Abstract

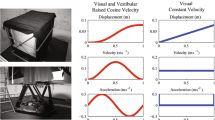

Previous studies have generally considered heading perception to be a visual task. However, since judgments of heading direction are required only during self-motion, there are several other relevant senses which could provide supplementary and, in some cases, necessary information to make accurate and precise judgments of the direction of self-motion. We assessed the contributions of several of these senses using tasks chosen to reflect the reference system used by each sensory modality. Head-pointing and rod-pointing tasks were performed in which subjects aligned either the head or an unseen pointer with the direction of motion during whole body linear motion. Passive visual and vestibular stimulation was generated by accelerating subjects at sub- or supravestibular thresholds down a linear track. The motor-kinesthetic system was stimulated by having subjects actively walk along the track. A helmet-mounted optical system, fixed either on the cart used to provide passive visual or vestibular information or on the walker used in the active walking conditions, provided a stereoscopic display of an optical flow field. Subjects could be positioned at any orientation relative to the heading, and heading judgments were obtained using unimodal visual, vestibular, or walking cues, or combined visual-vestibular and visual-walking cues. Vision alone resulted in reasonably precise and accurate head-pointing judgments (0.3° constant errors, 2.9° variable errors), but not rod-pointing judgments (3.5° constant errors, 5.9° variable errors). Concordant visual-walking stimulation slightly decreased the variable errors and reduced constant pointing errors to close to zero, while head-pointing errors were unaffected. Concordant visual-vestibular stimulation did not facilitate either response. Stimulation of the vestibular system in the absence of vision produced imprecise rod-pointing responses, while variable and constant pointing errors in the active walking condition were comparable to those obtained in the visual condition. During active self-motion, subjects made large headpointing undershoots when visual information was not available. These results suggest that while vision provides sufficient information to identify the heading direction, it cannot, in isolation, be used to guide the motor response required to point toward or move in the direction of self-motion.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ahumada AJ (1983) Bias and discriminability in aimpoint estimation. National Aeronautics and Space Administration Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, Calif

Benson AJ, Spencer MB, Stott JRR (1986) Thresholds for the detection of the direction of whole-body, linear movement in the horizontal plane. Aviat Space Environ Med 57:1088–1096

Bruss AR, Horn BKP (1983) Passive navigation. Comput Vision Graphics Image Process 21:3–20

Cutting JE (1986) Perception with an eye for motion. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass

Cutting JE, Springer K, Braren PA, Johnson SH (1992) Wayfinding on foot from information in retinal, not optical, flow. J Exp Psychol Gen 121:41–72

Diener HC, Dichgans J, Guschlbauer B, Bacher M (1986) Role of visual and static vestibular influences on dynamic posture control. Hum Neurobiol 5:105–113

Gibson JJ (1950) Perception of the visual world. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, Mass

Fox CR, Paige GD (1991) Effect of head orientation on human postural stability following unilateral vestibular ablation. J Vestib Res 1:153–160

Guedry FE (1974) Psychophysics of vestibular sensation. In: Kornhuber HH (ed) Handbook of sensory physiology, vol VI/2, part 2. Vestibular system: psychophysics, applied aspects and general interpretations. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York, pp 1–154

Gundry AJ (1978) Thresholds of perception for periodic linear motion. Aviat Space Environ Med 49:679–686

Holst E von (1954) Relations between the central nervous system and the peripheral organs. Anim Behav 2:89–94

Johnston IR, White GR, Cumming RW (1973) The role of optical expansion patterns in locomotor control. Am J Psychol 86:311–324

Koenderink JJ, van Doorn AJ (1981) Exterospecific component for the detection of structure and motion in three dimensions. J Opt Soc Am 71:953–957

Llewellyn KR (1971) Visual guidance of locomotion. J Exp Psychol 91:245–261

Longuet-Higgins HC, Prazdny K (1980) The interpretation of a moving retinal image. Proc R Soc Lond [B] 208:385–397

Paige GD, Tomko DL (1991) Eye movement responses to linear head motion in the squirrel monkey. II. Visual-vestibular interactions and kinematic considerations. J Neurophysiol 65:1183–1196

Regan D, Beverley KI (1982) How do we avoid confounding the direction we are looking and the direction we are moving? Science 215:194–196

Rieger JH, Lawton DT (1985) Processing differential image motion. J Opt Soc Am [A] 2:354–360

Richards W (1975) Visual space perception. In: Carterette EC, Friedman MP (eds) Handbook of perception, vol 5. Academic Press, New York, pp 351–386

Skavenski AA (1972) Inflow as a source of extra retinal eye position information. Vision Res 12:221–229

Sperry RW (1950) Neural basis of the spontaneous optokinetic response produced by visual inversion. J Comp Physiol Psychol 43:482–489

Walsh EG (1961) Role of the vestibular apparatus in the perception of motion on a parallel swing. J Physiol (Lond) 155:506–513

Walsh EG (1964) The perception of rhythmically repeated linear motion in the vertical plane. Q J Exp Physiol 49:58–65

Warren R (1976) The perception of egomotion. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 2:448–456

Warren WH, Morris MW, Kalish M (1988) Perception of translational heading from optical flow. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept perform 14:646–660

Warren WH, Blackwell AW, Morris MW (1989) Age differences in perceiving the direction of self-motion from optical flow. J Gerontol 44:147–153

Westheimer G, Hauske G (1975) Temporal and spatial interference with vernier acuity. Vision Res 15:1137–1141

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Telford, L., Howard, I.P. & Ohmi, M. Heading judgments during active and passive self-motion. Exp Brain Res 104, 502–510 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00231984

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00231984