Abstract

In this person-oriented study 722 adolescents and adults filled out formal characteristics of behaviour—temperament inventory, satisfaction with life scale and positive and negative affect schedule. Using k-means clustering we assigned them to four subjective well-being (SWB) types: (1) achievers—high satisfaction, positive affective balance; (2) aspirers—low satisfaction, positive affective balance; (3) resigners—high satisfaction, negative affective balance; (4) frustrated—low satisfaction, negative affective balance; and to four temperament types denoting patterns of stimulation control (1) sanguine: high stimulation processing capacity (SPC) and high stimulation supply (StS); (2) melancholic: low SPC, low StS; (3) phlegmatic: high SPC, low StS; (4) choleric: low SPC, high StS. We compared stimulation control dimensions between SWB types and compared counts of SWB types across four profiles of temperament. SPC and StS were highest among achievers and lowest among the Frustrated, with aspirers and resigners in between. We found a clear correspondence between well-being structures and temperament types (a) the most common temperament among achievers was the sanguine, suggesting that this is the ‘happy temperament’, (b) among the Frustrated it was the melancholic (the ‘unhappy temperament’), (c) among resigners it was the choleric, suggesting that this ‘overstimulated temperament’ results in high satisfaction at the cost of lower affective balance, (d) among aspirers it was the Phlegmatic, suggesting that ‘understimulated temperament’, results in a good affective balance but lower satisfaction. Configurations of temperament dimensions within individuals affect the whole structure of SWB and can explain incongruence between cognitive and affective components of SWB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Happiness is a universal human goal and being happy or leading a satisfying life is important for people across the world (Diener and Diener 1996). Naturally, this leads to questions about the predictors of individual well-being. Although happiness may be understood differently by different people (Bojanowska and Zalewska 2015), and there are different operationalizations of the concept of happiness within psychological research (see Ryff 1989; Keyes 2002), a significant variance in its levels stems from stable personality factors (DeNeve and Cooper 1998). The ‘happy personality’ (Costa and McCrae 1980) consists of low Neuroticism and high Extraversion, suggesting that it is in part biologically determined. This claim, however, calls for additional research into the relationships between various conceptualizations of well-being, such as the subjective well-being (Diener 2000) and other stable traits, also those that refer to individual differences in stimulation regulation—the ‘how’ of the behaviour and not the ‘what’ (Kandler et al. 2012). These traits have been discussed in the regulative theory of temperament (Zawadzki and Strelau 1997) and the present study shows how they interact to create a ‘happy temperament’.Footnote 1 We do not analyze individual traits but their whole configurations in order to show, that an interaction of traits within individuals is vital to understanding the mechanisms underlying subjective well-being. Furthermore, we consider subjective well-being also in terms of whole configurations. This approach is underrepresented in current research and there is a dearth of studies into well-being types, since usually well-being is analyzed through its separate dimensions. In the present article, we examine links between four subjective well-being types (high/low affective balance and high/low satisfaction) and four temperament types (high/low stimulation processing capacity and high/low stimulation supply).

1.1 Regulative Theory of Temperament and Temperament Typology

Temperament is usually defined as a set of stable characteristics of behaviour and originally there were attempts, with more or less success, to differentiate temperament from personality by focusing on the proportion of genetic components responsible for its variabilities (DeYoung and Gray 2009). As stated by McCrae and colleagues (2000), when temperament is defined as a biologically based tendency, it seems very similar to personality, mostly because personality traits have recently been shown to carry a significant genetic component. With this approach temperament has mostly been studied among young children (Thomas and Chess 1977; Rothbart 1981). There are, however, different approaches to studying and defining temperament, mainly stemming from the Pavlovian biological approach. These conceptions stress not only the biological determinants of individual differences in behaviour but also the stylistic and energetic aspects of behaviour regulation as opposed to content-related aspects of behaviour found in personality dimensions (Kandler et al. 2013). The differentiation between personality and temperament in this approach focuses on showing its two distinct features. Firstly, it refers to formal aspects of behaviour and not content-related, concentrating on the ‘how’ of behaviour and not the ‘what’. For instance, it asks how fast a person does things, because at its core, temperament is a behavioural expression of qualities of the nervous and endocrine systems’ abilities to respond to stimulation, including pace (with little interest in its content, Strelau 2008). Secondly, these conceptions stress stimulation regulation as the core of temperament’s function. In classical personality descriptions, for example in Eysencks’ conception, a trait denoted the need and the tendency to fulfil this need—high extroversion would denote both the need for stimulation and the tendency to seek more stimulation through energetic efforts. With regulative theory of temperament these two dimensions are separate—one dimension is responsible for the need for stimulation (labelled stimulation processing capacity) and the other is responsible for supplying stimulation (labelled stimulation supply).

Strelau’s regulative theory of temperament (Strelau and Zawadzki 1995; Strelau 2008) originally lists 6 traits of temperament, but referring to Jankowski and Zajenkowski (2009) we will consider only four of them. These four traits determine how much stimulation a person can supply and processFootnote 2:

-

(1)

Emotional reactivity (ER): tendency to react intensively to emotion generating stimuli, expressed in high emotional sensitivity and in low emotional endurance;

-

(2)

Endurance (EN): ability to react adequately in situations demanding long-lasting or high stimulative activity and under intensive external stimulation;

-

(3)

Briskness (BR): tendency to react quickly, to keep a high tempo of performing activities, and to shift easily in response to changes in the surroundings from one behaviour (reaction) to another;

-

(4)

Activity (AC): tendency to undertake behaviour of high stimulative value or to supply, by means of behaviour, strong stimulation from the surroundings; (Strelau and Zawadzki 1995; Strelau 2008).

These traits regulate a wide array of behaviours, from the choice of preferred environments, to interpretations of stimuli (Strelau 2008), they refer to formal aspects of behaviour, in that all behaviour can be described with regard to its energetic and temporal characteristics (Strelau and Zawadzki 1995, see also a summary of the conception in Kandler et al. 2013). They are also an expression of the abilities of the human nervous system—the ability to process stimulation in an effective way and the ability to supply a lot of stimulation through energetic efforts.

The above four temperament traits come together to create two dimensions of temperament: stimulation processing capacity and stimulation supply. According to Zawadzki and Strelau (1997) and Jankowski and Zajenkowski (2009) the procedure for determining which temperament type a person most likely represents starts with computing these two dimensions. Emotional reactivity (inversed) and endurance determine stimulation processing capacity (SPC), while activity and briskness determine stimulation supply (StS). We include briskness into StS because the high tempo of activities means supplying a person with greater stimulation. However, this trait may be also considered as a component of SPC due to fast adaptation to changes in the surroundings and this demands high capacity for processing stimulation. According to the work of Jankowski and Zajenkowski, who proposed algorithms for computing SPC and StS, both indices have good psychometric qualities and can be used to determine individual temperament types (2009).

Interactions of these two dimensions (high/low SPC and high/low StS) produce four temperament types, that can be labelled similarly to the classic Hippocratic division. These Hippocratic labels have already been used by Pavlov in 1938 (see Strelau 2008) to denote temperament types. The regulative theory of temperament is based on the biological, Pavlovian approach and the authors adapted this labelling to denote temperament types derived by computing the relationships between SPC and StS. These dimensions can be harmonised (high SPC-high Sts or low SPC-low StS) or non-harmonised (low SPC-high StS or high SPC-low StS):

-

(1)

The sanguine: harmonised type with high SPC and high StS—high activity and briskness supply a lot of stimulation, while high endurance and low emotional reactivity allow for a high processing capacity.

-

(2)

The melancholic: harmonised type with low SPC and low StS—low activity and briskness supply little stimulation and this is congruent with low processing capacity stemming from low endurance and high emotional reactivity.

-

(3)

The phlegmatic: non-harmonised type with high SPC and low StS—high endurance and low emotional reactivity combined with low activity and briskness.

-

(4)

The choleric: non-harmonised type with low SPC—high activity and briskness, low endurance and high emotional reactivity.

1.2 Reported Effects of Temperament Traits on Well-Being

The direct role of these four temperament traits listed in regulative theory of temperament have been reported only in a few studies. Briskness is associated with less long-term PTSD (Zawadzki and Popiel 2012) and burnout symptoms (Rzeszutek and Schier 2014), similarly to endurance (Cieslak et al. 2008). Activity is connected to a more advantageous mood profile (Jankowski and Zajenkowski 2012; Wytykowska 2012). Low emotional reactivity helps cope with illness (Heszen 2012), moderates stress appraisal (de Pascalis et al. 2003; Fruehstorfer et al. 2012) and is linked to job satisfaction (Zalewska 2011). One study directly showed that emotional reactivity predicted better subjective well-being (greater satisfaction and positive affect and lower negative affect; Bojanowska and Zalewska 2011).

These traits, however, are also correlated with big five dimensions known for their significant impact on subjective well-being (Strelau and Zawadzki 1995, see also: Kandler et al. 2012) and basing on these correlations we may hypothesise how temperament traits impact subjective well-being. The functions of these traits, as well as their correlations with the big five suggest that they may be connected to the experience of well-being. These correlations from original validity studies have been presented by Strelau and Zawadzki (1995). Inferences may be drawn from the directions of these correlations. If (a) lower neuroticism and higher extraversion predict better well-being indices (Costa and McCrae 1980; DeNeve and Cooper 1998) and (b) higher briskness, endurance and activity, and lower emotional reactivity are connected to lower neuroticism and higher extraversion (Strelau and Zawadzki 1995), then (c) these traits may be also connected to better subjective well-being. The studies mentioned above, as well as studies on big five and subjective well-being analyze the roles of specific traits for various opertionalizations of well-being, but rarely do researchers analyze configurations of individual traits within individuals (typological approach). There are no studies linking types of stimulation control (that is the core of RTT’s definition of temperament) to well-being. There have, however, been some investigations of the impact of personality types on well-being. For example, Scholte et al. (2005) reported that personality types were associated with very distinct adjustment patterns.

Other traditions of studying temperament also showed that stable, genetically determined individual characteristics bear strong links to well-being. Top–down models suggest that individuals have a global tendency to experience life in a positive or negative way (DeNeve and Cooper 1998), affective balance can in fact be treated as a dispositional trait (Garcia and Moradi 2013) and that experienced well-being has strong dispositional determinants (Chamorro-Premuzic et al. 2007). Costa and McCrae (1980) suggested that the mechanism underlying the relationship between personality and subjective well-being was connected to temperament. From this perspective, extroverts are more cheerful and high spirited in comparison to introverts, and emotional instability facilitates the experience of negative emotions. This explanation may point to the link between Subjective Well-being and its biological determinants. Tellegen et al. (1988) indicated that its affective component depends on genetic factors but that the explained variance is bigger for negative affect (55 %) than for positive affect (40 %). Newer studies also pointed out that heritable factors are responsible for the levels of individual well-being up to 50 % of variance (Bartels and Boomsma 2009).

1.3 Subjective Well-Being Typology

There are numerous approaches to positive functioning. Some focus on eudaimonic happiness and delineate areas such as personal growth or positive relationships as vital to psychological well-being (Ryff 1989). Other draw from health models and the good life as a syndrome of positive feelings and positive functioning in life (Keyes 2002). These approaches, however, decide a priori the dimensions of positive functioning (Torras 2008). Subjective well-being conception, on the other hand, despite being criticized for a lack of theoretical grounding (Ryff 1989), assumes that it is the individual, who is the best judge of his or her own well-being. In this approach, subjective well-being is a multi-faceted concept and it consists of the affective component (positive and negative affect) and cognitive component (life satisfaction; Diener 2000). These two components are not always congruent with one another (Klonowicz 2001; Lucas et al. 1996; McKennell 1978; Zalewska 2004) and correlations between them are far from ideal. Therefore, also in terms of Subjective Well-being, people can be divided into types (McKennell 1978):

-

(1)

Achievers—satisfied individuals with a high positive affective balance;

-

(2)

Aspirers—unsatisfied individuals with a high positive affective balance;

-

(3)

Resigners—satisfied individuals with a negative affective balance;

-

(4)

The frustrated—unsatisfied individuals with a negative affective balance.

We compare these four types with regard to temperament types conceptualized in regulative theory of temperament (Strelau and Zawadzki 1995; Strelau 2008).

1.4 The Typological Approach

It seems that the study of types is much neglected in recent publications. Researchers focus on the effects of separate dimensions (or traits) and neglect to analyze the impact played by these traits’ interactions and their possible joint influence on well-being. The first big question, therefore, is how to define a ‘type’. Two schools can be found in recent publications—we label them ‘prototypical’ approach and ‘extreme type’ approach (similar label was used by Wytykowska 2012). The first, found for example in Asendorpf et al. (2001) aims to discover prototypes, clusters of trait levels that keep appearing in various datasets, suggesting an underlying dimension responsible for such configurations. Studies using this approach resulted in the identification of replicable personality types, based on the big five (resilient, overcontrolled and undercontrolled). The second, the ‘extreme type’ approach, has been proposed by Pavlov in reference to temperaments (1938, in: Strelau 2008), and by McKennell (1978) or Shmotkin et al. (2006) in reference to subjective well-being. In this ‘extreme type’ approach, the idea is not to prove that prototypes exist (they are pre-defined), but to show how various configurations of traits impact other dimensions. The theoretical assumptions place the most fitting representatives of these types at the intersection of very low and high scores of dimensions.

The typological approach has also been labeled ‘person oriented’ and ‘one of the most important arguments or considering type perspective instead of trait perspective is the idea that clusters may capture some important information concerning personality which is not provided by the dimensions alone’ (Wytykowska 2012, p. 228). As stated by Asendorpf, ‘the variable-oriented approach misses an important aspect of personality, namely the intra-individual configuration or profile of personality dimension (…) If the variable-centered approach describes the building blocks of personality, the person-centered approach describes the building.’ (2002, p. 259). Additionally, this approach can facilitate the search for moderator variables in intra-individual structure of traits (Avsec et al. 2015).

Authors that focus on this person-oriented approach in reference to well-being stress that individual patterns of components of well-being within a person are informative in that they denote individual adaptation (Shmotkin et al. 2006) and because they inform of the organization and structure of traits within individuals (McKennell 1978). As shown by these authors, the consequences of such configurations, especially when there is an incongruence between affective and cognitive components, are essential in understanding mechanisms underlying subjective well-being. In reference to temperament, typological approach reflects the essence of regulative theory of temperament—combinations of traits within a person denote the effectiveness of stimulation control (Wytykowska 2012). Only after comparing dimensions responsible for various aspects of stimulation control is it possible to estimate the effectiveness of this regulation (Strelau 2008).

1.5 The Present Study

In the present study we aim to expand the concept of the ‘happy personality’ in two ways. Firstly, we show how temperament (formal characteristics of behaviour denoting effectiveness of stimulation control), can be used to explain differences in subjective well-being. Temperament is linked to personality, originally it was differentiated from personality though the proportion of genetic impact on its variability (saying that temperament is more stable than personality; see discussion in McCrae et al. 2000). However, in regulative theory of temperament this is not the main distinct characteristic of temperament, although its genetic rooting and stability are an important element of the conception. Instead, what differentiates temperament from personality lies mostly in the formal, stylistic and energetic aspect of temperament traits (Strelau 2008). Temperament traits described in regulative theory temperament denote energetic and temporal regulation of behaviour—stable patterns of dealing with stimulation, regardless of its context. Mechanisms governing this regulation are linked to human physiology. Secondly, we aim to show that not only do its general dimensions impact subjective well-being, but their whole configurations may be used to explain subjective well-being structure. This can only be done in type-oriented studies.

Basing on the functions of temperament traits constituting SPC and StS dimensions, we hypothesise, that (H1) SPC and StS are highest among achievers and lowest among the frustrated, with aspirers and resigners in between. There is no data to predict which dimensions—SPC or StS—are linked to the dimensions of well-being (affective balance or satisfaction), so we cannot predict the levels of these composite dimensions among aspirers and resigners (Q1).

We suspect, that the four types of temperament are linked to the four types of subjective well-being. Basing on the functions of temperamental dimensions constituting these types, we suspect, that (H2) the most common temperament among the achievers is the sanguine—highest subjective well-being is experienced by those, who can process a lot of stimulation (high SPC) and supply a lot of stimulation (high StS) and (H3) the most common temperament among the frustrated is the melancholic—the lowest subjective well-being is experienced by those, who cannot process a lot of stimulation (low SPC) and supply little stimulation (low StS).

We, however, do not know which temperament types are most common among the resigners and aspirers, because the structure of their subjective well-being is complex. Possibly, they correspond to the two other temperament types, but we do not know to which (Q2).

We also posed an additional question on whether the relationships between temperament types and subjective well-being types is universal in terms of age—in other words, if age moderates these relationships (Q3). This study does not focus on developmental aspect of these relationships, but to maintain the reliability and validity of the findings we must investigate if these effects are age dependant.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants (N = 722) were Polish people aged from 13 to 45 years-old, uneven distribution, groups were aged 13–14: n = 168; 17–18: n = 201, 28–33: n = 195, 40–45: n = 158). In each group half of the participants was living in a big city (Warsaw) and the others in small town (Mielec). All adolescents attended schools and all adult participants had jobs. There was a close to even distribution of women and men (women/men: 13–14: 54/46 %; 17–18: 40/60 %; 28–33: 53/47 %; 40–45: 56/44 %).

2.2 Procedure

Among teenagers we conducted the study in class with the teacher present. Among adults the questionnaires were distributed in the workplace (after getting permission from a manager or Human Resources Department) and a deadline for return (in a sealed envelope) was set. The participants were informed, that the study was anonymous and voluntary.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Formal Characteristics of Behaviour: Temperament Inventory

Temperamental traits were measured using formal characteristics of behaviour—temperament inventory (Strelau and Zawadzki 1995; Zawadzki and Strelau 1997). This is a valid and reliable tool. Original validity studies indicated, that the questionnaire has a good factor structure and internal consistencies (alphas of above .7), with normally distributed scores in the validity sample of 2000 persons (skewness and kurtosis ranged between <−1, 1>). Traits show a strong temporal stability, correlation coefficients ranged between .7 and .8 after 6 months. The traits correlated with some of the big five dimensions (e.g. Briskness at .29–.45 with neuroticism and extraversion, emotional reactivity at .6 with neuroticism and .25 with extraversion, endurance at .3–.5 with neuroticism and .2 with extraversion; and activity at .2–.3 with neuroticism and .6 with extraversion) These traits were briskness (e.g. I usually manage to jump aside so as not to be splashed by a passing car), emotional reactivity (e.g. I often break down in difficult moments), endurance (e.g. I can work intensively after a sleepless night), and activity (.e.g. I try to organize holidays to experience as much as possible).Footnote 3 There were 20 items for each trait, with yes/no answers (scores range from 0 to 20). All subscales in this measure reached sufficient reliability (alphas above .76).

2.3.2 Subjective Well-Being Indices

Positive and negative affect were measured using positive and negative affect schedule (Watson et al. 1988) translated into Polish with a back-translation. The measure includes a list of 10 adjectives referring to positive (e.g. interested, excited) and 10 to negative affective states (e.g. guilty, ashamed) and respondents were asked to indicate how intensely they had felt this way during 2 weeks before the study. The scale ranged from 1 (only slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely) and the measure reached sufficient reliability (see Table 1).

Satisfaction with life was measured using satisfaction with life scale (Diener et al. 1985). Participants indicated to what extent they agreed with the statements about their lives (e.g. in most ways my life is close to my ideal) on a scale from 1 (I definitely disagree) to 7 (I definitely agree). Higher scores meant better life satisfaction. The measure reached sufficient reliability (see Table 1).

2.4 Statistical Procedure for Deriving Types

We chose K-means clustering to derive types. It seems to be the best choice for the ‘extreme type’ search presented in our paper, because the K-means clustering is a test of the biggest difference (looks for the least similar cases first). This stems directly from the theoretical assumptions underlying this study. We use the ‘extreme type’ approach, as opposed to the ‘prototype’ approach since our main aim was to assign participants to a set of theoretical types of temperament and subjective well-being. For example, Strelau (2008, similarly to Pavlov) describes the types as theoretical interactions between extreme scores of the dimensions constituting a given type. Consequently, in this approach the ‘perfect’ sanguine would score extremely high on stimulation processing capacity and stimulation supply, while a ‘perfect’ choleric would score extremely high on stimulation supply, and low on stimulation processing capacity. It would be possible to identify individuals that best represent these extreme types in data sets, but due to normal distributions of scores of SPC and StS, most people fall somewhere in between. Therefore we need to compromise and assign individuals to types using clustering procedures. A similar procedure, or even more extreme in terms of contrasting types, was used by McKennell (1978), when he discussed the four types of subjective well-being. He dichotomized the two dimensions of subjective well-being and then used a 2 × 2 categorization to see which other variables change diagnostically between cells (more recently also used by Shmotkin et al. 2006). In our sample this was not necessary, because clustering produced types well differing in terms of the analyzed dimensions (SPC, StS for temperament; affective balance and satisfaction for subjective well-being). Both Strelau’s and McKennell’s aim was to contrast the types as much as possible, so that consequences of incongruence between SPC and StS for the affective and cognitive well-being would be easy to investigate. To deal with drawbacks of the clustering procedure, we computed Cohen’s ϰs for participants randomly split into halves (similarly as done by Asendorpf et al. 2001). The agreement ranged from .7 to .9, indicating good agreement between clusters created for split datasets.

3 Results

All analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 20.0 software (IBM Corp. 2011). For both clustering procedures we chose K-means clustering. K-means seemed most fitting to the purposes of our analyses because it maximizes differences between groups (see Sect. 1.4 for a discussion of this rationale).

3.1 Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics of the main variables. All variables are weakly to moderately correlated. All scales reached sufficient reliabilities.

3.2 Data Reduction: Temperament Profiles

K-means clustering with K = 4 produced clusters corresponding to Strelau’s (2008) typology of temperament and they are labelled according to the classic hippocratic division. Comparisons of temperament dimensions levels further confirmed that these clusters fit the intended temperament types (see Table 2).

3.3 Data Reduction: Types of Subjective Well-Being

Mean answers in positive and negative affect schedule were computed to produce indices of positive and negative affect. Positive affect index was then divided by negative affect index to produce affective balance index, which was then standardized (higher index meant more positive affective balance). Mean answers to all items in satisfaction with life scale were computed to produce an index of satisfaction, which was then standardized. K-means clustering with K = 4 produced clusters corresponding with four subjective well-being structures (types) proposed by McKennell (1978). Clusters differed in terms of affective balance, positive and negative affect, and satisfaction (see Table 3).

Resigners experience a negative affective balanceFootnote 4 and a high level of satisfaction. Aspirers experience a positive affective balance and low satisfaction. The frustrated experience negative affective balance and low satisfaction. Achievers experience positive affective balance and high satisfaction.

3.4 Stimulation Processing Capacity and Stimulation Supply in Four Well-Being Types

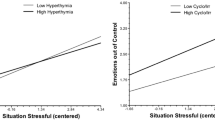

Using ANOVA comparisons (Table 4) we managed to confirm (H1). SPC and StS were highest among achievers and lowest among the frustrated, with aspirers and resigners in between. The analysis also showed (Q1), that SPC was lower among resigners (high satisfaction and negative affective balance) than aspirers (low satisfaction and positive affective balance) and there were no differences in StS between resigners and aspirers.

3.5 Do Temperament Types Correspond with Types of Subjective Well-Being?

We used χ2 to verify distributions of the four temperament profiles across four types of subjective well-being. The results are displayed in Table 5. As stated in hypotheses 2 and 3, the most common temperament among the Achievers was the sanguine—the highest indices of subjective well-being are observed among those, who can process a lot of stimulation and supply a lot of stimulation—and the most common temperament among the frustrated was the melancholic—the lowest indices of subjective well-being are observed among those, who cannot process a lot of stimulation and supply little stimulation.

We also managed to answer Q2, in that the most common type among the resigners was the choleric, among the aspirers it was the phlegmatic. This means satisfied individuals with a negative affective balance can supply a lot of stimulation but are unable to process it (overstimulation), while unsatisfied individuals with a positive affective balance are able to process a lot of stimulation but do not supply it (understimulation).

3.6 Are the Effects Age Dependant?

We also verified the persistence of these effects over age groups—we aimed to verify if the correspondence between temperament types and subjective well-being types was specific to age groups or if it was more universal.

First we compared mean levels of affective balance, satisfaction, stimulation processing capacity and stimulation supply between age groups (see Table 6). This analysis showed differences in affective balance, stimulation processing capacity and stimulation supply. Since, these dimensions did not follow similar patterns, we conducted an additional analysis, to verify if this dynamic impacts the relationships between subjective well-being and temperamental dimensions.

We conducted a regression analysis, where we introduced age (‘dummy’ coded with 0–1), stimulation processing capacity and stimulation supply in the first step and interaction terms in the second step. These interactions terms were computed as the products of each ‘dummy’ coded age variable with stimulation processing capacity and with stimulation supply, separately. We conducted this analysis separately for satisfaction and for affective balance. The aim of this analysis was to verify if age moderates the relationship between temperament and subjective well-being. This analysis showed no interaction effect—for both dependent variables (satisfaction and affective balance) the R 2 change was insignificant for the second step (F change = 1. 67; p > .05; F change = 1. 64; p > .05).

Third, we compared the distribution of temperament types across Subjective Well-being types (Table 7). χ2 statistic was significant in all groups, suggesting relationships between types of subjective well-being and types of temperament were present in all age groups. A closer investigation also showed that the correspondence between temperament types and subjective well-being types persisted over age in almost all groups. In all age groups the sanguine type was most common among the achievers, the melancholic among the frustrated and the choleric among the resigners. The phlegmatic type was most common among the aspirers in groups of adolescents. The only two groups where only this particular configuration was not observed were young adults (among the aspirers the sanguine type was the most common and among the phlegmatic there was a smaller than expected number of aspirers and achievers) and in mid-life (as many aspirers as achievers, a slight overrepresentation of these types).

The general effects observed for the whole group seem valid and reliable but there may also be a developmental aspect worth investigating in reference to the phlegmatic. For this type, the difference in observed counts of subjective well-being types between adolescents and adults points to a possible dynamic of the functions played by StS and SPC configurations. These differences, may however, be an artefact of the small numbers of participants for some cells—as low as 1 person.

4 Discussion

In the present study we analyzed the relationships between Subjective Well-being as conceptualized by Diener (2000; positive affect, negative affect and satisfaction with life) and two dimensions of temperament—stimulation processing capacity (SPC) and stimulation supply (StS) (Strelau 2008). We used a typological approach to show how four subjective well-being types (the frustrated, resigners, aspirers and achievers; McKennell 1978) correspond to four types of temperament (sanguine, melancholic, phlegmatic, choleric). We aimed to show, that there are temperamental configurations, that constitute a ‘happy temperament’, but there are also other types, connected to other subjective well-being configurations. This would not be possible if we used only the variable-oriented approach, because individual temperament dimensions in the four types of subjective well-being cannot explain the observed incongruence between its affective and cognitive components.

4.1 Temperamental Dimensions and Subjective Well-Being Structure

We managed to confirm (H1) that stimulation processing capacity (SPC) and stimulation supply (StS; Strelau 2008) are highest among achievers and lowest among the frustrated (McKennell 1978). This means that with high SPC it is easier to function in general—a person with a strong, enduring nervous system with low emotional reactivity can function without additional cost of processing a lot of stimulation. This may directly enhance affective balance through lowered emotional reactivity (which limits negative interpretations of incoming stimuli) and through higher endurance (which helps a person feel better in a wider array of circumstances, also when the stimulation is high). This leads to a better distribution and conservation of resources, possibly to better performance and consequently to greater satisfaction. Achievers, with a congruent, positive structure of subjective well-being also have highest indices of stimulation supply. Through higher activity they engage in more tasks, and therefore they have more positive experiences and they can also adapt quicker to changing circumstances through higher briskness.

We also investigated (Q1) the levels of these two dimensions among resigners and aspirers. Our data showed that SPC was lower among resigners than aspirers, whereas these two groups did not differ in terms of StS, which was close to an average level. This suggests, that the price paid for lower SPC, when StS is average, lies mostly in lowered affective balance but the benefit of such a configuration is a higher satisfaction. At the same time, higher SPC with average StS can possibly lead to a lower satisfaction but accompanied by a positive affective balance. These interpretations, however, need to be supplemented with a discussion of whole configurations of temperament types (below), because SPC in itself may have a different impact on subjective well-being when accompanied by different levels of StS.

4.2 Happy Temperament?

We found that the ‘happy temperament’ is the harmonised high SPC type (high SPC combined with high StS), the sanguine according to Hippocratic typology (Strelau 2008). This temperament configuration is the most common for achievers, who experience a high level of satisfaction and a positive affective balance. This means that the way the sanguine process and supply stimulation is optimal for a high quality of life. In this type, there are no issues with processing a lot of stimulation, so people can function effectively in a wide array of circumstances, including those with a high stimulation value. It also means, that a high SPC combined with the ability (and preference) to supply a lot of stimulation gives lots of opportunities for positive experiences. This type has it all—the preference for active lifestyles, the ability to shift between tasks quickly, a tendency for positive evaluations of stimuli and a high endurance. These two dimensions (SPC and StS) in this type are in congruence and they are linked to a congruent, positive subjective well-being structure. Achievers engage in more activities and can maintain their activity for long periods of time, while at the same time their emotional reactions are weaker, especially the negative ones, and so their interpretations of emotional stimuli are more positive in comparison to people with higher emotional reactivity (Strelau 2008; Zalewska 2003). This suggests, that achievers gain a lot from their numerous activities, leading to greater satisfaction and a positive affective balance.

On the other hand, there is the ‘unhappy temperament’, a combination of low SPC and low StS, most common for the Frustrated. This type, called the harmonized low SPC type, or the melancholic type (Strelau 2008) is especially burdened with a disadvantageous trait configuration—a tendency to interpret stimuli in a negative way (high emotional reactivity), lower endurance leading to tiredness and negative affective states, a tendency to avoid stimulation (low activity) and slow reactions to changing circumstances, that may lead to an ineffective resource management (low briskness). The effect of this configuration for well-being is pessimistic, as it leads to a congruently negative subjective well-being structure with low satisfaction and a negative affective balance, despite the harmony between SPC and StS. In this group temperamental regulatory functions possibly lead to engaging in a smaller number of activities for shorter periods of time, because the nervous system in this type is unable to withstand a lot of stimulation. Since temperament plays a regulatory function for behaviour (Strelau 2008), it would seem that with this harmony melancholics may be able to find activities and occupations that suit their (low) stimulation needs. However, the challenges of the contemporary world and social norms promoting ambition and activity as the proper way of functioning, may prevent this group from finding a suitable niche with low stimulation.

We also found the ‘overstimulated temperament’. The most common temperament structure for the resigners was the non-harmonised low SPC type, also labelled the choleric type (Strelau 2008). This type has low SPC but average or above average StS and this means that people with this configuration tend to become overstimulated. They are active and brisk, so they supply too much stimulation to process it effectively or they process it at too great a cost. Consequently, this overstimulation results in an incongruent subjective well-being structure. With this temperament configuration people may experience a high satisfaction level, because they engage in a lot of activities, but they pay for their activity with a decreased affective balance. In general, this lack of harmony between SPC and StS leads to lack of harmony in well-being. Overstimulation may help maintain satisfaction, but at a cost of unfavourable emotional balance.

Lastly, we found the ‘understimulated temperament’, people with high SPC and low or below the average StS. This is the non-harmonised high SPC type or the phlegmatic (Strelau 2008) most common for aspirers. In this temperament configuration, people tend to get (supply) too little stimulation in relation to their processing capacities. Therefore, they experience a positive affective balance, because they are not burdened with unnecessary stress, but they have low satisfaction. Possibly, this group avoids stimulation (challenges) and pays for ‘relaxed’ lifestyles in low satisfaction, because they have too little experiences that may bring satisfaction. Also, modern social norms (in this study: in Poland) tend to promote ambition and activity and therefore people, who do not meet modern standards may feel dissatisfied when they compare themselves to others in their surroundings.

These effects can be referred to other data on individual differences and subjective well-being. Through the correlations between temperament and big five and some overlap between the functions of their dimensions, inferences can be drawn from this study for the expected outcomes of personality types for subjective well-being. As stated in the introduction ‘happy personality’ has been described as high extraversion and low neuroticism (Costa and McCrae 1980). Emotional reactivity and endurance have strongest correlation to neuroticism, so their effects on subjective well-being are possibly similar. These dimensions share a common characteristic—they refer to the tendency for negative emotionality (neuroticism and emotional reactivity) or a decrease in positive emotions in face of high stimulation (neuroticism and low endurance). Activity, on the other hand, has also some overlap (and a positive correlation) with extraversion, with only moderate correlations between extraversion and briskness. These correlations and the overlap in functions suggest, that the ‘happy temperament’ has similar effects for subjective well-being as the ‘happy personality’, and that the ‘unhappy temperament’ has similar effects as the ‘unhappy personality’ (low extraversion and high neuroticism). However, these direct links would be difficult to explain for the ‘over-’ and ‘understimulated’ temperaments because the relationships between stimulation processing capacity and stimulation supply is not the same as the relationship between extraversion and neuroticism—the latter pair does not inform of over or understimulation. At best, there would be some overlap between the ‘understimulated type’ and a configuration of low neuroticism and low extraversion. This configuration may not be typical among aspirers, but it may be linked to some other subjective well-being structure (possibly not included in McKennell’s categorization)—possibly with a low negative emotionality and lower satisfaction (through lower neuroticism) and low positive emotionality (through lower extraversion; see: DeNeve and Cooper 1998 for an overview). Similarly, the ‘overstimulated type’ may share similarities with high extraversion and high neuroticism configuration. With this configuration the negative affect is increased and satisfaction is decreased (through higher neuroticism) but also the positive affect is increased (through higher extraversion) so the effects for affective balance may be different than found for the ‘overstimulated’ temperament.

Despite observed differences in the levels of affective balance, stimulation processing capacity and stimulation supply between age groups, these effects were mostly universal. Age did not moderate the relationship between temperament type and subjective well-being type, the links were similar in almost all age groups. Quite possibly, these regulative functions of temperament dimensions impact subjective well-being in a steady way. The levels of SPC and StS may have a developmental dynamic, but if we consider their intersections (which produce the four types), their links to subjective well-being types are also similar in age groups. These observations indicate that the stimulation regulation is a basic, stable mechanism, that accompanies an individual at least until the mid-life period (this is the age range covered in our study). On the other hand, the general effects observed for the whole group were different in reference to the phlegmatic type. In young adult groups resigners and the frustrated were slightly overrepresented in the phlegmatic type, while in mid-life this type had a slight overrepresentation of aspirers and achievers. Possibly, the relative lower stimulation supply typical among the phlegmatic is disadvantageous for satisfaction levels of adolescents, but for adult groups other mechanisms may take over. This, however, requires additional research focusing on the developmental perspective.

5 Conclusions

There are clear links between stylistic, formal characteristics of behaviour that are vital in temporal and energetic regulation and subjective well-being. The four types of temperament correspond to four types of subjective well-being: the sanguine experience congruent, positive SWB, the melancholic experience congruent negative SWB, the choleric maintain high satisfaction but at the cost of lowered affective balance, and phlegmatic maintain a good affective balance at the cost of lowered satisfaction.

Similarly to ‘happy personality’, consisting of high extraversion and low neuroticism, high SPC and high StS help experience high levels of subjective well-being. However, the ‘happy personality’ concept (Costa and McCrae 1980) has only been analyzed in the dimensional approach and not as a configuration. It basically says, that low neuroticism is better for well-being and that high extraversion is better for well-being, but it does not analyze how the interplay of those traits impacts well-being. Consequently, there is a dearth of knowledge on the impact of interactions of traits on well-being. We attempted to fill this gap but we used categories of temperament (as opposed to personality), which focus on the energetic, stylistic and formal aspects of behaviour (Zawadzki and Strelau 1997), the ‘how’ people tend to do things and not to the ‘what’. Additionally, temperament as conceptualized in the regulative theory of temperament (as opposed to most personality conceptions) allows for the analysis of the regulative functions of traits—the relationship between the need for stimulation and preferred activity levels that fulfil this need. This could not be done using conceptions of personality, because these two areas (need and supply) are joined within one trait. For example, high extroversion would denote both the need for stimulation and the tendency to seek more stimulation through energetic efforts (similarly to neuroticism in reference to emotional stimulation). In RTT these two functions are expressed through two dimensions—stimulation processing capacity and stimulation supply—so the regulation lies in their mutual relationships. Our analysis clearly showed, that there are configurations that can be called ‘happy’ and ‘unhappy temperament’ but also, that there are two intermediary types—the ‘understimulated’ and the ‘overstimulated’ temperaments which result in incongruent subjective well-being structure. All these configurations of temperament are vital to the structure of subjective well-being.

Stylistic, formal aspects of behaviour regulation may have serious consequences for subjective well-being. Specific, disadvantageous, trait configurations put individuals at risk of lowered indices of subjective well-being. This study indicates, that the negative consequences of overstimulation lie mostly in emotional functioning, while the cost of understimulation lies in decreased satisfaction. Still, over- and understimulation proved to be more advantageous than stimulation control among the melancholic, who do not supply stimulation but at the same time they would not withstand a lot of it. This last group experiences the lowest subjective well-being in all of its components. There is, however, one group—the sanguine—who clearly show an advantageous temperamental configuration. The way that the sanguine deal with stimulation, through energetic and temporal regulation, helps them experience a congruent, high subjective well-being. Because of the genetic basis of temperament and its strong stability, we also see implications of this for practice. We know, that temperaments cannot be changed (or it takes years, Strelau 2008) but they can be used as a base of building other resources. Positive psychotherapists claim that identifying and building resources may be more effective than addressing deficits (Trzebinska 2008). We identified these resources among the sanguine (both areas of stimulation regulation), the phlegmatic (strong stimulation processing capacity) and the choleric (strong stimulation supply). However, for the melancholic there seem to be little in terms of stimulation regulation that can help in building a good life, therefore for these individuals we must look for other, possibly more relational or value-oriented approaches to building individual resources.

6 Limitations

The sample was entirely Polish so the detected effects might be limited to the Polish society. The study covered only the first half of life, so some of the effects might pertain only to younger people. There are also limitations to the typological approach. The person-oriented approach does not usually present stronger predictions than dimension-oriented (see: Avsec et al. 2015), the predictions from this study may also be moderate, but they show more complex functions of intraindividual temperament structure. Also, as stated by Asendorpf (2003), the main limitation is that this approach is based on reduction of data and we can never be sure ‘how much valid information is lost because it is contained in the within-type differences’ (p. 328). We aimed to limit this by maximizing differences between types but when people are divided categorically into types some variability must be lost.

The general effects observed for the whole group seem valid and reliable. Moreover relationships between types of subjective well-being and types of temperament were present in all four analysed age groups. However links observed for the phlegmatic type were weaker among adults than among adolescents. This calls for further, more developmentally oriented research on specific functions of stimulation processing capacity and stimulation supply for subjective well-being dimensions in various age groups.

Notes

We use the term ‘happy temperament’ to refer to Costa and McCrae’s ‘happy personality’ conception, for sake of continuity between these two labels. However, the well-being operationalization researched here is Diener’s subjective well-being, consisting of positive affect, negative affect and satisfaction with life.

Originally there are six traits, but we discuss only four. The remaining two: sensory sensitivity and perseveration are not vital for determining temperament types. As stated by Zawadzki and Strelau (1997) and by Jankowski and Zajenkowski (2009) to determine the type of temperament that a person represents we must compute stimulation processing capacity (inversed emotional reactivity + endurance scores) and stimulation supply (activity + briskness).

Data on perseveration and sensory sensitivity were also collected, but we do not analyze them in this article.

We use the term negative affective balance to indicate a less favorable affective balance in comparison to the mean calculated for all subjects. This, however, does not mean that the negative affect was more intense than positive affect. In our group this was rarely the case—see Table 1 for mean results.

References

Asendorpf, J. B. (2003). Head‐to‐head comparison of the predictive validity of personality types and dimensions. European Journal of Personality, 17(5), 327–346. doi:10.1002/per.492.

Asendorpf, J. B., Borkenau, P., Ostendorf, F., & Van Aken, M. A. (2001). Carving personality description at its joints: Confirmation of three replicable personality prototypes for both children and adults. European Journal of Personality, 15(3), 169–198.

Avsec, A., Kavčič, T., & Jarden, A. (2015). Synergistic paths to happiness: Findings from seven countries. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(4), 1371–1390.

Bartels, M., & Boomsma, D. I. (2009). Born to be happy? The etiology of subjective well-being. Behavior Genetics, 39(6), 605–615. doi:10.1007/s10519-009-9294-8.

Bojanowska, A., & Zalewska, A. M. (2011). Subjective well-being among teenagers of different ages: The role of emotional reactivity and social support from various sources. StudiaPsychologiczne, 49(5), 5–21. doi:10.2478/v10167-010-0037-5.

Bojanowska, A., & Zalewska, A. M. (2015). Lay understanding of happiness and the experience of well-being—Are some conceptions of happiness more beneficial than others? Journal of Happiness Studies,. doi:10.1007/s10902-015-9620-1.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Bennett, E., & Furnham, A. (2007). The happy personality: Mediational role of trait emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(8), 1633–1639. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.10.029.

Cieslak, R., Korczynska, J., Strelau, J., & Kaczmarek, M. (2008). Burnout predictors among prison officers: The moderating effect of temperamental endurance. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(7), 666–672. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.07.012.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1980). Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being: Happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 668–678. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.38.4.668.

DeNeve, K. M., & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 124(2), 197–229. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.197.

de Pascalis, V., Jeger, K., Chiaradia, C., & Carotenuto, E. (2003). Ból, temperament i różnice indywidualne w aktywności autonomicznej. In M. Marszał-Wiśniewska, T. Klonowicz, & I. M. Fajkowska-Stanik (Eds.), Psychologia różnic indywidualnych. Wybrane zagadnienia (pp. 58–70). Gdansk: GWP.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34–43. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34.

Diener, E., & Diener, C. (1996). Most people are happy. Psychological Science, 7(3), 181–185. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1996.tb00354.x.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13.

Fruehstorfer, D. B., Veronie, L., Cremeans-Smith, J. K., & Newberry, B. H. (2012). Predicting illness-related outcomes with FCB-TI trait pairs: Examining the nonadditive effects of FCB-TI perseveration. Journal Of Individual Differences, 33(4), 248–256. doi:10.1027/1614-0001/a000070.

Garcia, D., & Moradi, S. (2013). The affective temperaments and well-being: Swedish and Iranian adolescents’ life satisfaction and psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(2), 689–707. doi:10.1007/s10902-012-9349-z.

Heszen, I. (2012). Temperament and coping activity under stress of changing intensity over time. European Psychologist, 17(4), 326–336. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000121.

IBM Corp. (2011). IBM statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Jankowski, K. S., & Zajenkowski, M. (2009). Ilościowe metody szacowania struktury temperamentu w ujęciu regulacyjnej teorii temperamentu [Quantitative methods of estimating temperament structure according to regulative theory of temperament]. Psychologia Etologia Genetyka, 19, 55–70.

Jankowski, K. S., & Zajenkowski, M. (2012). Mood as a result of temperament profile: Predictions from the regulative theory of temperament. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(4), 559–562. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.012.

Kandler, C., Held, L., Kroll, C., Bergeler, A., Riemann, R., & Angleitner, A. (2012). Genetic links between temperamental traits of the regulative theory of temperament and the big five: A multitrait-multimethod twin study. Journal of Individual Differences, 33(4), 197–204. doi:10.1027/1614-0001/a000068.

Kandler, C., Riemann, R., & Angleitner, A. (2013). Patterns and sources of continuity and change of energetic and temporal aspects of temperament in adulthood: A longitudinal twin study of self- and peer reports. Developmental Psychology, 49(9), 1739–1753. doi:10.1037/a0030744.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43, 207–222.

Klonowicz, T. (2001). Discontented people: Reactivity and locus of control as determinants of subjective well-being. European Journal of Personality, 15(1), 29–47. doi:10.1002/per.387.

Lucas, R. E., Diener, E., & Suh, E. (1996). Discriminant validity of well-being measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(3), 616–628. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.71.3.616.

McCrae, R. R., Costa, P. T, Jr., Ostendorf, F., Angleitner, A., Hřebíčková, M., Avia, M. D., et al. (2000). Nature over nurture: temperament, personality, and life span development. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(1), 173.

McKennell, A. (1978). Cognition and affect in perceptions of well-being. Social Indicators Research, 5(4), 389–426.

Rothbart, M. (1981). Measurement of temperament in infancy. Child Development, 52, 569–578.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081.

Rzeszutek, M., & Schier, K. (2014). Temperament traits, social support, and burnout symptoms in a sample of therapists. Psychotherapy, 51(4), 574–579. doi:10.1037/a0036020.

Scholte, R. J., van Lieshout, C. M., de Wit, C. M., & van Aken, M. G. (2005). Adolescent personality types and subtypes and their psychosocial adjustment. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 51(3), 258–286.

Shmotkin, D., Berkovich, M., & Cohen, K. (2006). Combining happines’s and suffering in a retrospective view of anchor periods in life: A differential approach to subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 77(1), 139–169. doi:10.1007/s11205-005-5556-x.

Strelau, J. (2008). Temperament as a regulator of behaviour: After 50 years of research. Clinton Corners, New York: Eliot Werner Publications.

Strelau, J., & Zawadzki, B. (1995). The formal characteristics of behaviour—temperament inventory (FCB—TI): Validity studies. European Journal of Personality, 9, 207–229. doi:10.1002/per.2410090304.

Tellegen, A., Lykken, D. T., Bouchard, T. J., Wilcox, K. J., Segal, N. L., & Rich, S. (1988). Personality similarity in twins reared apart and together. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1031–1039. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1031.

Thomas, A., & Chess, S. (1977). Temperament and development. Oxford: Brunner/Mazel.

Torras, M. (2008). The subjectivity inherent in objective measures of well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(4), 475–487.

Trzebińska, E. (2008). Psychologia pozytywna. Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Akademickie i Profesjonalne.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070. doi:10.1177/1073191108328890.

Wytykowska, A. (2012). The type of temperament, mood, and strategies of categorization. Journal of Individual Differences, 33(4), 227–236. doi:10.1027/1614-0001/a000073.

Zalewska, A. M. (2003). Dwaświaty [Two worlds]. Warszawa: Academica.

Zalewska, A. M. (2004). Transactional model of subjective well-being. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 35, 45–53. Poland: Blackhorse Publishing.

Zalewska, A. M. (2011). Relationships between anxiety and job Satisfaction—three approaches: ‘bottom–up’, ‘top–down’, and ‘transactional’. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 977–986. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.10.013.

Zawadzki, B., & Popiel, A. (2012). Temperamental traits and severity of PTSD symptoms: Data from longitudinal studies of motor vehicle accident survivors. Journal of Individual Differences, 33(4), 257–267. doi:10.1027/1614-0001/a000074.

Zawadzki, B., & Strelau, J. (1997). Formalna Charakterystyka Zachowania—Kwestionariusz Temperamentu. Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych PTP: Podręcznik. Warszawa.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bojanowska, A., Zalewska, A.M. Happy Temperament? Four Types of Stimulation Control Linked to Four Types of Subjective Well-Being. J Happiness Stud 18, 1403–1423 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9777-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9777-2