Abstract

Although some research has assessed both the content and mode of information processing in subclinical depressive states, studies have yet to address these issues in clinical depression. In particular, research has not examined whether there is evidence of content specificity in the processing of state and trait depressive information, and whether this information is differentially processed in automatic versus effortful processing modes. In this study, depressed inpatients were compared with normals controls on a processing task that allowed for the assessment of both state and trait information processing in automatic or effortful modes. Results indicated better recall overall for control subjects, but when recall within subject conditions was taken into account, depressed patients showed diffuse recall across both state and trait depressive information. The schemas apparent in clinical depression therefore do not appear to be specific to trait depressive information and may function to facilitate the acquisition of any depression-relevant information.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1987).Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed., rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

Bargh, J. A., & Tota, M. E. (1988). Context-dependent automatic processing in depression: Accessibility of negative constructs with regard to self but not others.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 925–939.

Beck, A. T. (1967).Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York: International University Press.

Beck, A. T. (1976).Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York: International Universities Press.

Beck, A. T. (1987). Cognitive models of depression.Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 1, 5–37.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Garbin, M. G. (1988). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation.Clinical Psychology Review, 8, 77–100.

Clark, D. A. (1986). Cognitive-affective interaction: A test of the “specificity” and the “generality” hypotheses.Cognitive Therapy and Research, 10, 607–624.

Clark, D. A., Beck, A. T., & Brown, G. (1989). Cognitive mediation in general psychiatric outpatients: A test of the content-specificity hypothesis.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 958–964.

Chaplin, W. F., John, O. P., & Goldberg, L. R. (1988). Conceptions of states and traits: Dimensional attributes with ideas as prototypes.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 541–557.

Craik, F. I. M., & Tulving, E. (1975). Depth of processing and the retention of words in episodic memory.Journal of Experimental Psychology, 104, 268–294.

Derry, P. A., & Kuiper, N. A. (1981). Schematic processing and self-reference in clinical depression.Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 90, 286–297.

Dobson, K. S., & Shaw, B. F. (1987). Specificity and stability of self-referent encoding in clinical depression.Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 96, 34–40.

Gotlib, I. H., McLachlan, A. L., & Katz, A. N. (1988). Biases in visual attention in depressed and nondepressed individuals.Cognition and Emotion, 2, 185–200.

Greenberg, M. S., & Beck, A. T. (1989). Depression versus anxiety: A test of the content specificity hypothesis.Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 98, 9–13.

Ingram, R. E. (1984). Toward an information processing analysis of depression.Cognitive Therapy and Research, 8, 443–478.

Ingram, R. E. (1990). Self-focused attention in clinical disorders: Review and a conceptual model.Psychological Bulletin, 107, 156–176.

Ingram, R. E., & Holle, C. (1992). Cognitive science of depression. In D. J. Stein & J. E. Young (Eds.),Cognitive science and clinical disorders (pp. 188–210). San Diego: Academic Press.

Ingram, R. E., Kendall, P. C., Smith, T. W., Donnell, C., & Ronan, K. (1987). Cognitive specificity in emotional distress.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 734–742.

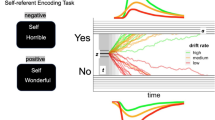

Ingram, R. E., Partridge, S., Scott, W., & Bernet, C. Z. (1994). Schema specificity in subclinical syndrome depression: Distinctions between automatically versus effortfully encoded state and trait depressive information.Cognitive Therapy and Research, 18, 195–209.

Ingram, R. E., & Reed, M. J. (1986). Information encoding in depression: Findings, issues, and future directions. In R. E. Ingram (Ed.),Information processing approaches to clinical psychology. Orlando: Academic Press.

Ingram, R. E., Smith, T. W., & Brehm, S. S. (1983). Depression and information processing: Self-schemata and the encoding of self-referent information.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 412–420.

Myers, J. F., Lynch, P. B., & Bakal, D. A. (1989). Dysthymic and hypomanic self-referent effects associated with depressive illness and recovery.Cognitive Therapy and Research, 13, 195–209.

Posner, M. I. (1978).Chronometric explorations of mind. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Segal, Z. V., & Shaw, B. F. (1986). Cognition in depression: A reappraisal of Coyne and Gotlib's critique.Cognitive Therapy and Research, 10, 671–694.

Shiffrin, R. M., & Schneider, W. (1977). Controlled and automatic human information processing: II. Perceptual learning, automatic attending and a general theory.Psychological Review, 84, 127–190.

Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., Gibbon, M., & First, M. B. (1990).Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R — Patient Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Teasdale, J. D. (1983). Negative thinking in depression: Cause, effect, or reciprocal relationship?Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy, 5, 3–25.

Teasdale, J. D. (1988). Cognitive vulnerability to persistent depression.Cognition and Emotion, 2, 247–274.

Wenzlaff, R. M., Wegner, D. M., & Roper, D. W. (1988). Depression and mental control: The resurgence of unwanted negative thoughts.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55, 882–892.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

This research was supported by grant MH44715 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ingram, R.E., Fidaleo, R.A., Friedberg, R. et al. Content and mode of information processing in major depressive disorder. Cogn Ther Res 19, 281–293 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02230401

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02230401