Abstract

Objectives

Early childhood poverty is associated with adult chronic diseases. The objectives of this study were to examine patterns of exposure to poverty during the first 10 years of life in the Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development (QLSCD) cohort according to three measures of poverty and to explore family characteristics associated with different poverty exposures.

Method

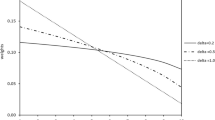

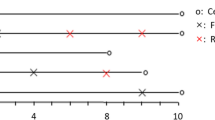

Data from 1,334 participants from the QLSCD were collected annually at home from ages 5 months through 10 years. Household income (previous 12 months) and sources of income were recorded at each data round. Poverty status was operationalized as 1) living below the low income cut-off of Statistics Canada, 2) receiving social welfare and 3) being in the lowest quintile of socio-economic status. We plotted trends in the prevalence of child poverty over time. We used latent class growth modelling to identify subgroups with similar poverty trajectories. Duration of poverty according to each measure was computed separately for early childhood, middle childhood, and the entire 10 years of life.

Results

Four trajectories of poverty were identified: stable poor, decreasing likelihood, increasing likelihood, and never poor. The three measures of poverty do not cover the same population, yet the characteristics of those identified as poor are similar. Children of non-European, immigrant mothers were most likely to be poor, and there was a higher likelihood of children from single-parent families to live in chronic poverty during the first 10 years.

Conclusion

A large proportion of children are exposed to poverty before 10 years of age. More effective public policies could reduce child poverty.

Résumé

Objectifs

La pauvreté durant l’enfance est associée aux maladies chroniques des adultes. Les objectifs de l’étude étaient d’examiner l’exposition à la pauvreté durant les 10 premières années de vie dans l’Étude Longitudinale du Développement des Enfants du Québec (ÉLDEQ) selon trois mesures de pauvreté et d’explorer les caractéristiques familiales associées.

Méthode

Les données de 1 334 participants à l’ÉLDEQ ont été recueillies annuellement à la maison de 5 mois à 10 ans. Le revenu annuel du ménage et ses sources ont été documentés à chaque entrevue. Le statut de pauvreté a été opérationnalisé ainsi: 1) sous le seuil de faible revenu de Statistiques Canada, 2) recevoir du Bien-être social, 3) faire partie du plus bas quintile de statut socioéconomique. Nous avons estimé la prévalence de la pauvreté des enfants à chaque âge. La modélisation par classes latentes de croissance a permis d’identifier des sous-groupes ayant des trajectoires de pauvreté semblables. La durée de pauvreté selon chaque mesure a été calculée pour la petite enfance, l’âge scolaire et les 10 premières années de vie.

Résultats

Quatre trajectoires de pauvreté ont été identifiées: pauvreté stable, probabilité décroissante, probabilité croissante et jamais pauvre. Les trois mesures de pauvreté ne regroupent pas les mêmes populations, cependant leurs caractéristiques sont semblables. Les enfants de mères immigrantes non-Européennes sont les plus à risque d’être exposés à la pauvreté alors qu’un plus grand nombre d’enfants de familles monoparentales a vécu chroniquement pauvre durant leurs 10 premières années.

Conclusion

Un grand nombre d’enfants est exposé à la pauvreté avant 10 ans. Des politiques plus efficaces pourraient réduire la pauvreté des enfants.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Chen E, Martin AD, Matthews KA. Trajectories of socioeconomic status across children’s lifetime predict health. Pediatrics 2007;120(2):e297–e303.

Séguin L, Nikiéma B, Gauvin L, Zunzunegui MV. Duration of poverty and child health in the Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development: Longitudinal analysis of a birth cohort. Pediatrics 2007;119(5):e1063–e70.

Spencer N. Poverty and Child Health, 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Radcliffe Medical Press, 2000.

Spencer N, Blackburn C. Prevalence and social patterning of limiting long-term illness/disability in children and young people under the age of 20 years in 2001: UK census-based cross-sectional study. Child: Care, Health & Development 2010;36(4):566–73.

UNICEF. An overview of child well-being in rich countries. Innocenti Report Card 7. Florence, Italy: UNICEF, Innocenti Research Centre, 2007.

Adler N, Stewart J. Health disparities across the lifespan: Meaning, methods and mechanisms. Ann NY Acad Sci 2010;1186(The Biology of Disadvantage): 5–23.

Braveman P, Barclay C. Health disparities beginning in childhood: A life-course perspective. Pediatrics 2009;124:S163–S175.

Braveman PA, Egerter SA, Mockenhaupt RE. Broadening the focus. The need to address the social determinants of health. Am J Prev Med 2011;40:S4–S18.

Pollitt RA, Kaufman JS, Rose KM, Diez-Roux AV, Zeng D, Heiss G. Early-life and adult socioeconomic status and inflammatory risk markers in adulthood. Eur J Epidemiol 2007;22:55–66.

Conroy K, Sandel M, Zuckerman B. Poverty grown up: How childhood socio-economic status impacts adult health. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2010;31:154–60.

Harper S, Lynch J, Davey Smith G. Social determinants and the decline of cardiovascular diseases: Understanding the links. Annu Rev Public Health 2011;32:39–69.

Pollitt RA, Rose KM, Kaufman JS. Evaluating evidence for models of life course socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2005;5:7–19.

Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Chen E, Matthews KA. Childhood socioeconomic status and adult health. Ann NY Acad Sci 2010;1186(The Biology of Disad-vantage):37–55.

Guo G, Harris KM. The mechanisms mediating the effects of poverty on children’s intellectual development. Demography 2000;37(4):431–47.

Kaplan GA, Turrell G, Lynch JW, Everson SA, Helkala EL, Salonen JT. Childhood socioeconomic position and cognitive function in adulthood. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30(2):256–63.

Richards M, Hardy R, Kuh D, Wadsworth EJ. Birthweight, postnatal growth and cognitive function in a national UK birth cohort. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:342–48.

Yeung WJ, Linver MR, Brooks-Gunn J. How money matters for young children’s development: Parental investment and family processes. Child Development 2002;73(6):1861–79.

Campaign 2000 RCoCaFPiC. Reduced poverty=Better health for all. Toronto, ON, 2010.

CCSD. The Canadian Fact Book on Poverty-2000. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Council on Social Development, 2000.

National Council of Welfare. The cost of poverty. Ottawa: National Council of Welfare, 2002.

National Council of Welfare. Poverty profile. Ottawa: National Council of Welfare, 2010.

Campaign 2000 Rc. Family security in insecure times: The case for a poverty reduction strategy in Canada. Toronto, 2008.

Dixon J, Macarov D. Poverty, A Persistent Global Reality. London and New York: Routledge, 1998.

Fréchet G, Gauvreau D, Poirier J. Statistiques sociales, pauvreté et exclusion sociale. Perspectives québécoises, canadiennes et internationales. Montréal, QC: Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2011.

Fréchet G, Lanctôt P, Morin A. Prendre la mesure de la pauvreté. Proposition d’indicateurs de pauvreté, d’inégalités et d’exclusion sociale afin de mesurer les progrès réalisés au Québec. Québec, 2009.

Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Chideya S, Marchi KS, Metzler M, et al. Socioeconomic status in health research. One size does not fit all. JAMA 2005;294(22):2879–88.

Noël A. Une lutte inégale contre la pauvreté et l’exclusion sociale. In: Fahmy M (Ed.), L’état du Québec 2011. Montréal: Boréal, 2011.

Alkire S, Foster J. Understandings and Misunderstandings of Multidimensional Poverty Measurement. Oxford: University of Oxford, 2011.

Mowafi M, Khawaja M. Poverty. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005;59:260–64.

Oakes JM, Rossi PH. The measurement of SES in health research: Current practice and steps toward a new approach. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:769–84.

Singh-Manoux A, Clarke P, Marmot M. Multiple measures of socio-economic position and psychosocial health: Proximal and distal measures. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:1192–99.

Raïq H, Bernard P, Van den Berg A. Family type and poverty under different welfare regimes: A comparison of Canadian provinces and select European countries. In: Fréchet G, Gauvreau D, Poirier J (Eds.), Statistiques sociales, pauvreté et exclusion sociale, Perspectives québécoises, canadiennes et internationales. Montréal: Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2011.

Brochu P, Makdissi P, Tahoan L. Le Québec, champion canadien de la lutte contre la pauvreté? In: Fahmy M (Ed.), L’état du Québec 2011. Montréal: Boréal, 2011.

Willms DJ, Shields M. A measure of socioeconomic status for the National Longitudinal Survey of Children. Ottawa: Atlantic Centre for Policy Research in Education, University of New Brunswick and Statistics Canada, 1996.

Jetté M, DesGroseillers L. Survey description and methodology. In: Longitudinal Study of Child Development in Quebec (QLSCD 1998-2002), vol. 1, no. 1. Research Report. Québec, QC: Institut de la statistique du Québec, 2000.

Jetté M. Survey description and methodology, Part I — Logistics and longitudinal data collections. In: Québec Longitudinal Study of Child Development (QLSCD 1998-2002) - From Birth to 29 Months, vol. 2, no. 1. Quebec: Institut de la statistique du Québec, 2002.

Jetté M, Desgroseillers L. Survey description and methodology. In: Longitudinal Study of Child Development in Quebec (QLSCD 1998-2002), Vol 1, No 1. Quebec: Institut de la statistique du Québec, 2000.

Thibault J, Jetté M, Desrosiers H, Gingras L. Concepts, definitions and operational aspects, Part I — QLSCD: Overview of the study and the survey instruments for the 1999 and 2000 rounds. In: Québec Longitudinal Study of Child Development (QLSCD 1998-2002), Vol. 2, No. 12. Québec: Institut de la sta-tistique du Québec, 2002.

Giles P. Low income measurement in Canada. Ottawa: Minister of Industry, 2004.

Statistics Canada LICO. Low income cut-offs. What are the LICOs? Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2009.

Desrosiers H, Simard M, Fontaine C. Qui est pauvre, qui ne l’est pas? Faible revenu et pauvreté subjective chez les jeunes familles. Montréal: Institut de la statistique du Québec, 2008.

Shewell H. Canada. In: Dixon J, Dixon J, Macarov D (Eds.), Poverty: A Persistent Global Reality. New York, NY: Routledge, 1998.

Statistics Canada. National occupational classification for statistics. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2006.

Gibbings JC. Calculation of SES from information collected. In: Étude Longi-tudinale du Développement des Enfants du Québec [ÉLDEQ, Québec Children’s Survey]. Unpublished manuscript. Fredericton, NB: Canadian Research Institute for Social Policy (CRISP), University of New Brunswick, 2009.

Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The social determinants of health: Coming of age. Ann Rev Public Health 2011;32:381–98.

Luo Y, Waite LJ. The impact of childhood and adult SES on physical, mental, and cognitive well-being in later life. J Gerontol 2005;60B(2):S93–S101.

Lynch J, Davey Smith G. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. Annu Rev Public Health 2005;26:1–35.

Poulton R, Caspi A, Milne B, Thomson W, Taylor A, Sears M, et al. Association between children’s experience of socioeconomic disadvantage and adult health: A life-course study. The Lancet 2002;360:1640–45.

Barayandema A, Fréchet G, Lecheaume A, Savard F. La pauvreté, les inégalités et l’exclusion sociale au Québec: vers l’horizon 2013. État de situation 2011. Montréal, 2011.

Plante C, Van den Berg A. How much poverty can’t the government be blamed for? A counterfactual decomposition of poverty rates in Canada’s largest provinces. In: Fréchet G, Gauvreau D, Poirier J (Éds.), Statistiques sociales, pauvreté et exclusion sociale. Perspectives québécoises, canadiennes et internationales. Montréal: Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2011.

American Academy of Pediatrics CoPR. Race/ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status — research exploring their effects on child health: A subject review. Pediatrics 2000;105(6):1349–51.

Chen E, Matthews KA, Boyce WT. Socioeconomic differences in children’s health: How and why do these relationships change with age? Psychological Bull 2002;128:295–329.

Malat J, Oh JH, Hamilton MA. Poverty experience, race, and child health. Public Health Rep 2005;120:442–47.

Spencer N. Maternal education, lone parenthood, material hardship, maternal smoking, and longstanding respiratory problems in childhood: Testing a hierarchical conceptual framework. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005;59:842–46.

UNICEF. The Children Left Behind: A league table of inequality in child well-being in the world’s rich countries. Florence: UNICEF, Innocenti Research Centre, 2010.

Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ. The effects of poverty on children. The Future of Children and Poverty 1997;7:55–71.

Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J. Consequences of Growing Up Poor. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1997.

Lupien SJ, King S, Meaney MJ, McEwen BS. Child’s stress hormone levels correlate with mother’s socioeconomic status and depressive state. Biol Psychiatry 2000;48(10):976–80.

Petterson SM, Albers AB. Effects of poverty and maternal depression on early child development. Child Dev 2001;72(6):1794–813.

Evans GW, Kim P. Childhood poverty and health. Cumulative risk exposure and stress dysregulation. Psychological Sci 2007;18(11):953–57.

Evans GW, Pilyoung K. Multiple risk exposure as a potential explanatory mechanism for the socioeconomic status-health gradient. Ann NY Acad Sci 2010;1186(The Biology of Disadvantage):174–89.

Korzyrskyj AL, Kendall GE, Jacoby P, Zubrick SR. Association between socio-economic status and the development of asthma: Analysis of income trajectories. Am J Public Health 2010;100(3):540–46.

Najman JM, Hayatbakhsh MR, Clavarino A, Bor W, O’Callaghan MJ, Williams GM. Family poverty over the early life course and recurrent adolescent and young adult anxiety and depression: A longitudinal study. Am J Public Health 2010;100(9):1719–23.

Phipps S. The impact of poverty on health. Ottawa: Canadian Population Health Initiative, Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2003.

Pickering T. Cardiovascular pathways: Socioeconomic status and stress effects on hypertension and cardiovascular function. Ann NY Acad Sci 1999;896(1):262–77.

Pulkki L, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L, Ravaja N, Viikari J. Child-rearing attitudes and cardiovascular risk among children: Moderating influence of parental socioeconomic status. Prev Med 2003;36:55–63.

Wells NM, Evans GW, Beavis A, Ong AD. Early childhood poverty, cumulative risk exposure, and body mass index trajectories through young adulthood. Am J Public Health 2010;100(12):2507–12.

OECD. Growing unequal?: Income distribution and poverty in OECD countries. Geneva, Switzerland: OECD, 2008.

Hansen K, Jones E, Joshi H, Budge D. Millennium Cohort Study Fourth Survey: A User’s Guide to Initial Findings, 2nd Edition. London, England: Centre for Longitudinal Studies, Institute of Education, University of London, 2010.

Michaud S. The National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth — Overview and Changes after Three Cycles. Special Issue on Longitudinal Methodology, Canadian Studies in Population 2001;28(2):391–405.

National Council of Welfare. The dollars and sense of solving poverty. Ottawa: National Council of Welfare, 2011.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Acknowledgements of support: This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Grant Number 00309MOP-123079. Data were collected by the Institut de la Statistique du Québec, Direction Santé Québec. The IRSPUM and CRCHUM received infrastructure funding from the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec. LG holds a CIHR/CRPO Applied Public Health Chair on Neighbourhoods, Lifestyle, and Healthy Body Weight. GP holds a CIHR Applied Public Health Research Chair. MTT is funded by a postdoctoral CIHR fellowship (CIHR #181755) and by a Young Investigator Award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation. These funding agencies were not involved in the study design, data analyses, data interpretation or manuscript writing and submission processes.

Conflict of Interest: None to declare.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Séguin, L., Nikiéma, B., Gauvin, L. et al. Tracking Exposure to Child Poverty During the First 10 Years of Life in a Quebec Birth Cohort. Can J Public Health 103, e270–e276 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03404234

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03404234