Abstract

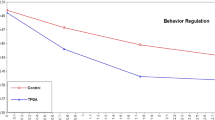

The effects of teacher-directed cognitive self-instruction (TI) were compared with an instructions-only component control condition (IO) in order to examine the former's efficacy as a primary prevention strategy. In a quasi-experimental design. two intact high school psychology classes were randomly assigned to either TI or IO. Each condition lasted for eight 45-minute class periods, and each group was given an in vivo homework assignment. Pretreatment equivalence and demand analyses yielded no evidence of differences. Results of a posttreatment measure of attitude toward treatments and a pre- and posttreatment measure of state anxiety suggested that trainerdirected cognitive self-instruction may be a promising primary prevention strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Altmaier, E. M., Ross, S. L., Leary, M. R., & Thornborough, M. (1982). Matching stress inoculations's treatment components to client's anxiety mode.Journal of Counseling Psychology, 29 331–334.

Baker, S. B., Thomas, R. N., & Munson, W. W. (1983). Effects of cognitive restructuring and structured group discussion as primary prevention strategies.School Counselor, 31 26–33.

Bandura, A. (1969).Principles of behavior modification. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Carroll, M. R. (1981). End the plague on the house of guidance—make counseling part of the curriculum.National Association of Secondary School Principals Bulletin, 65 17–22.

Cormier, W. H. & Cormier, L. S. (1979).Interviewing strategies for helpers. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Cottingham, H. F. (1973). Psychological education, the guidance function, and the school counselor.School Counselor, 20 40–45.

Cowen, E. L. (1982). Primary prevention research: Barriers, needs and opportunities.Journal of Prevention, 2(3), 131–137.

Craighead, W. E. (1982). A brief clinical history of cognitive-behavior therapy with children.School Psychology Review, 11 5–12.

Craighead, W. E., Meyers, A. W., Wilcoxon-Craighead, L., & McHale, S. M. (1983). Issues in cognitive-behavior therapy with children. In M. Rosenbaum, C. M. Franks, and Y. Jaffe (Eds.),Perspectives on behavior therapy in the eighties. New York: Springer, pp. 234–261.

Goldfried, M. R. (1980). Psychotherapy as coping skills training. In M. J. Mahoney (Ed.),Psychotherapy process: Current issues and future directions. New York: Plenum, pp. 89–120.

Goldfried, M. R. & Sobocinski, D. (1975). Effects of irrational beliefs on emotional arousal.Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43 504–510.

Gormally, J., Varvil-Weld, D., Raphael, R., & Sipps, G. (1981). Treatment of socially anxious college men using cognitive counseling and skills training.Journal of Counseling Psychology, 28 147–157.

Guerney, B. G., Guerney, L. F., & Andronico, M. P. (1966). Filial therapy.Yale Scientific Magazine, 40 6–26.

Himle, D. P., Thyer, B. A., & Papsdorf, J. D. (1982). Relationship between rational beliefs and anxiety.Cognitive Therapy and Research, 6 219–233.

Ivey, A. E. (1976). An invited response. The counselor as teacher.Personnel and Guidance Journal, 54 431–434.

Jacobs, M. K. & Cochran, S. D. (1982). The effects of cognitive restructuring on assertive behavior.Cognitive Therapy and Research, 6 63–76.

Jason, L. A. (1980). Prevention in the schools: Behavioral approaches. In R. H. Price, R. E. Ketterer, B. C. Bader, & J. Monahan (Eds.),Prevention in mental health, research, policy, and practice (Vol. 1). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, pp. 109–134.

Kazdin, A. E.Client expectancy for change. Unpublished survey. Penn State University, undated.

Meichenbaum, D. (1977).Cognitive behavior modification. New York: Plenum.

Spielberger, D. C., Gorsuch, R. L., & Lushene, R. E. (1970).State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (“Self-Evaluation Questionnaire”). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc.

Stone, G. L. (1980).A cognitive-behavioral approach to counseling psychology. New York: Praeger.

Stone, G. L. & Noce, A. (1980). Cognitive training for young children: Expanding the counselor's role.Personnel and Guidance Journal, 58 416–420.

Wise, E. H. & Haynes, S. N. (1983). Cognitive treatment of test anxiety: Rational restructuring versus attentional training.Cognitive Therapy and Research, 7 69–78.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Stanley B. Baker is Associate Professor of Education at the Division of Counseling and Educational Psychology, Pennsylvania State University. James N. Butler is Psychology Teacher, Tyrone Area High School, Tyrone, PA.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baker, S.B., Butler, J.N. Effects of preventive cognitive self-instruction training on adolescent attitudes, experiences, and state anxiety. J Primary Prevent 5, 17–26 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01332030

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01332030