Abstract

The development of applications for children, and particularly for those diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), is a challenging task. In this context, careful consideration of the characteristics of these users, along with those of different stakeholders, such as parents and teachers, is essential. Also, it is important to provide different ways of using applications through multimodal interaction, in order to adapt, as much as possible, to the users’ needs, capabilities and preferences. Providing multimodality does not mean that users will interact multimodally, but provides freedom of choice to the user. Additionally, enabling multiple forms of interaction might also help understanding what actually works better, for an audience that is not always able to express an opinion regarding what might work. In this article, we take on previous work regarding the definition of a Persona for a child diagnosed with ASD and, considering the goals above, propose and evaluate a first prototype of an application targeting the audience represented by this Persona. This application, aims to serve as a place for communication and information exchange among the child, her family, and teachers and supports multimodal interaction.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Children with special needs pose several challenges to our effort of providing ICT applications that might favor their daily life, particularly in augmenting/improving their communication with family, teachers and friends, and making new skills and knowledge acquisition simpler and more efficient.

In this regard, the authors consider that two crucial aspects can help tackle these challenges: (1) a strong understanding of the target children, their characteristics, needs and motivations; and (2) enough versatility, simplicity and naturalness on how they can interact with the proposed applications – a vital aspect, particularly for young children, for whom learning complex interactions can be harder than for adults – or even contributing to evolve their skills in specific aspects, e.g., eye contact in social contexts. Enabling natural interaction requires the exploration of multimodality and modalities characterized by a high degree of naturalness such as using voice commands or selecting something by looking at it. In this context, and despite its potential for many applications, the use of gaze interaction is yet far from everyday use and we need to learn how people actually take advantage of it – as an isolated modality or mixed, e.g., with speech [24] – and in what circumstances.

In our efforts to explore novel interaction modalities, we argue in favor of considering real scenarios (e.g., developing a speech modality alongside a medication assistant [23]), instead of “toy applications”. This has the advantage of providing a realistic context for eliciting requirements and evaluation. For the current work, our setting is provided by the ongoing project “IRIS – Towards Natural Interaction and Communication” [8], addressing a domestic scenario including a child diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD). One of our goals, in this context, is to propose an Assistant to help the child in her communication with others and leverage it to bring her everyday events, e.g., at school, to the knowledge of family and teachers, enabling them to participate and provide feedback.

After a first work regarding the definition of a Persona for a child with ASD [11], the work presented in this article is our first step on the design and development of an application that aims to accomplish the goals described above: to propose an application targeting autistic children, helping them to improve their communication with others and adopting multimodality as a base feature.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 presents background information on autism spectrum disorders and some of the efforts to develop tools to aid communication in this context. It also provides some background on the development of multimodal interaction applications. Section 3 describes the main aspects concerning the definition of the application requirements, based in a context scenario built around Personas. Section 4 shows the proposed application, highlighting its main features. After, Sect. 5, deals with the outcomes of the evaluation carried out to assess user performance, detect problems and collect suggestions. Finally, Sect. 6 presents some conclusions and routes for future developments.

2 Context and Related Work

The work presented in this article concerns a novel interactive application targeting children diagnosed with ASD. In this context, it is important to have some background on ASD, current efforts to develop technologies to address this audience, and how to design and develop multimodal interaction.

2.1 Autism Spectrum Disorders

Autism spectrum disorders are a set of neurological disorders characterized by difficulties with social interactions, verbal and nonverbal communication problems, and repetitive behaviors that are detected during the early years of childhood. The significant communication and interaction differences distinguish ASDs from other types of disorders. These disorders can be split in three different groups [25]: Autism, Asperger’s Syndrome and Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified, usually abbreviated PDD-NOS. Autism is the most serious case and a large number of affected patients do not have any kind of verbal expression, have severe motor disabilities and show some indiscipline. Asperger’s syndrome patients, referred to as “a mild form of autism” have normal or above average cognitive skills, and may also express certain atypical interests. PDD-NOS is the diagnosis that covers cases that do not fit in the other two types of disorder [4].

There is a large number of applications on the market supporting augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) features, important in the context of ASD [15]. This type of applications is essential for children unable to communicate and the Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) is the most widely used AAC system [19], enabling communication with the help of cards with different images, each one with its own meaning. However, the most common problems of this type of system are its lack of portability and organization when the child owns a high number of cards [19]. These aspects may be addressed by applications for mobile devices, enabling ways of implementing new alternatives for assisted communication, entailing a much lower cost than some types of devices and AAC systems [16]. “[...] Such devices are readily available, relatively inexpensive, and appear to be intuitive to operate. These devices also seem to be socially accepted and thus perhaps less stigmatizing when used as assistive technological aids (e.g., as SGDs) by individuals with developmental disabilities.” – Kagohara et al. [10].

Among the different applications proposed, some recent representative examples addressing communication and the development of social competences for children with ASD can be highlighted. Proloquo2go™ [2, 20] is an AAC system developed by AssistiveWare, for iOS devices, meant for people with difficulties in verbal communication. Awarded with several prizes in the categories of applications for people with special needs, this is one of the most complete programs to aid in their communication. The application uses a package of symbols called SymbolStixs Footnote 1, but it is also possible to create new symbols by using the device’s camera. As defined by PECS, each symbol is represented by one picture which can be displayed in a list or a grid. The Acapela Footnote 2 synthesized voice system is used to reproduce letters and the sentences built by the user.

ABCD SW Footnote 3 was proposed by Buzzi et al. [3] in order to “facilitate the execution of applied behavioral analysis with low-functioning autistic children”. The tutor can select the test to be carried out and its difficulty, and access the data of automatically recorded sessions. DrupalFootnote 4, a content management system, was used as the basis for this application, enabling internationalization and scalability. The system can work on different devices simultaneously, providing the tutor with a real time summary of the actions taken by the child and interactive access to the interface. The communication between the two devices is done by placing the relevant data in a database, accessible by both devices. Since it runs on the web-browser it can be used in various platforms.

iCAN, a PECS application for Android tablets, created by Chien et al. [5], aims at increasing children’s motivation to learn while stimulating their senses and communication skills. The application was designed to go beyond the traditional method of using images on physical cards, enabling the creation and editing of new digital cards to communicate. To create or edit cards, the user can draw or select an image, and record the pronunciation of the respective word. The application will read aloud the composed sentence and allows reusing it later, thus enabling the child to reuse familiar sentences. The application was tested by children aged between 5 and 16 years, with the help of tutors who had previously used PECS. Educators have provided a positive opinion on how it improved the children’s learning ability and their will to learn. Even though different from child to child, they report that the child’s evolution and cognitive growth was always visible.

CaptureMyEmotion [9] uses data received from sensors to allow the autistic child to learn and know the emotion (happy, sad, angry, ...) they are currently having. The application allows autistic children to take pictures, record video and/or sound and describe how they feel. When taking a picture, an additional image is also captured using the device’s front camera to register the child’s face, at that moment. In the end, the child can choose from a list of emotions.

Proyect@Emociones Footnote 5, by Muñoz et al. [13], aims at increasing the child’s social skills and confidence. The authors state that children with special needs increasingly use tablets and smartphones, but these devices lack solutions for the training of empathy, an issue they aim to address. Supported by a tutor, children are exposed to different problems and situations. When the answer selected by the child is correct, she is presented with an audiovisual signal used to stimulate her confidence. During evaluation, by teachers and therapists, at a school for autistic children, they concluded that children with lower levels of autism benefited more from using the application as they appear to have less issues understanding emotions and feelings than children with more difficulties.

Overall, we can say that, although there are several applications and methods for teaching and supporting autistic children, few extend beyond a basic interaction design. Moreover, although children often require observation and monitoring during the use of devices, in some cases they demonstrate willingness to use them alone. The level of autism varies from child to child, and not all cases require constant monitoring, and the use of certain learning methods that could be explored more independently might be beneficial to the child’s education.

From the applications analyzed (for which the ones mentioned above are notable examples), we observed a short supply of applications that provide multiple methods of interaction. It is reasonable to expect that, in certain cases, the existence of a multimodal solution, capable of integrating multiple devices for different types of users, as well as the possibility to use different types of modalities for interaction, and supporting multiple languages, might be beneficial to train and stimulate the capacities of children diagnosed with ASD. However, much is yet to understand about how these features would be received and which ones might be more beneficial. Additionally, and to the best of our knowledge, no such effort is reported in the literature. The work presented here aims at being the first stage of a research path addressing these aspects.

2.2 Multimodal Interaction

The interaction with a multimodal system can typically be performed resorting to speech, writing, touch, body movements, gaze and lip movements. These systems are potentially more robust than unimodal systems, since they are able to interpret multiple methods of interaction and, therefore, may resort to redundancy or complementarity to obtain the most correct interaction input possible, in different contexts. For example, uttering a voice command in a noisy environment, when supplemented with other input methods such as lip movement analysis, can dramatically increase the confidence for the recognized speech command [7, 14].

Developing Multimodal Interaction Applications

The development of multimodal interaction applications is not without its challenges. The inclusion of different interaction modalities and managing the interaction requires a proper infrastructure. Additionally, approaches that are very application specific fail to encompass the needed versatility for evolution and testing of novel interaction features.

The authors have been contributing to tackle these issues by proposing a decoupled architecture for multimodal applications, aligned with the W3C standard, along with a framework that implements it [21, 22].

For the current context of developing an application for children diagnosed with ASD, adopting this multimodal framework has, at least, two main advantages: (1) its versatility, and the off-the-shelf availability of generic modalities (such as speech interaction), for any application that adopts it; (2) its decoupled nature, providing easy addition of new components, such as novel interaction modalities, in the future. This versatility is essential to adapt the application to the outcomes of each prototype evaluation and to novel technologies deemed relevant for the application context, thus supporting a long term research effort.

3 Methods

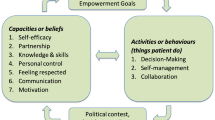

Based on our overall goals, we adopted a Persona [6] for a child diagnosed with ASD and another for a special education teacher. Based in these, we settled on a usage scenario and, from there, defined a set of initial requirements for the application.

3.1 Personas

For this work, we adopted the Persona of a child with autism, Nuno, previously proposed by us in [11]. Table 1 presents a simplified description of Nuno’s Persona, mostly omitting some details, of the original Persona, not directly relevant for the current context.

Following on our purpose of including additional Personas that can help develop for children with ASD, by considering the motivations and roles of additional stakeholders (among family and educators), we also used the Persona of a Special Education teacher, named Isabel, that will use the application with Nuno. A description of this Persona is presented in Table 2.

Other stakeholders are also being considered, in our work (mother, father, sister, speech therapist, etc.), but, at this stage, and for the sake of simplicity, we deem it enough to report just the two Personas previously mentioned.

3.2 Scenario

Our long term work aims to explore the possibilities of a child using a tablet device as a tool for school learning and to develop his communications skills. In this application scenario, used as a basis for the work presented here, we explore how the child can use the application and how a teacher can take a part in its use. The usage scenario adopted follows:

-

Scene 1: Take a picture

Nuno just finished his activity in the speech therapy session and wants to take a picture of his work to save and share the moment. When he uses the tablet, the main menu is composed of four options: “Take a picture”, “Gallery”, “Quiz” and “View my Diary”.

Touching the “Take a picture” option, the tablet displays the current view obtained from the tablet’s camera, and after pointing it to the top of the table to capture his work, he presses the button to capture the photo, which is stored on the device.

-

Scene 2: Comment picture taken

Next, the application displays the edit menu so that Nuno can choose an option: attach an emotion to the photo; add a comment to the photo; or share it in his diary so that Nuno’s family and friends can be aware of what he is doing at school. Choosing the first option, six different emotions are presented and Nuno picks the one associated with laughing. Going back, he wants to add a small text explaining what he was doing and, after that, he chooses to share it in his diary.

-

Scene 3: Quiz

Nuno then goes to the Structured Teaching classroom for a new activity. He has great difficulty establishing eye contact with others, and the tablet is used as a teaching method and to train his dialogue capabilities and communication. In this situation, both Nuno and Isabel, the teacher, use different tablets. He accesses the “Quiz” item, available from the main menu, while, at the same time, Isabel setups her tablet and a group of questions to send to Nuno’s tablet. The questions are then presented to Nuno and read aloud by a cartoon character shown in his tablet. Nuno is then encouraged to select one of the answers with the help of the teacher. While Nuno is thinking, Isabel may also control the character to make it talk, helping Nuno with the question or even to stimulate his communication.

-

Scene 4: Mother’s comment

After finishing the lesson, he decides to check on his diary. The photo he previously shared already has a comment from his mother congratulating him on his work, and he quickly replies to it expressing thanks.

3.3 Requirements

To make the envisaged scenario possible, an application for children with some level of autism needs to be developed for some mobile platform(s), allowing the use by one or more users simultaneously, in two independent devices, and adapted to different contexts, such as school and home.

Considering the Personas, context and scenario, the following requirements were derived, for the application:

-

Taking photos;

-

Saving the photos taken;

-

Deleting the photos;

-

Viewing and editing photos, including associating each of them with an emotion or a comment;

-

Connecting to another device, for simultaneous use of some features;

-

Receiving information (questions and emotions) from other device;

-

Easy and limited access to Nuno’s social network;

-

Sharing photos in Nuno’s social network;

-

Logging information by others, such as teachers or parents, to allow information interchange between them.

Additionally, we also want to enable multimodal interaction to explore how it might work in favor of increased adaptation and acceptability.

3.4 Design and Development Team

The multidisciplinary team involved in all aspects regarding the design and development of the application included, from the start: a speech therapist, with experience working with children with ASD and resorted to feedback from several regular and special education teachers with relevant experience for the subject; software developers; multimodal interaction specialists; and a speech scientist.

The process of Personas creation and the proposal of the first application mock ups was lead by the speech therapist, with inputs from the remaining team members. In this context, working with the Personas and scenario provided a common language for discussion among the team members.

4 “Tell Your Day” Application

Considering the objectives and requirements, the application was built with four main functions: (1) a camera to take photos; (2) a gallery to view and edit photos or images; (3) a quiz game to be played with a tutor; and (4) a “diary”, a minimalist way to access to a social network. All the functions were designed aiming to have some impact in the teaching and the development of capabilities for children such as Nuno.

Although the adopted multimodal framework [1] supports different languages for speech recognition and text synthesis, out-of-the-box, we focused only on the Portuguese language as the first evaluation would be made by Portuguese participants.

When running the application for the first time, a configuration panel is shown and the child’s tutor should configure the application, writing the child’s name, selecting whether he may access a social network or not, and what is the login type the child must successfully execute to access the application. A password may also be set to prevent unauthorized access to this panel, in the future.

Before describing each section of the application, we call the reader’s attention to the character that is displayed on the left side of the interface, present throughout the application (e.g., see Fig. 1). Instead of using simple output dialogue messages, this cartoon represents a small kid that is more visually appealing. It is used in an attempt to train the child communication skills by expressing emotions and using the voice synthesis modality to generate the sound of the messages also displayed in a speech balloon. As shown later, in this section, there is also the possibility of the tutor to take control of this character using a remote device (using the multi-device framework capabilities) in order to create a conversation between the character and the child.

4.1 Login

The login feature is not actually used as a method of authentication, but as a method to train the child’s interactions by using touch, speech, gaze, or even using a keyboard to write.

Two different login modes, displayed in Fig. 1, allow the interaction using two modalities each. In the first mode, the character asks what is the child’s name. Then, the name can be typed using a keyboard or spoken. If spoken, speech signal will be processed by a speech recognizer.

In the second, a set of four fruits is randomly displayed and the child must correctly select the fruit that is mentioned by the character. In this mode, selecting the correct answer can be achieved in two ways: using touch in a tablet (or a mouse), or by looking at the correct fruit (making use of eye tracking).

4.2 Main Menu

Figure 2 displays the application main menu interface, providing access to the different application functionalities.

Along with a text describing the action, each button also includes a pictogram image, helping users who may have difficulty reading. Pictograms are one of the most used methods for communication, by persons diagnosed with ASD, and are vastly used by other applications that target this same user group.

This section of the application also presents the companion character, on the left side, which can be controlled by the tutor, if desired, to interact with the child.

4.3 Camera and Gallery

While using the application, either at school or at home, the camera is a very appealing feature that provides children with the possibility of taking photos of something they saw or of their school work. All the captured photos can be viewed later, in a gallery.

Figure 3a shows the application’s interface while displaying the scene captured by the device’s back camera. Pressing the shoot button, on the bottom of the screen, the current preview is captured and stored in the device.

Different screen shots depicting photo related features: (a) the camera allows the child to take photos; (b) the edit menu, presented after taking a photo, or selecting one in the gallery; (c) the child can select a character representing an emotion; and (d) the child can freely write about the photo.

The application then displays the photo taken and an edit menu, as shown in Fig. 3b. This menu can be also accessed by selecting an image, while browsing the gallery, and each button contains a pictogram that describes its own action: (1) pick an emotion; (2) edit the photo comment; (3) share the photo in the diary; or (4) delete the photo.

4.4 Emotion Picker

The emotion picker (Fig. 3c) allows the child to attach a sentiment to the current selected photo. As studies have shown, many children with ASD have difficulties in expressing their feelings during social interaction. The same character is used here to represent six different states of mind that can be selected and the one selected is shown next to the photo in the gallery, reminding the user how he felt when he took the photo. With this first approach, we are not stating that this is the best or a complete approach to help dealing with emotions, but the inclusion of this feature may be useful for developing this topic and will be further explored in future versions of the application.

4.5 Photo Commentary

All the images or photos shown in the gallery can be associated with a comment (Fig. 3d), a simple method that can be used to motivate the child to develop her writing skills. The text written may also be used in order to describe the photo, so that later the child remembers what she did, at that moment. Furthermore, photos can be shared, along with any comment, directly in the diary, and the child’s family and friends can follow what the child is doing.

4.6 Quiz

Based on the fact that Nuno likes playing games, the goal of this feature is not only providing an additional support for teaching, but also to foster the development of the child’s communication skills. Studies have shown that many children have difficulties in making eye contact with other persons, and the immersion with computer and tablet devices may be used as a tool for dealing with that issue.

The quiz takes advantage of the multi-device capabilities and requires the use of two devices simultaneously, one for the child, where the quiz is presented, and the other for the teacher, controlling the quiz. The teacher’s device can control the quiz by sending questions, or speaking with the child using the animated character. The left part of Fig. 4 displays the application’s screen while a question is being presented. The character asks the question and then the four answers are displayed. An answer can be selected either by touching a button or using speech and uttering the selected answer. The teacher can use the animated character to speak to speak with the child, to provide tips.

4.7 Diary

Allowing Nuno to publish something on a shared space lets parents and family keep track of his actions while he is at school. To enable the interaction with a well known system, possibly used by the child’s friends, Facebook was considered as the shared space. However, considering the child’s safety and the risks of children while using an online social network, a minimalist interface was considered, working as a proxy, which only allows a small set of actions related to the child profile, such as posting or replying with a comment. Nevertheless, the parents must keep control over how the social network is used by accessing the website and only allowing a restricted group of known friends and family to see or reply to the child’s comments.

The diary, as shown in Fig. 4, on the right, follows the a similar paradigm as the one used in Facebook, showing a list of posts.

5 Evaluation

At this stage, having deployed the first prototype of the application, we were interested in getting a first evaluation of our application, mostly to detect major issues, assess if we are progressing in the good direction, and obtain feedback regarding additions considered relevant.

Since this is just the first prototype, we considered that children with ASD should not be involved in the evaluation. Preparing an evaluation with those children, as participants, requires, in our opinion, that the application has already passed through a first evaluation, to detect major issues. This should allow that any difficulties detected during an evaluation with autistic children are not due to basic usability faults, but related with their particular characteristics. This kind of procedure, we argue, is particularly relevant for target users that, for example, lack some technical skills or are less communicative to provide feedback.

In order to get a broad set of evaluation data, from different types of users, but also to inquire if the application is or might be relevant for a real use scenario, the participants chosen for this evaluation were 1 child, 2 special education teachers, and 2 regular adult users.

Participants’ performance was assessed based on their ability to execute the set of tasks presented in Table 3. For each task, several data was recorded, namely if the task was accomplished, the time needed, the total number of errors and unforeseen events, if any occurred.

All the tests were conducted on a calm environment, and all participants used the same Microsoft Surface Pro device. A desktop device, managed by an evaluator, was also used in the multi-device tasks. This evaluator impersonated the teacher Persona, while the participants took the role of the ASD child. Participants received a small explanation on how the application worked, as this was the first time they were using it.

After finishing the evaluation, all participants answered: (1) a Post-Study System Usability Questionnaire (PSSUQ), an instrument used to evaluate the user’s satisfaction with the system usability, composed by 19 questions; and (2) an ICF-US test [12] used to obtain an overall usability evaluation.

The PSSUQ items are rated using a 7-level Likert-type scale, from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree). Therefore, the lower the score the better the participant’s overall satisfaction when using the application. For reference, the full PSSUQ questionnaire is presented in Table 4. The 19 items can be subdivided into subgroups to rate specific values such as system usefulness (1 to 8), quality of information (9 to 15) and interface quality (16 to 18). Scale items number 9, 10 and 14 were classified as not applicable and were omitted, since the prototype version used in the evaluation did not have any implementation for error message’s feedback, or because the item never occurred during any of the evaluations. According to the participants’ main language, a validated Portuguese version of PSSUQ [18] was used. Nevertheless, for the sake of legibility, we report to the English version while summarizing the results.

For each of the 10 statements of the ICF-US I test [17], presented in Table 5, the user must rate whether it is considered a barrier or a facilitator while using the application. The rate can take values from \(-3\), when the item is considered a complete barrier, to 3, a complete facilitator. A final score can be computed by summing the scores from all the items. A value above 10 points means that the system has a good usability.

Also, the special education teachers answered an additional questionnaire in order to assess their views regarding: (1) the usefulness of using an improved version of the application in the educational process of children with ASD; and (2) which points or functionalities could be added, changed or removed for a future prototype version.

5.1 Performance Results

Regarding the participant’s ability to successfully complete the tasks, the results are presented in Table 6. Only one of the participants had some difficulties performing tasks 3, 4 and 5 and required help, but during the evaluation he stated he had low experience in using tablet devices. The child was the quickest participant, demonstrated joy when using the quiz game and, after finishing the evaluation, promptly asked to answer more questions.

While performing the tasks, some unforeseen events occurred that caused difficulties to the participants, but few of them required help to solve the problem. All participants had difficulties using speech to answer to the quiz, when they answered quickly, since the answer was not properly recognized. Therefore, as seen in the Table 6, task number 6 took longer than the others to finish since participants had to wait a moment before answering, giving time for the speech recognition engine to reload its configuration (grammar) for the new question.

Apart from the technical problems, some users found difficulties when navigating back and forward between the application sections and recognizing the meaning of the pictograms in the buttons which, in some cases, had no caption associated.

PSSUQ results

Figure 5 presents the average score values, per item, obtained using the PSSUQ.

Analyzing the results and considering the scale used in the PSSUQ, the questions with the best ratings (smaller is better) were “8. I believe I could become productive quickly using this system” and “17. I liked using the interface of this system” with average ratings of 1.2 points.

The worst items, given their higher average score, were “2. It was simple to use this system” and “11. The information provided with this system was clear”, both rated with 3 points, in average. These results suggest that participants were more satisfied with the prototype quality than the easiness and quality of information.

Evaluating the PSSUQ subgroups scores, the interface quality was the best result with an average of 1.73 points. With higher ratings, the system usefulness scored an average of 2.23 points whereas the information quality scored 2.4 points. In overall, the total average score from all the test items was 2.15, indicating a high prototype usability and that participants felt satisfaction while using the prototype.

ICF-US results

The average rates obtained for each of the ICF-US I items are presented in Fig. 6.

From an overall perspective, the prototype had a good reception from participants, and all found the application as a facilitator (all positive scores). Also, the average total score was 17.6, meaning that, in general terms, the prototype is a facilitator.

Examining each item individually, “1. The ease of learning” and “5. The similarity of the way it works on different tasks” were the items with higher score (2.4), confirming that the use of a simple interface with a similar layout for each page was a good decision. However, “6. the ability to interact in various ways” had the lowest score (0.4), and being a multimodal application this value is somehow intriguing since it differs greatly from the others. Although the prototype accepts interactions by using the speech modality, beyond the regular use of touch or a mouse, the only evaluation task that demanded participants to use speech was the quiz game section. But, and as stated before, almost all participants were not able to use speech to promptly answer the quiz question and finished the task by using touch. Therefore, the difficulty in using speech may be the explanation to the low usability score obtained for the item 6.

5.2 Participant Feedback

During the evaluation, from notes taken by the observers, and by talking to the participants, all the recommendations and personal opinions were registered so that, in future works, these points could be considered to improve the application. Suggestions included:

-

The system should allow the use of a frontal camera, if available;

-

The icons should be more appealing and intuitive;

-

To facilitate recognition, the icons in the edit panel should have captions;

-

The system should give feedback when an emotion is selected, placing the image corresponding to the selected emotion in the current photo;

-

When viewing the pictures stored on the device, in addition to the arrow keys, the system should allow swipe to scroll between photos;

-

The time required to use the speech modality, to answer a question in the quiz game, should be shorter;

-

In the diary, the section for entering comments should be called the “comment” instead of “answer”;

-

Accessing the notes panel should be more intuitive;

-

The main menu should contain a button to enable shutting down the application.

6 Conclusions

Even though, at this stage, we did not include children with ASD, in the evaluation, its outcomes were positive and provide important feedback, by a heterogeneous set of participants, to continue evolving the application. It is our expectation that the second iteration of the application will already be more suited for such an evaluation. Having detected the issues regarding speech interaction, at this stage, was an important aspect that, in an evaluation with autistic children would be a major drawback.

One of the important results, so far, is that the proposed application can now be explored as a base for assessing how children with ASD can profit from a multimodal interaction setting. For example, how well do these children take advantage of multimodality and how novel interaction modalities—such as gaze, which we just barely explored here—might bring increasing acceptance of the application or work as a tool to develop their competences.

References

Almeida, N., Silva, S., Teixeira, A.: Design and development of speech interaction: a methodology. In: Kurosu, M. (ed.) HCI 2014. LNCS, vol. 8511, pp. 370–381. Springer, Cham (2014). doi:10.1007/978-3-319-07230-2_36

AssistiveWare: Proloquo2go: symbol-based AAC for iOS – assistiveware. http://www.assistiveware.com/product/proloquo2go

Buzzi, M.C., Buzzi, M., Gazzé, D., Senette, C., Tesconi, M.: ABCD SW: autistic behavior & computer-based didactic software. In: Proceedings of the International Cross-Disciplinary Conference on Web Accessibility, W4A 2012, pp. 28:1–28:2. ACM, New York (2012)

Caronna, E.B., Milunsky, J.M., Tager-Flusberg, H.: Autism spectrum disorders: clinical and research frontiers. Arch. Dis. Child. 93(6), 518–523 (2008)

Chien, M.E., Jheng, C.M., Lin, N.M., Tang, H.H., Taele, P., Tseng, W.S., Chen, M.Y.: iCAN: a tablet-based pedagogical system for improving communication skills of children with autism. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 73, 79–90 (2015)

Cooper, A., Reimann, R., Cronin, D.: About Face 3.0: The Essentials of Interaction Design. Wiley, Indianapolis (2007)

Dumas, B., Lalanne, D., Oviatt, S.: Multimodal interfaces: a survey of principles, models and frameworks. In: Lalanne, D., Kohlas, J. (eds.) Human Machine Interaction. LNCS, vol. 5440, pp. 3–26. Springer, Heidelberg (2009). doi:10.1007/978-3-642-00437-7_1

Freitas, J., Candeias, S., Dias, M.S., Lleida, E., Ortega, A., Teixeira, A., Silva, S., Acarturk, C., Orvalho, V.: The IRIS project: a liaison between industry and academia towards natural multimodal communication. In: Proceedings of IberSPEECH, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, pp. 338–347 (2014)

Gay, V., Leijdekkers, P., Agcanas, J., Wong, F., Wu, Q.: CaptureMyEmotion: helping autistic children understand their emotions using facial expression recognition and mobile technologies. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 189, 71–76 (2013)

Kagohara, D.M., van der Meer, L., Ramdoss, S., O’Reilly, M.F., Lancioni, G.E., Davis, T.N., Rispoli, M., Lang, R., Marschik, P.B., Sutherland, D., et al.: Using iPods\({\textregistered }\) and iPads\({\textregistered }\) in teaching programs for individuals with developmental disabilities: a systematic review. Res. Dev. Disabil. 34(1), 147–156 (2013)

Leal, A., Teixeira, A., Silva, S.: On the creation of a persona to support the development of technologies for children with autism spectrum disorder. In: Antona, M., Stephanidis, C. (eds.) UAHCI 2016. LNCS, vol. 9739, pp. 213–223. Springer, Cham (2016). doi:10.1007/978-3-319-40238-3_21

Martins, A.I., Rosa, A.F., Queirós, A., Silva, A., Rocha, N.P.: Definition and validation of the ICF-usability scale. Procedia Comput. Sci. 67, 132–139 (2015)

Muñoz, R., Barcelos, T., Noël, R., Kreisel, S.: Development of software that supports the improvement of the empathy in children with autism spectrum disorder. In: Proceedings of 31st International Conference of the Chilean Computer Science Society, pp. 223–228, November 2012

Oviatt, S.: Advances in robust multimodal interface design. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 23(5), 62–68 (2003)

Quintela, M.A., Mendes, M., Correia, S.: Augmentative and alternative communication: Vox4all\({\textregistered }\) presentation. In: 2013 8th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), pp. 1–6. IEEE (2013)

Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center on Communication Enhancement: Mobile devices and communication apps. http://aac-rerc.psu.edu/index.php/pages/show/id/46

Ribeiro, V.S., Martins, A.I., Queirós, A., Silva, A.G., Rocha, N.P.: Usability evaluation of a health care application based on IPTV. Procedia Comput. Sci. 64, 635–642 (2015)

Rosa, A.F., Martins, A.I., Costa, V., Queirós, A., Silva, A., Rocha, N.P.: European Portuguese validation of the post-study system usability questionnaire (PSSUQ). In: Proceedings of the 10th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), pp. 1–5. IEEE (2015)

Sampath, H., Indurkhya, B., Sivaswamy, J.: A communication system on smart phones and tablets for non-verbal children with autism. In: Miesenberger, K., Karshmer, A., Penaz, P., Zagler, W. (eds.) ICCHP 2012. LNCS, vol. 7383, pp. 323–330. Springer, Heidelberg (2012). doi:10.1007/978-3-642-31534-3_49

Sennott, S., Bowker, A.: Autism, AAC, and proloquo2go. SIG 12 Perspect. Augment. Altern. Commun. 18(4), 137–145 (2009)

Silva, S., Almeida, N., Pereira, C., Martins, A.I., Rosa, A.F., Oliveira e Silva, M., Teixeira, A.: Design and development of multimodal applications: a vision on key issues and methods. In: Antona, M., Stephanidis, C. (eds.) UAHCI 2015. LNCS, vol. 9175, pp. 109–120. Springer, Cham (2015). doi:10.1007/978-3-319-20678-3_11

Teixeira, A., Almeida, N., Pereira, C., Oliveira e Silva, M., Vieira, D., Silva, S.: Applications of the multimodal interaction architecture in ambient assisted living. In: Dahl, D.A. (ed.) Multimodal Interaction with W3C Standards, pp. 271–291. Springer, Cham (2017). doi:10.1007/978-3-319-42816-1_12

Teixeira, A., Ferreira, F., Almeida, N., Silva, S., Rosa, A.F., Pereira, J.C., Vieira, D.: Design and development of medication assistant: older adults centred design to go beyond simple medication reminders. Univ. Access Inf. Soc. 1–16 (2016)

Vieira, D., Freitas, J.A.D., Acartürk, C., Teixeira, A., Sousa, L., Silva, S., Candeias, S., Dias, M.S.: “Read that article”: exploring synergies between gaze and speech interaction. In: Proceedings of the 17th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, ASSETS 2015, pp. 341–342. ACM, New York (2015)

Walker, D.R., Thompson, A., Zwaigenbaum, L., Goldberg, J., Bryson, S.E., Mahoney, W.J., Strawbridge, C.P., Szatmari, P.: Specifying PDD-NOS: a comparison of PDD-NOS, asperger syndrome, and autism. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 43(2), 172–180 (2004)

Acknowledgements

Research partially funded by IEETA Research Unit funding (UID/CEC/00127/2013) and Marie Curie Actions IRIS (ref. 610986, FP7-PEOPLE-2013-IAPP). Samuel Silva acknowledges funding from FCT grant SFRH/BPD/108151/2015.

The authors thank the participants in the evaluation and the collaboration of Professor Ana Isabel Martins, particularly during the evaluation process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Vieira, D., Leal, A., Almeida, N., Silva, S., Teixeira, A. (2017). “Tell Your Day”: Developing Multimodal Interaction Applications for Children with ASD. In: Antona, M., Stephanidis, C. (eds) Universal Access in Human–Computer Interaction. Design and Development Approaches and Methods. UAHCI 2017. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 10277. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58706-6_43

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58706-6_43

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-58705-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-58706-6

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)