Abstract

Research consistently shows an association between marriage and divorce and long-term health, including mental health outcomes linked to loneliness and depression. And, recent evidence suggests that divorce at midlife and older, or so-called “gray divorce” has increased while divorce at younger ages has decreased. Using data from the Netherlands Kinship Panel Study (NKPS), this chapter explores the association between marital status and social and emotional loneliness, emphasizing gray divorce. Contrary to expectations, compared to those continuously married (e.g., never divorced), gray divorce is not associated significantly with social loneliness, but divorce prior to midlife is. On the other hand, those who divorced prior to and after midlife were emotionally lonelier than those continuously married, regardless of birth cohort and remarriage. In addition, compared to their married counterparts of the same age, there was no association between divorce and social loneliness for women, but there was for men who divorced both before and after midlife. Among only the divorced group, gray divorce (versus younger divorce) was not associated significantly with social nor emotional loneliness for women or men. Also among only those who divorced, gray divorced men (versus younger divorced men) were less emotionally lonely, but this finding was not statistically significant.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Divorce in Western countries has increased substantially over the past half century and remains at or above 30% of all marriages ending in divorce, including in the Netherlands. Recent research in the United States, however, suggests that there have been significant within-group changes in divorce. That is, the risk of divorce among young, teenage couples has decreased significantly. On the other hand, the risk of divorce among older couples increased. The (U.S.) divorce rate among adults age 50 or older doubled between 1990 and 2010, and 25% of all divorces were among those age 50 and older (Brown and Lin 2012; Kennedy and Ruggles 2014). No similar reports (to the author’s knowledge) have been published for The Netherlands; figures from Statistics Netherlands (author’s calculations, not shown) suggest that divorces among those age 50 and older have increased since the latter part of the twentieth and earlier part of the twenty-first centuries. While there are a few studies examining the consequences of divorce at older ages, overall, the consequences of gray divorce are not well-understood.

Research consistently shows that there are benefits to marriage, both in terms of long-term physical health and long-term mental health, especially for men (e.g., Waite and Gallagher 2002). The potential social and emotional (negative) consequences of being a divorcee versus married may differ on a number of characteristics, including the age of divorcees and whether they subsequently remarry. Indeed, those who divorce earlier rather than later in the life course may be more likely to remarry or cohabit with a new partner (see Lewis and Kreider 2015). They may also have more opportunities to rebuild their social lives with new partners, and thus be less likely to suffer from loneliness. Divorce later in life, or what is often referred to as “gray divorce,” may place older adults at a greater risk of loneliness compared to those who are married, regardless of first or higher order marriages. On the other hand, similar to younger divorcees, those who end marriages at midlife and later may do so for reasons that improve their quality of life and reduce the chances of loneliness.

Few studies have considered the potential social and emotional consequences of divorce across different age groups; literature exploring gray divorce is limited, and these studies often do not include younger divorcees (prior to midlife) (see Brown and Lin 2012). This chapter extends the literature by using data from the Netherlands Kinship Panel Study to explore the association between divorce both before and after age 50 (consistent with Brown and Lin 2012) and social and emotional loneliness. Specifically, omissions in the extant literature are addressed by exploring the following primary research questions. To what extent does the association between divorce and loneliness differ for younger and older divorcees compared to one-time, continuous marriages? Do remarriages among different age groups protect against social and emotional loneliness? To what extent does health and employment attenuate the association between divorce and loneliness?

2 Background

2.1 Loneliness

Scholars have long been interested in loneliness, both as a predictor of health and as an outcome of the quantity and quality of social relationships (e.g., see Cohen-Mansfield et al. 2016). Over many years, numerous theories of loneliness have been posited, followed by hundreds of empirical studies seeking to understand the causes and consequences of loneliness. Distinct from the concept of social isolation (i.e., an absence of social relationships), loneliness is defined as “…a situation experienced by the individual as one where there is an unpleasant or inadmissible lack of (quality of) certain relationships. This includes situations, in which the number of existing relationships is smaller than is considered desirable or admissible… [and] the intimacy one wishes for has not been realized” (de Jong Gierveld 1987: 120; de Jong Gierveld et al. 2006). Thus, loneliness is the feeling that the social relationships in one’s life are either lacking, undesirable, unfulfilling, or they do not meet one’s expectations of quality.

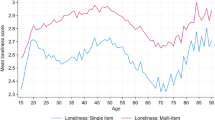

To capture the more distinct dimensions of loneliness, Weiss (1973) posited that the characteristics of one’s social relationships determine the extent to which two distinct types of loneliness, social and emotional, emerge. Social loneliness may result from a mismatch between one’s expectations of—or personal standards for—the quality of their ties and the composition and/or size of their personal network. Similarly, emotional loneliness may result when the intimacy one expects from their social relationships is lacking (see de Jong Gierveld 1987 and de Jong Gierveld 1998 for more discussion). Thus, while similar in terms of unmet expectations, social and emotional loneliness capture two distinct unmet needs—social has to do with ties to others and emotional loneliness has to do with intimacy. Intuitively, the extent to which one feels social and/or emotional loneliness is likely associated strongly with the strength of intimate partner relationships (e.g., Weiss 1973; Dykstra and de Jong Gierveld 2004). In terms of social and emotional loneliness following divorce, on average, we would expect both to increase; however, the patterns may differ for women and men as women tend to seek emotional intimacy elsewhere in their supportive networks (e.g., Dykstra and de Jong Gierveld 2004).

2.2 Divorce and Loneliness

Regardless of relationship quality, an intimate partner is lost following divorce. While an intimate partner may be the most important social loss, divorce also can result in a loss of shared relationships (e.g., Gerstel 1987), particularly among those married for many years. On the one hand, married couples tend to invest heavily in their couple relationships, and these investments may come at the expense of time with other network members (Kalmijn 2003). Even so, couples may be fulfilled by the social engagement accompanying their marriage, for example, more time with extended family or friendships shared between spouses. The formation of these new couple-centered social networks (Kalmijn and Broese van Groenou 2005) potentially reduces the risk of social loneliness. Moreover, if couple-centered networks include close friendships or relationships with in-laws, these bonds may also reduce the risk of emotional loneliness. On the other hand, if one neglects their individual friends and family to invest in in-laws or otherwise newly formed couple-centered networks, they may be at risk of social and emotional loneliness if they long for time with old friends and immediate family. In these cases, social loneliness may be prevalent among those who have been married for many years (e.g., Dykstra and de Jong Gierveld 2004). Indeed, some research suggests that low quality of marriages in later life (between ages 64 and 92), in terms of social and emotional support (among other indicators), are associated with both social and emotional loneliness (de Jong Gierveld et al. 2009).

It is possible that the dissolution of low-quality intimate partnerships or marriages later in life results in not only a sense of relief, but also an increase in time with family or possibly even friends (e.g., Gerstel 1988; Albeck and Kaydar 2002; Kalmijn and Broese van Groenou 2005). Even so, research primarily shows that older versus younger adults are more likely to be socially isolated (Steptoe et al. 2013), suggesting that older adults may be more vulnerable to social loneliness if they would prefer to have more social contact. Although, it is also possible that older divorcees spend more time with their adult children and grandchildren, and thus suffer less from social and emotional loneliness. Indeed, research suggests that grandparent involvement in families has increased over time, and in many cases, grandparents coreside with their adult children and their families (e.g., Dunifon et al. 2014).

Even so, some research suggests that older adults who have ever divorced are socially and emotionally lonely compared to those who have had no changes in their marital history (i.e., in first marriage and never married), although the patterns differ for women and men (Dykstra and de Jong Gierveld 2004). It is possible that adult children are less readily available socially and emotionally outside of time shared with young children. Moreover, older adults may have less energy for social activities following a later in life divorce, particularly if they have health problems. Some evidence suggests that, health problems notwithstanding, participation in social activities and the formation of new relationships can be very difficult following a divorce (Kalmijn and Broese van Groenou 2005), so adults with health problems often face even greater social challenges (e.g., Steptoe et al. 2013).

Using longitudinal data from the late 1980s, Terhell et al. (2004) found that 50% of men and women lost friendships in divorces, which were subsequently not replaced 12 years later (Terhell et al. 2004). Some participants gained friendships several years after their divorce, which suggests that some friendships that are lost in a divorce require time to regain or replace, whereas others are not replaced. Thus, the potential protection against social loneliness that friendship networks afford may take time. Conceivably, such a time lag results in divorcees feeling both emotionally and socially lonely. This may be particularly true if older divorcees had shared contacts with their spouses. There is some evidence of this among older, divorced men who do not remarry or repartner (Gray et al. 2011).

While no studies (of which the author is aware) have examined explicitly the patterns of social and emotional loneliness among divorcees prior to midlife, intuitively, those who divorce earlier rather than later in the life course may be more likely to re-partner following a divorce (e.g., Cohen-Mansfield et al. 2016). Thus, younger divorcees may have a lower risk of social and emotional loneliness. Indeed, older divorcees may be less likely to remarry strictly due to the pool of single adults, as many in this age group will already be married (or remarried). Among older adults who do remarry, such new intimate partnerships may bring with them emotional and social fulfillment (e.g., Gray et al. 2011), particularly if adult children are amiable toward the new partnerships. On the other hand, those who divorce and remarry earlier in life (e.g., prior to midlife) may experience less emotional loneliness than their married counterparts, especially if they left an emotionally unfulfilling marriage (e.g., Amato and Hohmann-Marriott 2007). On the other hand, research suggests that couples who remarry suffer from stress (e.g., Sweeney 2010) that could place young children at risk of negative outcomes, such as performing poorly in school. Conflict associated with divorce and shared responsibility for children across households, along with the subsequent stress of navigating a new life with children from the older one, may mean that younger divorced and remarried adults feel socially lonelier than those who stay in their first marriages.

2.3 Gender Differences

Prior research suggests that there are notable differences in how intimate romantic partnerships affect the social and emotional lives of women and men. Overall, men and women benefit from marriage both in terms of health outcomes and financially (Waite and Gallagher 2002; Robles et al. 2014). Men also tend to benefit emotionally from marriage, but emotional security for women comes from other social ties (Dykstra and de Jong Gierveld 2004). Married women tend to invest more in social ties and keep closer social relationships with kin (e.g., Rosenthal 1985). Thus, when marriages dissolve, we might expect the divorce to increase emotional loneliness for men as they rely on their marriages as a primary source of this support. On the other hand, women may suffer less emotionally post-divorce if they draw on supportive networks external to their marriages. However, women who cultivate strong ties with their spouse’s family, and lose those connections post-divorce, may be vulnerable to social loneliness.

Overall, compared to those who are continuously married, I expect divorcees and those in remarriages to have higher levels of social and emotional loneliness. I further expect the association to be stronger for divorcees age 50 and older. While knowledge about gray divorce is currently limited (but growing), the risk of social isolation and loneliness increases with age (e.g., Steptoe et al. 2013). Thus, given the overall increased risk of loneliness, combined with a potential loss of support from spouses and/or their families following divorce, I expect that older divorcees may be particularly vulnerable socially. I further expect the association between gray divorce and emotional loneliness to be stronger for men than for women. Men in marriages tend to rely on women for emotional support, and thus may lose a primary source of it following divorce. Conversely, women tend to rely on other family members or friends, rather than their spouses, for emotional support and may experience lower levels of emotional loneliness following a divorce (e.g., Dykstra and de Jong Gierveld 2004). On the other hand, emotion loneliness may increase following divorce if supportive ties are lost in the divorce.

3 Methodology

3.1 Data

This chapter uses data from The Netherlands Kinship Panel Study (NKPS) to explore the extent to which divorce and remarriage among different age groups (versus marriage) is associated with social and emotional loneliness. Part of the Generations and Gender Programme, the NKPS is a prospective, longitudinal study of N = 9500 individuals and their family members followed across 4 waves between 2000–2004 (Wave 1) and 2014 (Wave 4). This panel study is a collaboration between several Dutch universities and has been funded primarily by the Dutch National Research Foundation (NWO). The purpose of the study was to better understand solidarity in family relationships and family behavior over time. Data were collected using face-to-face interviews, which included both closed- and open-ended questions.

Data from the NKPS are suitable for the current study because they include measures about divorce, age of divorce, the De Jong Gierveld scales of social and emotional loneliness, and demographic characteristics. Attrition in Waves 3 and 4, however, was substantial. Thus, to avoid potentially biased estimates from high levels of attrition, and to retain a larger proportion of the sample in the analyses, this study used information from Waves 1 and 2 of the NKPS. Data were pooled over the two waves, and robust standard errors were used to adjust for multiple individual observations at two time points. In addition, to further retain more individuals in the sample, item missing (less than 30% for any given item) for covariates only were multiply imputed using the ICE command in Stata. Missing values were not imputed for marital status nor social and emotional loneliness. Finally, because the focus of the paper was divorce before and after midlife, the never married and widows/widowers were excluded. The resulting analytic sample size was N = 8505 observations.

3.2 Independent Variables

Two primary independent variables were included in the analyses. First, drawing from information about age, divorces, and marital status, a constructed categorical variable of marital status which distinguishes between older and younger divorces and remarriages was included; where 1 = continuously married; 2 = remarried ≥ age 50; 3 = remarried < age 50; 4 = divorced ≥ age 50; 5 = divorced < age 50. Importantly, those in the continuously married category have only ever been married or a registered cohabiting partner with their current partner; and those in both divorced categories had not remarried since their divorce. In analyses restricted to only those who have divorced, a dummy indicator is used, where 1 = divorced ≥ age 50; 0 = divorced < age 50.

3.3 Dependent Variables

Two dependent variables were included in the analyses, one of which captured social loneliness and the other captured emotional loneliness. These measures were adapted in the NKPS from De Jong Gierveld and Kamphuis (1985) loneliness scale. To capture loneliness, NKPS participants were given a series of 11 items about their social and emotional lives and were asked to rank them (i.e., 1 = yes; 2 = more or less; 3 = no). The items were (1) always someone to talk to about day to day problems; (2) missing having a really close friend; (3) experience a general sense of emptiness; (4) plenty of people I can lean on; (5) miss the pleasure of the company of others; (6) my circle of friends and acquaintances too limited; (7) there are many people I can trust completely; (8) there are enough people I feel close to; (9) missing having people around; (10) often feel rejected; (11) I can call on my friends whenever I need them.

Consistent with prior research (e.g., Dykstra and de Jong Gierveld 2004), including studies suggesting that the separate dimensions of the loneliness scale—social and emotional—are valid and reliable (e.g., de Jong Gierveld and van Tilburg 2010), items 1, 4, 7, 8, and 11 constitute the social loneliness score (Cronbach’s alpha reliability score = .80) and items 2, 3, 5, 6, 9, and 10 constitute the emotional loneliness score (Cronbach’s alpha reliability score = .82). The procedure for using the scales required several steps (see de Jong Gierveld and van Tilburg 1999). For both the social and emotional loneliness scales, the first step was to reverse-code positive responses (e.g., there are enough people I feel close to) such that 1 indicated a positive response and 3 indicated a negative. Next, each item was recoded into dummy variables indicating a negative response (i.e., yes and more or less = 1; and no = 0). Next, dummy variables for each dimension were summed, resulting in two count measures. Social loneliness ranged from 0 to 5, where 0 represented no social loneliness and 5 represented high levels of social loneliness. Similarly, emotional loneliness ranged from 0 to 6, where 0 represented no emotional loneliness and 6 represented high levels of emotional loneliness.

3.3.1 Covariates

Several covariates were included in the analyses to rule out potential factors that may confound the association between divorce and loneliness; and to determine whether the association between divorce and loneliness may be explained by additional factors. First, given that prior research strongly suggests the importance of socioeconomic status in both marital status outcomes (e.g., McLanahan 2004) and mental health related issues (e.g., Reiss 2013), models adjust for respondents’ educational attainment and income. Similarly, demographic characteristics including age, sex, immigrant status, and birth cohort were controlled. Age was measured in years. Sex and immigrant status were dummy indicators where 1 = female and 0 = male; and for immigrant status, 1 = born outside of the Netherlands and 0 = born in the Netherlands. Birth cohort was measured using dummy indicators for 10-year birth intervals (i.e., 1920s through the 1980s). Education was measured using four dummy indicators for primary, lower secondary, upper secondary, and tertiary education. Income was measured in Euros and divided into quintile dummy indicators (reference = first quintile). Models also adjust for the duration of marriage (in years), as it may be associated with the risk of divorce and social and emotional loneliness. This covariate adjusted for number of years of only marriage or current marriage among the married and remarried groups, and years of the last marriage among the divorced groups. A dummy indicator also was included for whether the divorce occurred within the past 3 years. In addition, because the presence of children may be an important determinant of marital status, age of divorce, and whether or not one is socially or emotionally lonely, dummy indicators were included for number of children and whether or not children lived at home. Finally, self-reported health ranging from 1 = poor to 5 = excellent and whether or not respondents were employed for pay were added as potential mediators. Table 7.1 shows descriptive statistics for all variables included in the analyses.

4 Analytic Approach

The analysis begins with a description of the sample (presented in Table 7.1). Second, four multivariate models were estimated for each outcome, social and emotional loneliness (presented in Tables 7.2 and 7.3). These models included the total analytic sample—all marital statuses were included for the purposes of comparison, and taking into account whether participants were divorced before or after age 50. The first model included marital status, socioeconomic background, demographic characteristics, duration of marriage, years since divorce. Model 2 added information about children as they may buffer against loneliness, particularly as parents age. Model 3 adds paid employment to Model 2—employed people may be less likely to feel loneliness due to time spent with co-workers. Model 4 added self-reported health because healthier people may be better able to engage socially compared to those who are less healthy, and health likely differs between younger and older divorcees. Third, separate models were estimated for each cohort to determine similarities and differences in the associations between divorce and social and emotional loneliness across birth cohorts. Models were estimated using negative binomial regression (NBR) as the outcomes, social and emotional loneliness, were over-dispersed count data. Over-dispersion means that the conditional variance exceeds the conditional mean, and in this case, Poisson regression would return less precise confidence intervals (Long 1997). Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) from negative binomial regression models with robust standard errors to adjust for nonindependence across waves are reported for all analyses. IRRs offer a more intuitive interpretation than NBR coefficients, which tell us the differences in the log of expected counts. For example, one would interpret an IRR for social loneliness as the factor with which the rate of change in social loneliness occurs when we shift from the married (reference) to the divorced group.

4.1 Results

Table 7.2 shows the results of the four negative binomial regression models estimating social loneliness by marital status and covariates. In Model 1, after adjusting for demographic characteristics, duration of marriage, and whether divorced in last 3 years, compared to those who were continuously married (i.e., no divorce nor remarriage), the only significantly different group was those who were younger than age 50 and divorced. Holding constant all other groups, and controlling for demographic characteristics, duration of marriage, and divorced within last 3 years, the younger divorced group versus those continuously married had a rate 1.20 times greater for social loneliness. While the same was true for all other marital status groups, the IRRs were not significant and all were close to one. The relationship changed very little once additional covariates—for children and individual characteristics—were added in Models 3 and 4. In terms of the covariate associations with social loneliness, after all adjustments in Model 4, the rate was lower for females compared to males by a factor of.76 and those born outside of the Netherlands were significantly socially lonelier (1.36 times greater) than those native born. Moreover, those born in the 1930s (a factor of.84) and the 1950s (a factor of.79) were less socially lonely compared to those born earlier, in the 1920s. It is important to note that the reference category may be a selective group as they were born in the 1920s and still alive, and thus may have had relatively lower levels of loneliness. Still, the significantly lower rate ratio in the 1950s cohort may be due to period effects, and 1950s predating the dramatic rise in divorce in Western countries.

Turning now to Table 7.3, while the patterns of association between those divorced younger than age 50 and emotional loneliness were largely the same, the magnitude of the association was stronger compared to the results for social loneliness. Focusing on Models 3 and 4, holding all else constant, those younger than age 50 versus those who were married were emotionally lonelier by a factor of 1.93. While the size of the IRR was larger for this group, in comparison to those continuously married, both remarried and divorced groups were emotionally lonelier than the continuously married. Moreover, the addition of self-reported health in Model 4, reduces the magnitude of all marital status IRRs; the largest decrease was for those age 50 and older (i.e., IRR decreases from 1.97 to 1.81), and suggests that divorce at or older than age 50 (in part) operates through health to influence emotional loneliness. In terms of covariates, apart from birth cohort (where there were more cohort differences) and sex and whether or not children live at home (where there were no associations), the patterns were the same for emotional loneliness as they were for social loneliness in Table 7.2. It is worth noting that education appears to be protective against both social and emotional loneliness (Tables 7.2 and 7.3), which is consistent with what we would expect given the overall education gradient in health (e.g., Elo and Preston 1996).

Next, the results of three separately estimated negative binomial models for women and men are shown in Table 7.4. The first and second columns restrict the samples to those younger than age 50 and those age 50 and older and predicts social and emotional loneliness by whether women and men were divorced and married (reference category) for their respective age groups, net of all covariates. The third column (for women and men) restricts the sample to only those who were divorced and age 50 and older and those who were divorce and younger than age 50 (reference category). Focusing first on the three models for women, those divorced who were younger than age 50 are more socially and emotionally lonely compared to their married counterparts. However, the magnitude of the association was higher for emotional loneliness. In terms of both social and emotional loneliness, there was no significant difference between older divorced women and their married counterparts, nor was there a difference between older and younger divorced women. In terms of men, on the other hand, the rates of social and emotional loneliness were greater for both younger and older divorced men compared to their married counterparts of the same age. Older versus younger divorced men were less emotionally lonely, although the IRR was not statistically significant. Older and younger divorced men did not differ in terms of social loneliness.

Finally, Cherlin (2010) argues that the meaning of marriage has changed over time, shifting from instrumental institutions that contribute to the wellbeing of societies to more individual, emotional unions characterized by a pursuit of love and happiness. Given this possibility, combined with divorce becoming increasingly normative over time, it is important to consider potential cohort differences in the association between divorce and social and emotional loneliness. Table 7.5 shows the results from NBR models estimated separately by birth cohort, net of all covariates (collapsing categories for 1920s and 1930s and for 1970s and 1980s because these categories were smallest). Among those born in the 1920s through the 1960s, the patterns of association for both social and emotional loneliness were the same. There was no association between being divorce versus married and social loneliness, rather within each of these cohort groups, the divorced were significantly emotionally lonelier compared married groups within the same cohort (by factors ranging from 1.55 for the 1960s cohort to 1.89 for the 1920s and 1930s cohorts). There was no statistically significant association between divorce and social nor emotional loneliness for the 1970s and 1980s cohort group.

5 Discussion

This chapter extends knowledge about the association between marital status, and particularly gray divorce and social and emotional loneliness. First, unlike the few studies that examine the consequences of gray divorce in particular, the current study includes a more recent sample, accounts for divorce prior to and after age 50, examines the association between divorce and loneliness across cohort groups, and explores the role of health and employment in these associations. Contrary to expectations, results from the NKPS (full sample) suggest that gray divorce is not associated significantly with social loneliness, but there does appear to be a significant association between divorce prior to midlife and social loneliness. Both those divorced prior to and after midlife were emotionally lonelier than their married counterparts, regardless of age, birth cohort, and remarriage. While the associations between younger divorce and gray divorce (versus each age group’s respective married counterparts) and emotional loneliness did not differ much for women and men, younger and gray divorced men were socially lonelier than their married counterparts (in their respective age groups). When the sample was restricted to divorcees, there were no significant differences for neither women nor men. Interestingly, gray divorced men were less emotionally lonely compared to their younger divorced counterparts, but the association was not statistically significant. Interestingly, while women versus men were significantly socially lonelier in the full sample (Table 7.2), there was no association between divorce and social loneliness in our separate estimates for women and men (in Table 7.3). Conversely, while there was no difference between women and men in terms of emotional loneliness in our full sample; separately, gray and younger divorce increased significantly emotional loneliness for women by a factor of 1.90 and 1.50 respectively. Finally, in terms of health and employment, health (but not employment) attenuated part of the association between divorce prior to midlife and after and emotional loneliness.

There may be a bi-directional relationship between divorcing later in life and health. Those who are healthier may be in part socially and emotionally protected as they may be better capable of seeking out new friendships or spending time with grandchildren. Healthy older divorcees may invest more in living more socially active lives following a divorce (e.g., Gerstel 1988; Kalmijn and Broese van Groenou 2005), particularly older women. This may be why there was no evidence that neither older divorced versus married women, nor older versus younger divorced women were socially lonelier. On the other hand, those who are either physically or psychologically less healthy may experience both declines in physical and psychological health, and the risk of loneliness. Moreover, our findings suggest that younger and older women versus men may be socially lonelier, but this does not appear to be the result of divorce. It may be that women’s versus men’s personal standards for, or expectations of, the quality or quantity of their social relationships go unmet. The cultivation of kinship ties and seeking of emotional support outside of women’s marriages may strain personal relationships, leaving women feeling more socially than emotionally lonely.

Other findings were consistent with prior research (Dykstra and de Jong Gierveld 2004) in terms of older divorced versus married men, who were both more socially and emotionally lonely. While I expected older divorced men to be emotionally lonelier than younger divorced men, as younger men may have more options to repartner or spend time with friends, it appears that divorced younger men were more vulnerable to emotional loneliness. This may be simply about age. That is, it is possible that younger men have higher expectations for emotional support from a spouse. Whereas, older men may find other sources of emotional support, possibly a benefit of time (e.g., Weiss 1973).

6 Conclusion

There are several limitations to this study. First, as is the case with all observational, longitudinal studies, attrition across study waves may introduce biased estimates. While missing values were multiply imputed for covariates, they were not for marital status nor social and emotional loneliness. It may be that the most disadvantaged groups, or those who move to undisclosed locations and cannot be found for follow-up, are the most likely to attrite from the study. Thus, to the extent that this is true, it is difficult to determine whether these groups are more or less likely to divorce and suffer from social and emotional loneliness. Second, the results of the current study may be biased to the extent that pre- and post-divorce circumstances more strongly predict the likelihood that one is lonely than the actual divorce itself. Given the short time between waves 1 and 2 of the study (approximately 2 years), there were too few marital status changes to examine how pre-divorce circumstances affected post-divorce levels of social and emotional loneliness. This is an important avenue for future research.

There are many challenges associated with studying gray divorce, as the event itself may be due to factors which came long before the observation period. This unobserved heterogeneity is difficult to address as the life course is a long process. Despite the limitations, however, this study contributes to the literature an examination of how divorce and remarriage among different age groups influence two important dimensions of loneliness, and offers some potential avenues for future research. The proportion of couples who divorce at or later than midlife may continue to grow, and scholars should continue to investigate loneliness and other dimensions of social life that may have long-term consequences for health and longevity (e.g., Holt-Lunstad et al. 2015).

References

Albeck, S., & Kaydar, D. (2002). Divorced mothers: Their network of friends pre- and post-divorce. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 36, 111–138.

Amato, P. R., & Hohmann-Marriott, B. (2007). A comparison of high- and low-distress marriages that end in divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(3), 621–638.

Brown, S. L., & Lin, I.-F. (2012). The gray divorce revolution: Rising divorce among middle-aged and older adults, 1990–2010. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67(6), 731–741.

Cherlin, A. (2010). Marriage-go-round: The state of marriage and the family in America today. New York: Vintage Books.

Cohen-Mansfield, J., Hazan, H., Lerman, Y., & Shalom, V. (2016). Correlates and predictors of loneliness in older-adults: A review of quantitative results informed by qualitative insights. International Psychogeriatrics, 28(4), 557–576.

de Jong Gierveld, J. (1987). Developing and testing a model of loneliness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 119–128.

de Jong Gierveld, J., & Kamphuis, F. (1985). The development of a rasch-type loneliness scale. Applied Psychological Measurement, 9, 289–299.

de Jong Gierveld, J., & van Tilburg, T. G. (1999). Manual of the loneliness scale. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Department of Social Research Methodology.

de Jong Gierveld, J., & van Tilburg, T. (2010). The De Jong Gierveld short scalles for emotional and social loneliness: Tested on data from 7 countries in the UN Generations and Gender Surveys. European Journal of Ageing, 7, 121–130.

de Jong Gierveld, J., van Tilburg, T., & Dykstra, P. A. (2006). Loneliness and social isolation. In D. Perlman & A. Vangelisti (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships (pp. 485–500). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

de Jong Gierveld, J., van Groenous, M. B., Hoogendoorn, A. W., & Smit, J. H. (2009). Quality of marriages in later life and emotional and social loneliness. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 64(4), 497–506.

Dunifon, R. E., Ziol-Guest, K. M., & Kopko, K. (2014). Grandparent coresidence and family well-being: Implications for research and policy. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654, 110–126.

Dykstra, P. A., & de Jong Gierveld, J. (2004). Gender and marital-history differences in emotional and social loneliness among Dutch older adults. Canadian Journal on Aging, 23(2), 141–155.

Elo, I., & Preston, S. H. (1996). Educational differentials in mortality: United States, 1979–1985. Social Science and Medicine, 42(1), 47–57.

Gerstel, N. (1987). Divorce and stigma. Social Problems, 34, 172–186.

Gerstel, N. (1988). Divorce, gender, and social integration. Gender and Society, 2(3), 343–367.

Gray, M., De Vaus, D., Qu, L., & Stanton, D. (2011). Divorce and the wellbeing of older Australians. Ageing and Society, 31, 475–498.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237.

Kalmijn, M. (2003). Friendship networks over the life course: A test of the dyadic withdrawal hypothesis using survey data on couples. Social Networks, 25, 231–249.

Kalmijn, M., & Broese van Groenou, M. (2005). Differential effects of divorce on social integration. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22, 455–476.

Kennedy, S., & Ruggles, S. (2014). Breaking up is hard to count: The rise of divorce in the United States. Demography, 51, 587–598.

Lewis, J. M., & Kreider, R. M. (2015). Remarriage in the United States. American Community Survey Reports ACS, 30, 1–12.

Long, J. S. (1997). Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

McLanahan, S. (2004). Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography, 41(4), 607–627.

Reiss, F. (2013). Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Social Science and Medicine, 90, 24–31.

Robles, T. F., Slatcher, R. B., Trombello, J. M., & McGinn, M. M. (2014). Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 140.

Rosenthal, C. J. (1985). Kinkeeping in the familial division of labor. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 47(4), 965.

Steptoe, A., Shankar, A., Demakakos, P., & Wardle, J. (2013). Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(15), 5797–5801.

Sweeney, M. M. (2010). Remarriage and stepfamilies: Strategic sites for family scholarship in the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 667–684.

Terhell, E. L., Broese van Groenou, M. I., & van Tilburg, T. (2004). Network dynamics in the long-term period after divorce. Journal of Personal and Social Relationships, 21, 719–738.

Waite, L. J., & Gallagher, M. (2002). The case for marriage: Why married people are happier, healthier, and better off financially. New York: Doubleday.

Weiss, R. S. (1973). Loneliness: The experiences of emotional and social isolation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Acknowledgement

This chapter benefited from the support of the Centre for Population, Family and Health (CPFH) at the University of Antwerp and the Flemish Agency of Innovation and Entrepreneurship (Grant number:140069), which enabled Open Access to this chapter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Högnäs, R.S. (2020). Gray Divorce and Social and Emotional Loneliness. In: Mortelmans, D. (eds) Divorce in Europe. European Studies of Population, vol 21. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25838-2_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25838-2_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-25837-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-25838-2

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)