

Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Sidani, J. E., Bowman, N. D., Marshal, M. P., & Primack, B. A. (2017). Problematic social media use and depressive symptoms among U.S. young adults: A nationally-representative study. Social Science & Medicine, 182, 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.061

Shensa, A., Sidani, J. E., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Switzer, G. E., Primack, B. A., & Choukas-Bradley, S. (2020). Emotional support from social media and face-to-face relationships: Associations with depression risk among young adults. Journal of Affective Disorders, 260, 38–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.092

Smock, A. D., Ellison, N. B., Lampe, C., & Wohn, D. Y. (2011). Facebook as a toolkit: A uses and gratification approach to unbundling feature use. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(6), 2322–2329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.07.011

Song, H., Zmyslinski-Seelig, A., Kim, J., Drent, A., Victor, A., Omori, K., & Allen, M. (2014). Does Facebook make you lonely? A meta analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 446–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.011

Stockdale, L. A., & Coyne, S. M. (2020). Bored and online: Reasons for using social media, problematic social networking site use, and behavioral outcomes across the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescence, 79, 173–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.01.010

Sundar, S. S., & Limperos, A. M. (2013). Uses and grats 2.0: New gratifications for new media. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 57(4), 504–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2013.845827

Süral, I., Griffiths, M. D., Kircaburun, K., & Emirtekin, E. (2019). Trait emotional intelligence and problematic social media use among adults: The mediating role of social media use motives. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(2), 336–345.

Tandon, A., Kaur, P., Dhir, A., & Mäntymäki, M. (2020). Sleepless due to social media? Investigating problematic sleep due to social media and social media sleep hygiene. Computers in Human Behavior, 113, 106487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106487

Tu, Y., & Zhang, S. (2015). Loneliness and subjective well–being among Chinese undergraduates: The mediating role of self–efficacy. Social Indicators Research, 124(3), 963–980. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0809-1

Turel, O., & Qahri-Saremi, H. (2016). Problematic use of social networking sites: Antecedents and consequence from a dual-system theory perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 33(4), 1087–1116. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2016.1267529

Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2007). Preadolescents’ and adolescents’ online communication and their closeness to friends. Developmental Psychology, 43(2), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.267

Vannucci, A., Simpson, E. G., Gagnon, S., & Ohannessian, C. M. (2020). Social media use and risky behaviors in adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 79, 258–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.01.014

Walburg, V., Mialhes, A., & Moncla, D. (2016). Does school-related burnout influence problematic Facebook use? Children and Youth Services Review, 61, 327–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.01.009

Wang, K., Frison, E., Eggermont, S., & Vandenbosch, L. (2018). Active public Facebook use and adolescents’ feelings of loneliness: Evidence for a curvilinear relationship. Journal of Adolescence, 67, 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.05.008

Wegmann, E., Brandtner, A., & Brand, M. (2021). Perceived strain due to COVID-19-related restrictions mediates the effect of social needs and fear of missing out on the risk of a problematic use of social networks. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 623099. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.623099

Weiland, B. J., Nigg, J. T., Welsh, R. C., Yau, W. Y., Zubieta, J. K., Zucker, R. A., & Heitzeg, M. M. (2012). Resiliency in adolescents at high risk for substance abuse: Flexible adaptation via subthalamic nucleus and linkage to drinking and drug use in early adulthood. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 36(8), 1355–1364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01741.x

Winemiller, D. R., Mitchell, M. E., Sutliff, J., & Cline, D. J. (1993). Measurement strategies in social support: A descriptive review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 49(5), 638–648. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(199309)49:5%3C638::aid-jclp2270490505%3E3.0.co;2-7

Xiao, L., & Mou, J. (2019). Social media fatigue-Technological antecedents and the moderating roles of personality traits: The case of WeChat. Computers in Human Behavior, 101, 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.001

Yu, X., Lau, J. T. F., Mak, W. W. S., Zhang, J., Lui, W. W. S., & Zhang, J. (2011). Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale among Chinese adolescents. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 52(2), 218–224. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.05.010

Yu, X., & Zhang, J. (2007). Factor analysis and psychometric evaluation of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD–RISC) with Chinese people. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 35(1), 19–30. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.2224/sbp.2007.35.1.19

Zhang, H., Han, T., Ma, S., Qu, G., Zhao, T., Ding, X., Sun, L., Qin, Q., Chen, M., & Sun, Y. (2022). Association of child maltreatment and bullying victimization among Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of family function, resilience, and anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders, 299, 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.11.053

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52, 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32200864), the Ministry of Education in China (MOE) Project of Humanities and Social Sciences (21YJC190005), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (CCNU22QN020), the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province of China (2020CFB363), and the Open Research Fund of the Key Laboratory of Adolescent Cyberpsychology and Behavior (CCNU) (2019A01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of university’s Research Ethics Board and with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, S., Yuan, Z., Niu, G. et al. Family Matters More Than Friends on Problematic Social Media Use Among Adolescents: Mediating Roles of Resilience and Loneliness. Int J Ment Health Addiction (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01026-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01026-w