Abstract

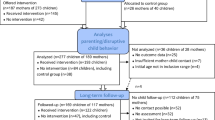

Based on evidence that early antisocial behavior is a key risk factor for delinquency and crime throughout the life course, early family/parent training, among its many functions, has been advanced as an important intervention/prevention effort. There are several theories concerning why early family/parent training may cause a reduction in child behavior problems including antisocial behavior and delinquency (and have other ancillary benefits in non-crime domains over the life course). The prevention of behavior problems is one of the many objectives of early family/parent training, and it comprises the main focus of this review. Results indicate that early family/parent training is an effective intervention for reducing behavior problems among young children, and the weighted effect size was 0.35. The results from a series of analog to the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and weighted least squares regression models (with random effects) demonstrated that there were significant differences in the effect sizes of studies conducted in the USA versus those conducted in other countries and that studies that were based on samples smaller than 100 children had larger effect sizes. Sample size was also the strongest predictor of the variation in the effect sizes. Additional evidence indicated that early family/parent training was also effective in reducing delinquency and crime in later adolescence and adulthood. Overall, the findings lend support for the continued use of early family/parent training to prevent behavior problems. Future research should test the main theories of early family/parent training and detail more explicitly the causal mechanisms by which early family/parent training reduces delinquency and crime, and future evaluations should employ high quality designs with long-term follow-ups, including repeated measures of antisocial behavior, delinquency, and crime over the life course.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It is useful to define what parent training is and is not. There are two general subcategories that deal with prevention programs for early childhood, based on their general approach (Greenwood 2006: 52). The first, home visitation, includes those programs for mothers with infants, with or without additional services. According to Greenwood (2006: 52), these programs “work with at-risk mothers to improve their prenatal health status, reduce birth complications, and provide guidance and support in caring for the infant and improving the quality of their own lives. Programs differ in how they identify at-risk mothers, when the home visits begin and end, who the visitors are, what the visits cover, and what other services are provided.” The main goal of home visiting programs centers on educating parents to improve the life chances of infants and children. According to Farrington and Welsh (2007: 123), “Some of the main goals include the prevention of preterm or low-weight births, the promotion of healthy child development or school readiness, and the prevention of child abuse and neglect. Home visits very often also serve to improve parental well-being, linking parents to community resources to help with employment, educational, or addiction recovery.” The second subcategory includes those programs that combine parent training, daycare, and preschool for parents with preschool children. According to Greenwood (2006: 54), these programs “attempt to advance cognitive and social development of the children, as well as the parenting skills of their caregivers, so that participants will be better prepared and more successful when they enter regular school. Some programs include home visits as well.” According to Farrington and Welsh (2007: 125), “[D]aycare programs are distinguished from preschool programs, in that the daycare programs are not focused on the child’s intellectual enrichment or necessarily on readying the child for kindergarten and elementary school, but serve largely as an organized form of daycare to allow for parents (especially mothers) to return to work. Daycare also provides children with a number of important benefits, including social interaction with other children and stimulation of their cognitive, sensory, and motor control skills.” Another set of programs within this subcategory include parent management training programs, which refer to treatment procedures in which parents are trained to alter their child’s behavior at home (Farrington and Welsh 2007: 126). Many are based on the behavioral parent management training theory of Patterson (1982).

Those authors did not conduct an exhaustive review, as they did not search major abstracting services such as PSYCHINFO, which would have, using general search terms, identified a great many more studies than they likely identified through their process.

Specifically, the family and family factors were the focus of the intervention, and programs that targeted only the child were excluded from their review.

Several reasons could account for these findings, including the heterogeneity in the definition of parent training, the absence of evidence regarding which components of parent training were most effective, the small number of findings, the lack of consistency in outcomes (delinquency) assessed, which intervention components were most important, which parents were more likely to benefit from the intervention, how long it should last, and whether parent training should be combined with other interventions (pp. 28-29).

Greenwood also reviewed programs for elementary-school-age children, two of which included young children aged 5-10 years (FAST TRACK, which adopts social skills and parent training, home visits, tutoring, and behavior management) and 3-8 years (The Incredible Years, which adopts parent training and behavior management), respectively. Greenwood identifies each as a program that ‘works’

Greenwood (2006: 82) notes that, while the positive effects do not appear when the nurses are absent from the program implementation, NFP is being replicated in more than 60 sites and has been evaluated in three randomized trials. Expansion of the program must follow a very strict set of guidelines and protocols. Further, a competitor of NFP, Healthy Families America (HFA) is seeking to expand home visitation services in the USA.

The majority of the studies included in this meta-analysis utilized some type of parent training program, which typically involved either individual or group-based parent training sessions that were conducted in a clinic, the school, or some other type of community-based site, and the main parenting intervention programs were the Incredible Years Parenting Program, the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program, and parent–child interaction therapy. Comparatively, the home visitation studies typically involved health professionals, such as nurses or doctors, or paraprofessionals that visited the mothers and gave them advice about how to manage their child’s behavior effectively. All the early family/parent training interventions (as defined) in these studies had begun prior to childbirth or early in infancy.

We certainly recognize that studies are likely to vary in how they operationalize and report child behavior problems; however, in order to provide a more general portrait of the totality of the effects, we opted to rely on self-report measures from a variety of psychometric indexes that are commonly used in studies such as these [e.g., child behavior checklist (CBCL) and Eyberg child behavior inventory (ECBI)]. Yet, a note of caution is needed here. We also acknowledge that particular indexes are often reported as a total behavioral measure (e.g., include internalizing and externalizing behaviors) and that less frequently do the studies themselves disaggregate their child behavior construct (i.e., report separate effects for externalizing, internalizing, aggression, hostility, etc.). Ultimately, we decided to utilize the overall behavioral measure, since we were primarily concerned with the totality of the effects. Nevertheless, we call for future research on this issue in order to partial out the possible variation in the effects of early family/parent training programs on certain dimensions and subscales within the larger construct of child behavior problems, including delinquency and antisocial behavior.

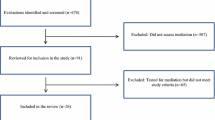

The key words included: “parent training” and “childhood” or “pre-school” and “delinquency” or “conduct disorder” or “antisocial behavior” or “aggression” or “physical aggression” or “behavior problems”, and “family training” and “childhood” or “pre-school” and “delinquency” or “conduct disorder” or “antisocial behavior” or “aggression” or “physical aggression” or “behavior problems”.

The databases included: Criminal Justice Periodical Index, Criminal Justice Abstracts, National Criminal Justice Reference Services (NCJRS) Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, Social Science Abstracts (SocialSciAbs), Social Science Citation Index, Dissertation Abstracts, Government Publications Office, Monthly Catalog (GPO Monthly), PsychINFO, C2 SPECTR (The Campbell Collaboration Social, Psychological, Educational and Criminological Trials Register), Australian Criminology Database (CINCH), MEDLINE, Web of Knowledge, IBSS (International Bibliography of the Social Sciences, and Future of Children (publications).

These journals included: Criminology, Criminology and Public Policy, Justice Quarterly, Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, Journal of Criminal Justice, Police Quarterly, Policing, Police Practice and Research, British Journal of Criminology, Journal of Quantitative Criminology, Crime and Delinquency, Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, Policing and Society, as well as psychology/psychiatry journals, including, among others, Child Development.

The groups and agencies included: Washington State Institute for Public Policy, Institute for Law and Justice, Vera Institute for Justice, Rand Corporation, The Home Office (UK), Australian Institute of Criminology, Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention, Cochrane Library, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA), Institute of Medicine, American Psychiatric Association, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP), Youth Justice Board, Department of Health and Department of Children, Schools, and Families (UK), National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), UK, and National Children’s Bureau (which publishes ‘Child Data Abstracts’).

Another possible way to pool ESs across interventions that use multiple groups who receive variations of the treatment is to average the mean and variance pooled across the treatment groups and compare this pooled mean and variance with the control group, as opposed to generating independent ESs for each treatment group compared with the control group and then averaging these effect sizes. We recalculated the single study ESs using this alternative procedure, and the results were substantively similar to those presented in the text.

While studies do not always report actual percentages of dropouts and the specific reasons for attrition (e.g., death, dropout, loss of contact), we still estimated the correlation between dropout rates and ES, based on subtracting the sample size that provided data after assessment from the original sample size reported at the onset of the program and divided this difference by the original sample size. According to estimates derived from Lipsey and Wilson’s (2001) meta-analysis regression macro, the correlation between dropout rates and ES was positive (r = 0.12), indicating that studies having larger attrition tended to have larger ESs; however, the correlation was non-significant (P = 0.31).

The sample sizes of the studies in this review ranged from a low of 11 (Zangwill 1983) to a high of 870 (McCarton et al. 1997). On average, the sample size was 137 [standard deviation ((SD) = 184.15], and a little over a third of the studies had sample sizes of fewer than 50, and 10% of the studies had samples > n = 25.

The one study with the worst effect size (−0.97) was by Helfenbaum-Kun and Ortiz (2007), but it is worth noting that this effect was only based on the fathers’ reports, because there was not enough information on how many mothers had participated in providing data for the child outcome measures.

In order to determine if any outliers were having a substantial impact on the mean ES, we removed the three outliers that had individual ESs greater than two standard deviations from the mean ES and re-estimated the mean ES with the remaining 52 studies. Since the mean ES after we had removed the outliers was reduced to 0.32 (ci = 0.24–0.40), we retained the outliers, since they did not appear to have had a large effect on the mean ES.

The correlations were based on the regression coefficient estimated with Lipsey and Wilson’s SPSS meta-analysis regression macro using a single predictor.

It is important to note here that, while our overall ES generated per study was based on one ES per study, in this particular portion of the analysis we performed a moderator analysis of source (reports by parents, teachers, and direct observers) and included only one effect size per dataset in each category of the moderator variable (that is, only one effect based on parents’ report, etc.) but allowed a study to provide an ES to more than one category when available (that is, we included both a parent and teacher report from the same study). Performing the analysis in this fashion estimates the bias in the test of the difference across the mean ESs in a known direction, e.g., the P value will be somewhat too big. Thus, if a statistically significant effect is found, then there is confidence that a ‘correctly’ estimated model would have also been significant.

Separate weighted least squares regression models (with random effects) were also estimated for the small and large sample studies. These findings failed to reveal anything different from what had already been demonstrated in the full sample model (i.e., the marginal significance of being a US-based study).

References

Abbott-Shim, M., Lambert, R., & McCarty, F. (2003). A comparison of school readiness outcomes for children randomly assigned to a head start program and the program’s wait list. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 8, 191–214.

Aos, S., Lieb, R., Mayfield, J., Miller, M., & Pennuci, A. (2004). Benefits and costs of prevention and early intervention programs for youth. Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy.

Aos, S., Miller, M., & Drake, E. (2006). Evidence-based public policy options to reduce future prison construction, criminal justice costs, and crime rates. Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy.

Aos, S., Phipps, P., Barnoski, R., & Lieb, R. (2001). The comparative costs and benefits of programs to reduce crime. Olympia: Washington Institute for Public Policy.

Barkley, R. A., Shelton, T. L., Crosswait, C., Moorehouse, M., Fletcher, K., Barrett, S., et al. (2000). Multimethod psychoeducational intervention for preschool children with disruptive behavior: Two-year post-treatment follow-up. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 319–332.

Baydar, N., Reid, M. J., & Webster-Stratton, C. (2003). The role of mental health factors and program engagement in the effectiveness of a preventative parenting program for Head Start mothers. Child Development, 74, 1433–1453.

Bernazzani, O., & Tremblay, R. E. (2006). Early parent training. In B. C. Welsh, & D. P. Farrington (Eds.), Preventing crime: What works for children, offenders, victims, and places. Dordrecht: Springer.

Bernazzani, O., Cote, C., & Tremblay, R. E. (2001). Early parent training to prevent disruptive behavior problems and delinquency in children. ANNALS, 578, 90–103.

Bilukha, O., Hahn, R. A., Crosby, A., et al. (2005). The effectiveness of early childhood home visitation in prevention violence: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28, 11–39.

Bor, W., Sanders, M. R., & Markie-Dadds, C. (2002). The effects of the Triple P-Positive Parenting program on preschool children with co-occurring disruptive behavior and attention/hyperactive difficulties. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30, 571–587.

Borenstein, M. (2005). Software for publication bias. In H. R. Rothstein, A. J. Sutton, & M. Borenstein (eds.), Publication bias in meta-analysis: Prevention, assessment, and adjustments. John Wiley & Sons.

Bradley, S. J., Jadaa, D. A., Brody, J., Landy, S., Tallett, S. E., Watson, W., et al. (2003). Brief psychoeducational parenting program: An evaluation and 1-year follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychology, 42, 1171–1178.

Brestan, E. V., Eyberg, S. M., Boggs, S. R., & Algina, J. (1997). Parent–child interaction therapy: Parents’ perceptions of untreated siblings. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 19, 13–28.

Brooks-Gunn, J., McCarton, C., McCormick, M., et al. (1994). Early intervention in low-birth-weight premature infants: Results through age 5 years from the Infant Health and Development Program. Journal of the American Medical Association, 272, 1257–1262.

Butz, A. M., Pulsifer, M., Marano, N., Belcher, H., Lears, M. K., & Royall, R. (2001). Effectiveness of a home intervention for perceived child behavioral problems and parenting stress in children with in utero drug exposure. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 155, 1029–1037.

Calonge, N. (2005). Community interventions to prevent violence: Translation into public health practice. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(2S1), 4–5.

Connell, S., Sanders, M. R., & Markie-Dadds, C. (1997). Self-directed behavioral family intervention for parents of oppositional children in rural and remote areas. Behavior Modification, 21, 379–408.

Cullen, K. J. (1976). A six year controlled trial of prevention of children’s behaviour disorders. Journal of Paediatrics, 88, 662–666.

Cullen, K. J., & Cullen, A. M. (1996). Long-term follow-up of the Busselton six-year controlled trial of prevention of children’s behavior disorders. Journal of Pediatrics, 29, 136–139.

Cunningham, C. E., Bremner, R., & Boyle, M. (1995). Large group community-based parenting programs for families of preschoolers at risk for disruptive behaviour disorders: Utilization, cost effectiveness, and outcome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 36, 1141–1159.

Dickens, W. T., & Baschnagel, C. (2008). Dynamic Estimates of the Fiscal Effects of Investing in Early Childhood Programs. Partnership For America’s Economic Success. Washington, DC: The Pew Foundation.

Dush, D., Hirt, M., & Schroeder, H. (1989). Self-statement modification in the treatment of child behavior disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 106, 97–106.

Edwards, R. T., Céilleachair, A., Bywater, T., Hughes, D. A., & Hutchings, J. (2007). Parenting programme for parents of children at risk of developing conduct disorder: Cost effectiveness analysis. British Medical Journal, 334, 682–685.

Eppley, K., Abrams, A., & Shear, J. (1989). Differential effects of relaxation techniques on trait anxiety: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45, 957–974.

Eyberg, S. M., Boggs, S. R., & Algina, J. (1995). New developments in psychosocial, pharmacological, and combined treatments of conduct disorders in aggressive children. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 31, 83–91.

Fanning, J. L. (2007). Parent training for caregivers of typically developing, economically disadvantaged preschoolers: An initial study in enchancing language developement, avoiding behavior problems, and regulating family stress. unpublised dissertion, University at Oregon.

Farnworth, M., Schweinhart, L. J., & Berrueta-Clement, J. R. (1985). Preschool intervention, school success and delinquency in a high-risk sample of youth. American Educational Review Journal, 22, 445–464.

Farrington, D. P., & Welsh, B. C. (2003). Family-based prevention of offending: A meta-analysis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 36, 127–151.

Farrington, D. P., & Welsh, B. C. (2007). Saving children from a life of crime: Early risk factors and effective interventions. New York: Oxford University Press.

Feinfield, K. A., & Baker, B. L. (2004). Empirical support for a treatment program for families of young children with externalizing problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 182–195.

Fergusson, D. M., Grant, H., Horwood, L. J., & Ridder, E. M. (2005a). Randomized trial of the Early Start Program of home visitation. Pediatrics, 116, 803–809.

Fergusson, D., Horwood, J., Ridder, E., & Grant, H. (2005b). Early Start: Evaluation report. Christchurch, New Zealand.

Foster, E. M., Olchowski, A., & Webster-Stratton, C. (2007). Is stacking intervention components cost-effective? An analysis of the Incredible Years program. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46, 1414–1424.

Frick, P. J., & Loney, B. R. (1999). Outcomes of children and adolescents with oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. In H. C. Quay, & A. E. Hogan (Eds.), Handbook of disruptive behavior disorders. New York: Kluwer.

Gardner, F., Burton, J., & Klimes, I. (2006). Randomised controlled trial of a parenting intervention in the voluntary sector for reducing child conduct problems: outcomes and mechanisms of change. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 1123–1132.

Gomby, D. S., Culross, P. L., & Behrman, R. E. (1999). Home visiting: Recent program evaluations—analysis and recommendations. Future of Children, 9, 4–26.

Greenwood, P. W. (2006). Changing lives: Delinquency prevention as crime-control policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Greenwood, P. W., Wasserman, J., Davis, L. M., Flora, J. A., Howard, K. A., Schleicher, N., et al. (2001). The California Wellness Foundation’s Violence Prevention Initiative. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

Gross, D., Fogg, L., & Tucker, S. (1995). The efficacy of parent training for promoting positive parent-toddler relationships. Research in Nursing and Health, 18, 489–499.

Hamilton, S. B., & MacQuiddy, S. L. (1984). Self-administered behavioral parent training: Enhancement of treatment efficacy using a time-out signal seat. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 13, 61–69.

Hawkins, J. D., Catalano, R. F., Kosterman, R., Abbott, R., & Hill, K. G. (1999). Preventing adolescent health-risk behaviors by strengthening protection during childhood. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 153, 226–234.

Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. New York: Academic Press.

Heinicke, C. M., Fineman, N. R., Ponce, V. A., & Guthrie, D. (2001). Relation-based intervention with at-risk mothers: Outcome in the second year of life. Infant Mental Health Journal, 22, 431–462.

Helfenbaum-Kun, E. D., & Ortiz, C. (2007). Parent-training groups for fathers of head start children: A pilot study of their feasibility and impact on child behavior and intra-familial relationships. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 29, 47–64.

Hembree-Kigin, T. L., & McNeil, C. B. (1995). Parent-child interaction therapy: A step-by-step guide for clinicians. New York: Plenum Press.

Hiscock, H., Bayer, J. K., Price, , Ukoumunne, O. C., Rogers, S., & Wake, M. (2008). Universal parenting programme to prevent early childhood behavioural problems: Cluster randomised trial. British Medical Journal, 336, 318–321.

Hutchings, J., Bywater, T., Daley, D., Gardner, F., Whitaker, C., Jones, K., et al. (2007). Parenting intervention in Sure Start services for children at risk of developing conduct disorder: Pragmatic randomized controlled trial. British Medical Journal, 334, 678–685.

Johnson, D. L. (2006). Parent-Child Development Center follow-up project: Child behavior problem results. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 27, 391–407.

Johnson, D. L., & Breckenridge, J. N. (1982). The Houston parent-child development center and the primary prevention of behavior problems in young children. American Journal of Community Psychology, 10, 305–316.

Johnson, D. L., & Walker, T. (1987). Primary prevention of behavior problems in Mexican-American children. American Journal of Community Psychology, 15, 375–385.

Jones, K., Daley, D., Hutchings, J., Bywater, T., & Eames, C. (2007). Efficacy of the Incredible Years Basic parent training programme as an early intervention for children with conduct problems and ADHD. Child: Care, Health, and Development, 33, 749–756.

Karoly, L., Greenwood, P., Everingham, S., Hoube, J., Kilburn, M., Rydell, C., et al. (2008). Inventing in our children: What we know and don’t know about the costs and benefits of early childhood intervention. RAND Report MR-898-TCWF.

Kazdin, A. E., Siegel, T. C., & Bass, D. (1992). Cognitive problem-solving skills training and parent management training in the treatment of antisocial behavior in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 733–747.

Kim, E., Cain, K. C., & Webster-Stratton, C. (2007). The preliminary effect of a parenting program for Korean American mothers: A randomized controlled experimental study.

Kim, E., Cain, K., & Webster-Stratton, C. (2008). The preliminary effect of a parenting program for Korean American mothers: A randomized controlled experimental study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 9, 1261–1273.

Kitzman, H., Olds, D. L., Henderson, C. R., et al. (1997). Effect of prenatal and infancy home visitation by nurses on pregnancy outcomes, childhood injuries, and repeated childbearing: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 278, 644–652.

Leung, C., Sanders, M. R., Leung, S., Mak, R., & Lau, J. (2003). An outcome evaluation of the implementation of the triple p-positive parenting program in Hong Kong. Family Process, 42, 531–544.

Lipsey, M., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Magnusson, K. A., & Duncan, G. J. (2004). Parent- versus child-based intervention strategies for promoting children’s well-being. In A. Kalil, & T. DeLeire (Eds.), Family investments in children’s potential: Resources and parenting behaviors that promote success (pp. 209–231). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Markie-Dadds, C., & Sanders, M. R. (2006). Self-directed triple p (positive parenting program) for mothers with children at-risk of developing. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 34, 259–275.

McCart, M. R., Priester, P. E., Davies, W. H., & Razia, A. (2006). Differential effectiveness of behavioral parent-training and cognitive behavioral therapy for antisocial youth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 34, 527–543.

McCarton, C. M., Brooks-Gunn, J., Wallace, I. F., et al. (1997). Results at age 8 years of early intervention for low-birth-weight premature infants: The Infant Health and Development Program. Journal of the American Medical Association, 277, 126–132.

McLeod, B. D., & Weisz, J. R. (2004). Using dissertations to examine potential bias in child and adolescent clinical trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 235–251.

McCord, J., Widom, C. S., & Crowell, N. E. (2001). Juvenile crime, juvenile justice. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

McCormick, M., Brooks-Gunn, J., Buka, S. L., et al. (2006). Early intervention in low birth weight premature infants: Results at 18 years of age for the Infant Health and Development Program. Pediatrics, 117, 771–780.

McNeil, C. B., Eyberg, S., Eisenstadt, T. H., Newcomb, K., & Funderburk, B. (1991). Parent–child interaction therapy with behavior problem children: Generalization of treatment effects to the school setting. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 20, 140–151.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). “Life-course-persistent” and “adolescence-limited” antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701.

Morawska, A., & Sanders, M. R. (2006). Self-administered behavioral family intervention for parents of toddlers: Part I. Efficacy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 10–19.

Mrazek, P. J., & Brown, C. H. (1999). An evidence-based literature review regarding outcomes in psychosocial prevention and early intervention in young children. Toronto: Invest in Kids Foundation.

Nagin, D. S. (2005). Group-based modeling of development. Cambridge, MA: University of Harvard Press.

Nagin, D. S., & Land, K. C. (1993). Age, criminal careers, and population heterogeneity: Specification and estimation of a nonparametric, mixed Poisson model. Criminology, 31, 327–362.

Nagin, D. S., & Tremblay, R. E. (2001). Analyzing developmental trajectories of distinct but related behaviors: A group-based method. Psychological Methods, 6, 18–34.

Nagin, D. S., Piquero, A. R., Scott, E., & Steinberg, L. (2006). Public preferences for rehabilitation versus incarceration of juvenile offenders: Evidence from a contingent valuation survey. Criminology & Public Policy, 5, 627–652.

Nicholson, B. C., Janz, P. C., & Fox, R. A. (1998). Evaluating a brief parental-education program for parents of young children. Psychological Reports, 82, 1107–1113.

Nicholson, B., Anderson, M., Fox, R., & Brenner, V. (2002). One family at a time: A prevention program for at-risk parents. Journal of Counseling and Development, 80, 362–372.

Olds, D., Henderson, C. R., Cole, R., et al. (1998). Long-term effects of nurse home visitation on children’s criminal and antisocial behavior: 15-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 280, 1238–1244.

Olds, D. L., Robinson, J., O’Brien, R., et al. (2002). Home visits by paraprofessionals and by nurses: A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics, 110, 486–496.

Olds, D. L., Kitzman, H., Cole, R., et al. (2004a). Effects of nurse home-visiting on maternal life-course and child development: Age 6 follow-up results of a randomized trial. Pediatrics, 114, 1550–1559.

Olds, D. L., Robinson, J., Pettitt, L., et al. (2004b). Effects of home visits by paraprofessionals and by nurses: Age 4 follow-up results of a randomized trial. Pediatrics, 114, 1560–1568.

Olds, D. L., Kitzman, H., Hanks, C., et al. (2007). Effects of nurse home visiting on maternal and child functioning: Age 9 follow-up of a randomized trial. Pediatrics, 120, e832–e845.

Patterson, G. R. (1982). Coercive family process. Eugene, OR: Castalia.

Patterson, J., Barlow, J., Mockford, C., Klimes, I., Pyper, C., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2002). Improving mental health through parenting programmes: Block randomised controlled trial. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 87, 472–477.

Piquero, A. R. (2008). Taking stock of developmental trajectories of criminal activity over the life course.. In A. Liberman (Ed.), The long view of crime: A synthesis of longitudinal research (Chapter 3). New York: Springer.

Piquero, A. R., Farrington, D. P., & Blumstein, A. (2003). “The criminal career paradigm.” In M. Tonry (Ed.), Crime and justice: A review of research, volume 30. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Reid, M. J., Webster-Stratton, C., & Beauchaine, T. P. (2001). Parent training in Head Start: A comparison of program response among African American, Asian American, Caucasian, and Hispanic mothers. Prevention Science, 2, 209–227.

Reid, M. J., Webster-Stratton, C., & Baydar, N. (2004). Halting the development of conduct problems in Head Start children. The effects of parent training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 33, 279–291.

Reid, M. J., Webster-Stratton, C., & Hammond, M. (2007). Enhancing a classroom social competence and problem-solving curriculum by offering parent training to families of moderate- to high-risk elementary school children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 36, 605–620.

Reynolds, A. J., Temple, J. A., Ou, S., Robertson, D. L., Mersky, J. P., Topitzes, J. W., et. al. (2007). Effects of a school-based, early childhood intervention on adult health and well-being. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 161, 730–739.

Reynolds, A. J., Temple, J. A., Robertson, D. L., & Mann, E. A. (2001). Long-term effects of an early childhood intervention on educational achievement and juvenile arrest: A 15-year follow-up of low-income children in public schools. Journal of the American Medical Association, 285, 2339–2346.

Robins, L. N. (1978). Sturdy childhood predictors of adult antisocial behaviour: Replications from longitudinal studies. Psychological Medicine, 8, 611–622.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1997). A life-course theory of cumulative disadvantage and the stability of delinquency. In T.P. Thornberry (Ed.), Developmental theories of crime and delinquency (pp. 131–161). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Sandy, S. V., & Boardman, S. K. (2000). The peaceful kids conflict resolution program. International Journal of Conflict Management, 11, 337–357.

Sanders, M. (1999). Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: Toward and empirically validated multilevel parenting and family support strategy for the prevention of behavior and emotional problems in children. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 2, 71–90.

Sanders, M. R., Markie-Dadds, C., Tully, L. A., & Bor, W. (2000a). The Triple P-Positive parenting program: A comparison of enhanced, standard, and self-directed behavioral family intervention for parents of children with early onset conduct problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 624–640.

Sanders, M. R., Montgomery, D. T., & Brechtman-Toussaint, M. L. (2000b). The mass media and the prevention of child behaviour problems: The evaluation of a television series to promote positive outcome for parents and their children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41, 939–948.

Schuhmann, E. M., Foote, R. C., Eyberg, S. M., Boggs, S. R., & Algina, J. (1998). Efficacy of parent-child interaction therapy: Interim report of a randomized trial with short-term maintenance. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 27, 34–45.

Schweinhart, L. J. (2007). Crime prevention by the High/Scope Perry Preschool program. Paper presented at the 2007 American Society of Criminology Conference. Atlanta, GA.

Schweinhart, L. J., & Xiang, Z. (2003). Evidence that the High/Scope Perry Preschool program prevents adult crime. Paper presented at the 2003 American Society of Criminology Conference. Denver, CO.

Schweinhart, L. J., Berrueta-Clement, J. R., Barnett, W. S., Epstein, A. S., & Weikart, D. P. (1985). Effects of the Perry Preschool program on youths through age 19: A summary. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 5, 26–35.

Schweinhart, L. J., Barnes, H. V., & Weikart, D. P. (1993). Significant benefits: The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study through age 27. Ypsilanti, MI: High/Scope Press.

Scott, S. (2002). Continuity of anti-social behaviour from age 5 to 17. Unpublished research for the UK Home Office cited (with diagram) in Sutton, C., Farrington, D.P. & Utting, D. (2004) Support from the Start. London: Dept. for Education and Skills. www.dfes.gov.uk/research/data/uploadfiles/RR524.pdf.

Scott, S., Spender, Q., Doolan, M., Jacobs, B., & Aspland, H. (2001). Multicentre controlled trial of parenting groups for childhood antisocial behaviour in clinical practice. British Medical Journal, 323, 194–197.

Serketich, W. J., & Dumas, J. E. (1996). The effectiveness of behavioral parent training to modify antisocial behavior in children: A meta-analysis. Behavior Therapy, 27, 171–186.

Shaw, D. S., Dishion, T. J., Supplee, L., Gardner, F., & Arnds, K. (2006). Randomized trial of a family-centered approach to the prevention of early conduct problems: 2-Year effects of the family check-up in early childhood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 1–9.

Sherman, Lawrence W., (Ed.). (2003). Misleading evidence and evidence-led policy: Making social science more experimental. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 589.

Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S., Daley, D., Thompson, M., Lavar-Bradbury, C., & Weeks, A. (2001). Parent-based therapies for preschool attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A randomized, controlled trial with a community sample. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40, 402–408.

Sterne, J. A., & Harbord, R. M. (2004). Funnel plots in meta analysis. Stata Journal, 4, 127–141.

Stone, W. L., Bendell, R. D., & Field, T. M. (1988). The impact of socioeconomic status on teenage mothers and children who received early intervention. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 9, 391–408.

Strayhorn, J. M., & Weidman, C. S. (1991). Follow-up one year after parent-child interaction training: Effects on behavior of preschool children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30, 138–143.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Taylor, T. K., Schmidt, F., Pepler, D., & Hodgins, H. (1998). A comparison of eclectic treatment with Webster-Stratton's parents and children series in a children's mental health center: A randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 29, 221–240.

Tremblay, R. E. (2000). The development of aggressive behavior during childhood: What have we learned in the past century? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 24, 129–141.

Tremblay, R. E., & Craig, W. M. (1995). “Developmental crime prevention.”. In M. Tonry, & D. P. Farrington (Eds.), Crime and justice: An annual review of research (Building a Safer Society: Strategic Approaches to Crime Prevention). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tremblay, R. E., LeMarquand, D., & Vitaro, F. (1999). “The prevention of oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder.” In H. C. Quay, & A. E. Hogan (Eds.), Handbook of disruptive behavior disorders. New York: Kluwer.

Tucker, S. J. (1996). The long-term efficacy of a behavioral parent training intervention for families with two-year olds. Chicago, IL: Unpublished dissertation, Rush University.

Tucker, S., Gross, D., Fogg, L., Delaney, K., & Lapporte, R. (1998). The long-term efficacy of a behavioral parent training intervention for families with 2-year-olds. Research in Nursing and Health, 21, 199–210.

Tulloch, E. A. (1997). Effectiveness of parent training on perception of parenting skill and reduction of preschool problem behaviors utilizing an ethnically diverse population. Unpublished dissertation, Hofstra University.

Van Zeijl, J., Mesman, J., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., et al. (2006). Attachment-based intervention for enhancing sensitive discipline in mothers of 1- to 3-year-old children at risk for externalizing behavior problems: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 994–1005.

Webster-Stratton, C. (1982). Teaching mothers through videotape modeling to change their children’s behavior. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 7, 279–294.

Webster-Stratton, C. (1984). Randomized trial of two parent-training programs for families with conduct-disordered children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 52, 666–678.

Webster-Stratton, C. (1990). Enhancing the effectiveness of self-administered videotape parent training for families with conduct-problem children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 18, 479–492.

Webster-Stratton, C. (1992). Individually administered videotape parent training: Who benefits? Cognitive Therapy and Research, 16, 31–35.

Webster-Stratton, C. (1998). Preventing conduct problems in Head Start children: Strengthening parent competencies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 715–730.

Webster-Stratton, C., & Hammond, M. (1997). Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: A comparison of child and parenting training interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 93–100.

Webster-Stratton, C., Kolpacoff, M., & Hollinsworth, T. (1988). Self-administered videotape therapy for families with conduct-problem children: Comparison with two cost-effective treatments and a control group. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 558–566.

Webster-Stratton, C., Reid, M. J., & Hammond, M. (2001). Preventing conduct problems, promoting social competence: A parent and teacher training partnership in Head Start. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30, 283–302.

Webster-Stratton, C., Reid, M. J., & Hammond, M. (2004). Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: Intervention outcomes for parent, child, and teacher training. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 105–124.

Zangwill, W. M. (1983). An evaluation of a parent training program. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 5, 1–16.

Acknowledgments

Support for this project was made possible by the Campbell Collaboration and the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (BRA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Piquero, A.R., Farrington, D.P., Welsh, B.C. et al. Effects of early family/parent training programs on antisocial behavior and delinquency. J Exp Criminol 5, 83–120 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-009-9072-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-009-9072-x