Abstract

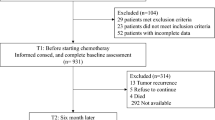

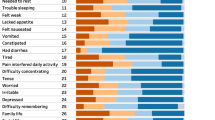

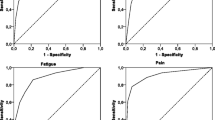

An extensive quality of life (QOL) investigation of the effects of chemotherapy in patients with generalized malignant melanoma included a validation study of involved questionnaires. The QOL domains of the three basic quality of life questionnaires, the EORTC QLQ-C36 (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Core Questionnaire), a study-specific malignant melanoma (MM) module and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale vs. the Cancer Inventory of Problem Situations (CIPS) were validated by correlation analyses. The value of using attending nurses and/or next of kin to assess the patients' situation was also examined. Functional and symptom scales of the C36 and the subscales of the HAD showed appropriate convergent and discriminant validity when compared with the CIPS. The subscales of the MM module had less clear relationships, probably due to lack of accordance in the CIPS. Assessments of attending nurses revealed very low correlations with the patients' measures. They under-estimated significantly series of specific symptoms and overestimated nausea and the overall quality of life of the patients. However, assessments of close relatives, mostly spouses, showed moderate to high correlations and no significant difference. These results further strengthen the overall validity of the modular approach of the EORTC QLQ technique. In this context of active chemotherapy in patients with advanced cancer disease, relatives seem to be better surrogates than the attending nurses in assessing the patients' quality of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Aaronson NK, Bakker W, Stewart AL, et al. Multidimensional approach to the measurement of quality of life in lung cancer clinical trials. In: Aaronson NK, Beckmann JH, eds. The Quality of Life of Cancer Patients. New York: Raven Press, 1987; 62–82.

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bullinger M, et al. The EORTC Core Quality of Life Questionnaire: Interim results of an international field study. In: Osoba D, ed. Effect of Cancer on Quality of Life. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press Inc, 1991: 185–203.

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Berman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993; 85: 365–376.

Sigurdardóttir V, Bolund C, Brandberg Y, et al. The impact of generalized malignant melanoma on quality of life evaluated by the EORTC questionnaire technique. Qual Life Res 1993; 2: 193–203.

Sigurdardótti V, Bolund C, Sullivan M. Quality of life evaluation by the EORTC questionnaire technique in patients with generalized malignant melanoma on chemotherapy. Acta Oncol 1996; 35: 149–158.

Sprangers AMG, Cull A, Bjordal K, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer approach to quality of life assessment: guidelines for developing questionnaire modules. Qual Life Res 1993; 2: 287–295.

Cella DF, Tulsky DS. Measuring quality of life today: methodological aspects. Oncology 1990; 4: 29–38.

Tulsky DS. An introduction to test theory. Oncology 1990; 4: 43–48.

Niezgoda HE, Pater JL. A validation study of the domains of the core EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire. Qual Life Res 1993; 2: 319–325.

Gough IR, Dalgleish LI. What value is given to quality of life assessment by health professionals considering response to palliative chemotherapy for advanced cancer? Cancer 1991; 68: 220–225.

Slevin ML, Plant H, Lynch D, et al. Who should measure quality of life, the doctor or the patients? Br J Cancer 1988; 57: 109–112.

Holmes S, Edburn E. Patients' and nurses' perceptions of symptom distress in cancer. J Adv Nurs 1989; 14: 840–846.

von Essen L, Sjödén P-O. Patient and staff perceptions of caring: Review and replication. J Adv Nurs 1991; 16: 1363–1374.

Aaronson NK. Methodological issues in assessing the quality of life of cancer patients. Cancer 1991; 67(3 Suppl): 844–850.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 67: 361–370.

Brandberg Y, Bolund C, Sigurdardóttir V, et al. Anxiety and depression symptoms at different stages of malignant melanoma. Psycho-Oncology 1992; 1: 71–78.

Schag CC, Heinrich RL, Ganz PA. Cancer Inventory of Problem Situations: an instrument for assessing cancer patients' rehabilitation needs. J Psychosoc Oncol 1983; 1: 11–24.

Ganz PA, Rofessrt J, Polinsky ML, et al. A comprehensive approach to the assessment of cancer patients' rehabilitation needs: The Cancer Inventory of Problem Situations and a comparison interview. J Psychosoc Oncol 1986; B(4): 27–42.

Schag CAC, Heinrich RL, Aadland RL, et al. Assessing problems of cancer patients: psychometric properties of the Cancer Inventory of Problem Situations. Health Psychol 1990; 9: 83–102.

Bergman B, Sullivan M, Sörenson S. Quality of life during chemotherapy for small cell lung cancer. II. A longitudinal study of the EORTC Core Quality of Life Questionnaire and comparison with the Sickness Impact Profile. Acta Oncol 1992; 31: 19–28.

Moorey S, Greer S, Watson M, et al. The factor structure and factor stability of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale in patients with cancer. Br J Psychiatry 1991; 158: 255–259.

Razavi D, Delvaux N, Farvacques C, et al. The screening of adjustment disorders and major depressive disorders in cancer in-patients. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 156: 79–83.

Lundqvist C, Siösteen A, Blomstrand C, et al. Spinal cord injuries. Clinical, functional and emotional status. Spine 1991; 16: 78–83.

Bergman B, Sullivan M, Sörenson S. Quality of life during chemotherapy for small cell lung cancer. I. An evaluation with generic health measures. Acta Oncol Scand 1991; 30: 947–959.

Glimelius B, Birgegård G, Hoffman K, et al. A comprehensive cancer care project to improve the overall situation of patients receiving intensive chemotherapy. J Psychosoc Oncol 1993; 11: 17–40.

Glimelius B, Birgegård G, Hoffman K, et al. Improved care of patients with small cell lung cancer. Acta Oncol Scand 1992; 31: 823–832.

Bradley JW. Distribution-free statistical tests. London: Prentice-Hall, 1968: 68–86.

Sigurdardóttir V, Bolund C, Nilson B. Quality of life: opinions about chemotherapy among patients with advanced melanoma, next of kin and care-providers. Psycho-Oncol 1995; 4: 287–300.

Holland J. Skin cancer and melanoma. In: Holland JC, Rowland JH, eds. Handbook of Psychooncology. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989; 246–249.

Brandberg Y, Bolund C, Månson-Brahme E, Ringborg U, Sjödén P-O. Psychological effects of participation in a prevention programme for individuals with increased risk for malignant melanoma. Eur J Cancer 1992; 28: 1334–1338.

Brandberg Y, Bolund C, Michelson H, Månson-Brahme E, Ringborg U, Sjödén P-O. Psychological reactions in public melanoma screening. Eur J Cancer 1992; 6: 860–863.

Brandberg Y, Månson-Brahme E, Ringborg U, Sjödén P-O. Psychological reactions in patients with malignant melanoma. Eur J Cancer 1995; 31A: 157–162.

Tibblin G, Bengtsson C, Furunes B, Lapidus L. Symptoms by age and sex. The population studies of men and women in Gothenburg, Sweden. Scand J Prim Health Care 1990; 8: 9–17.

Bodenhamer E, Achterberg-Lawlis J, Kevorkian G, Belanus A, Cofer J. Staff and patients perceptions of the psychosocial concerns of spinal cord injured persons. Am J Phys Med 1983; 62: 182–193.

Clipp EC, George LK. Patients with cancer and their spouse caregivers. Perceptions of the illness experience. Cancer 1992; 69: 1074–1079.

Clarridge BR, Massalgi MP. The use of female spouse proxies in common symptom reporting. Med Care 1989; 27: 352–365.

O'Brien J, Francis A. The use of next-of-kin to estimate pain in cancer patients. Pain 1988; 35: 171–178.

Epstein AM, Hall JA, Tognetti J, et al. Using proxies to evaluate quality of life. Can they provide valid information about patients' health status and satisfaction with medical care? Med Care 1989; 27: S91-S98.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

This study was made possible by grants from the King Gustav V Jubilee Fund, Stockholm, the Medical Faculty, University of Göteborg, Göteborg, Sweden and the Icelandic Cancer Society, Reykjavík, Iceland.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sigurdardóttir, V., Brandberg, Y. & Sullivan, M. Criterion-based validation of the EORTC QLQ-C36 in advanced melanoma: The CIPS questionnaire and proxy raters. Qual Life Res 5, 375–386 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00433922

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00433922