Abstract

It is important for economic evaluations in healthcare to cover all relevant information. However, many existing evaluations fall short of this goal, as they fail to include all the costs and effects for the relatives of a disabled or sick individual. The objective of this study was to analyse how relatives’ costs and effects could be measured, valued and incorporated into a cost-effectiveness analysis.

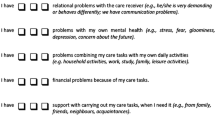

In this article, we discuss the theories underlying cost-effectiveness analyses in the healthcare arena; the general conclusion is that it is hard to find theoretical arguments for excluding relatives’ costs and effects if a societal perspective is used. We argue that the cost of informal care should be calculated according to the opportunity cost method. To capture relatives’ effects, we construct a new term, the R-QALY weight, which is defined as the effect on relatives’ QALY weight of being related to a disabled or sick individual. We examine methods for measuring, valuing and incorporating the R-QALY weights. One suggested method is to estimate R-QALYs and incorporate them together with the patient’s QALY in the analysis. However, there is no well established method as yet that can create R-QALY weights. One difficulty with measuring R-QALY weights using existing instruments is that these instruments are rarely focused on relative-related aspects. Even if generic quality-of-life instruments do cover some aspects relevant to relatives and caregivers, they may miss important aspects and potential altruistic preferences. A further development and validation of the existing caregiving instruments used for eliciting utility weights would therefore be beneficial for this area, as would further studies on the use of time trade-off or Standard Gamble methods for valuing R-QALY weights. Another potential method is to use the contingent valuation method to find a monetary value for all the relatives’ costs and effects.

Because cost-effectiveness analyses are used for decision making, and this is often achieved by comparing different cost-effectiveness ratios, we argue that it is important to find ways of incorporating all relatives’ costs and effects into the analysis. This may not be necessary for every analysis of every intervention, but for treatments where relatives’ costs and effects are substantial there may be some associated influence on the cost-effectiveness ratio.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Donaldson C, Tarrier N, Burns A. Determinants of carer stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatric Psychiatry 1998; 13: 248–56

Han B, Haley WE. Family caregiving for patients with stroke: review and analysis. Stroke 1999; 30: 1478–85

Whitlatch CJ. Distress and burden for family caregivers. In: Wimo A, Jönsson B, Karlsson G, et al., editors. Health economics of dementia. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 1998: 123–38

Murphy N, Christian B, Caplin D, et al. The health of caregivers for children with disabilities: caregiver perspectives. Child Care Health Dev 2007; 33(2): 180–7

Stolz P, Udén G, Willman A. Support for family carers who care for an elderly person at home: systematic review. Scand J Caring Sci 2004; 18: 111–9

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005

Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russel LB, et al. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996

Brouwer WB, van Exel NJA, Koopmanschap MA, et al. The valuation of informal care in economic appraisal: a consideration of individual choice and societal costs of time. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1999; 15(1): 147–60

Koopmanschap MA, Brouwer WB. Indirect costs and costing informal care. In: Wimo A, Jönsson B, Karlsson G, et al., editors. Health economics of dementia. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 1998: 245–56

Aneshensel CS, Pearlin LI, Schuler RH. Stress, role captivity, and the cessation of caregiving. J Health Soc Behav 1993; 34(1): 54–70

Brouwer WB, van Exel NJA, van den Berg B, et al. Process utility from providing informal care: the benefit of caring. Health Pol 2005; 74: 85–99

Nolan MR, Grant G, Keady J. Understanding family care: a multidimensional model of caring and coping. Buckingham: Open University Press, 1996

White CL, Lauzon S, Yaffe MJ, et al. Toward a model of quality of life for family caregivers of stroke survivors. Qual Life Res 2004; 13: 625–38

Davidson T, Krevers B, Levin L-Å. In pursuit of QALY weights for relatives: empirical estimates in relatives caring for older people. Eur J Health Econ 2008; 9: 285–92

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Updated guide to the methods of technology appraisal. London: NICE, 2008 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.nice.org.uk/media/B52/A7/TAMethodsGuideUpdated June2008.pdf [Accessed 2009 Nov 30]

Läkemedelsförmånsnämnden. General guidelines for economic evaluations from the Pharmaceutical Benefits Board. Stockholm: Pharmaceutical Benefits Board (Läkemedelsförmånsnämnden), 2003 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.tlv.se/Upload/English/ENG-lfnar-2003-2.pdf [Accessed 2009 Nov 30]

Basu A, Meltzer D. Implications of spillover effects within the family for medical cost-effectiveness analysis. J Health Econ 2005; 24: 751–73

Prosser L, Hammitt J, Keren R. Measuring health preferences for use in cost-utility and cost-benefit analyses of interventions in children: theoretical and methodological considerations. Pharmacoeconomics 2007; 25(9): 713–26

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine (review) and memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (amended). London: NICE, 2007

Bolin K, Lindgren B, Lundborg P. Your next of kin or your own career? Caring and working among the 50+ of Europe. J Health Econ 2008; 27(3): 718–38

Andrén S, Elmståhl S. Family caregivers’ subjective experiences of satisfaction in dementia care: aspects of burden, subjective health and sense of coherence. Scand J Caring Sci 2005; 19: 157–68

Johannesson M. Theory and methods of economic evaluation of health care. Stockholm: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1996

Culyer AJ. The normative economics of health care finance and provision. In: McGuire A, Fenn P, Mayhew K, editors. Providing health care: the economics of alternative systems of finance and provision. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991:65–98

Williams A. Cost-benefit analysis: applied welfare economics or general decision aid. In: Williams A, Giardina E, editors. Efficiency in the public sector. London: Edward Elgar, 1993: 65–79

Birch S, Donaldson C. Valuing the benefits and costs of health care programmes: where’s the ‘extra’ in extra-welfarism? Soc Sci Med 2003; 56: 1121–33

Canadian agency for drugs and technologies in health. Guidelines for the economic evaluation of health technologies. 3rd ed. Ottawa: CADTH, 2006 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.cadth.ca/media/pdf/1 86_EconomicGuidelines_e.pdf [Accessed 2009 Nov 30]

Torrance GW, Feeny DH. Utilities and quality adjusted life years. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1989; 5: 559–75

van den Berg B, Brouwer WB, Koopmanschap MA. Economic valuation of informal care; an overview of methods and applications. Eur J Health Econ 2004; 5: 36–45

Mulvaney-Day NE. Using willingness to pay to measure family members’ preferences in mental health. J Ment Health Pol Econ 2005; 8: 71–81

van den Berg B, Bleichrodt H, Eeckhoudt L. The economic value of informal care: a study of informal caregivers’ and patients’ willingness to pay and willingness to accept for informal care. Health Econ 2005; 14: 363–76

van den Berg B, Brouwer WB, van Exel NJA, et al. Economic valuation of informal care: the contingent valuation method applied to informal caregiving. Health Econ 2005; 14(2): 169–83

Ryan M. Using conjoint analysis to take account of patient preferences and go beyond health outcomes: an application to in vitro fertilisation. Soc Sci Med 1999; 48: 535–46

Ryan M, Hughes J. Using conjoint analysis to assess women’s preferences for miscarriage management. Health Econ 1997; 6: 261–73

van den Berg B, Al M, van Exel NJA, et al. Economic valuation of informal care: conjoint analysis applied in a heterogeneous population of informal caregivers. Value Health 2008; 11(7): 1041–50

van den Berg B, Maiwenn A, Brouwer W, et al. Economic valuation of informal care: the conjoint measurement method applied to informal caregiving. Soc Sci Med 2005; 61: 1342–55

Ferrer-i-Carbonell A, van Praag BMS. The subjective costs of health losses due to chronic diseases: an alternative model for monetary appraisal. Health Econ 2002; 11: 709–22

van den Berg B, Ferrer-i-Carbonell A. Monetary valuation of informal care: the well-being valuation method. Health Econ 2007; 16(11): 1227–44

Busschbach JJV, Brouwer WB, van der Donk A, et al. An outline for a cost-effectiveness analysis of a drug for patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacoeconomics 1998; 13(1): 21–34

Mohide EA, Torrance GW, Streiner DL, et al. Measuring the wellbeing of family caregivers using the time trade-off technique. J Clin Epidemiol 1988; 41(5): 475–82

Prosser LA, Bridges CB, Uyeki TM, et al. Values for preventing influenza-related morbidity and vaccine adverse events in children. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2005; 3: 18

McMillan SC, Mahon MM. The impact of hospice services on the quality of life of primary caregivers. Oncol Nurs Forum 1994 Aug; 21(7): 1189–95

Brouwer W, van Exel N, van Gorp B, et al. The CarerQol instrument: a new instrument to measure care-related quality of life of informal caregivers for use in economic evaluations. Qual Life Res 2006; 15: 1005–21

Johannesson M, Liljas B, O’Connor RM. Hypothetical versus real willingness to pay: some experimental results. Appl Econ Lett 1997; 4: 149–51

Karlsson G, Jönsson B, Wimo A, et al. Methodological issues in health economic studies of dementia. In: Wimo A, Jönsson B, Karlsson G, et al., editors. Health economics of dementia. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 1998: 161–70

Arrow K. A difficulty in the concept of social welfare. J Pol Econ 1950; 58(4): 328–46

Koopmanschap MA, van Exel NJA, van den Berg B, et al. An overview of methods and applications to value informal care in economic evaluations of healthcare. Pharmacoeconomics 2008; 26(4): 269–80

Brouwer WB. Too important to ignore: informal caregivers and other significant others. Pharmacoeconomics 2006; 24(1): 39–41

Brouwer WB, van Exel NJA, van den Berg B, et al. Burden of caregiving: evidence of objective burden, subjective burden, and quality of life impacts on informal caregivers of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 51(4): 570–7

Dixon S, Walker M, Salek S. Incorporating carer effects into economic evaluation. Pharmacoeconomics 2006; 24(1): 43–53

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this study was provided by grants from Apoteket AB’s research fund and from the county council of Östergötland, Sweden. The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in writing and publishing this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davidson, T., Levin, LÅ. Is the societal approach wide enough to include relatives?. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 8, 25–35 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03256163

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03256163