Abstract

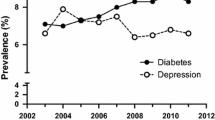

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is often a chronic, recurrent, and debilitating health problem with a lifetime prevalence of 16.2% and a 12-month prevalence of 6.6% in the USA [1]. Left untreated, depression can have a significant negative impact on a person’s social, physical, and mental well-being and place an enormous burden on society. Patients with depression experience a higher incidence of premature death related to cardiovascular disease [2, 3] and are 4.5 times more likely to suffer a myocardial infarction than those without depression [3]. Depression in patients with diabetes is associated with increasing rates of vascular complications and increased mortality [4]. In terms of economic burden, the total cost of depression in the USA was estimated at $83.1 billion in 2000 [5]. Major contributors to depression-related cost were lost productivity and direct medical expenses, which accounted for $30–$50 billion each year [6]. Compared with nondepressed patients, health service costs for depressed patients are 50–100% greater, mainly due to higher overall medical utilization [7, 8].

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Trivedi MH, Lin EH, Katon WJ. Adherence with antidepressant therapy and successful patient self-management. CNS Spectr. 2007;12(8 Suppl 13):1–27.

Musselman DL, Evans DL, Nemeroff CB. The relationship of depression to cardiovascular disease: epidemiology, biology, and treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:558, 580–592.

Pratt LA, Ford DE, Crum RM, et al. Depression, psychotropic medication, and risk of myocardial infarction. Prospective data from the Baltimore ECA follow-up. Circulation. 1996;94:3123–3129.

Black SA, Markides KS, Ray LA. Depression predicts increased incidence of adverse health outcomes in older Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diab Care. 2003;26:2822–2828.

Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, et al. The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000? J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1465–1475.

Rice DP, Miller LS. Health economics and cost implications of anxiety and other mental disorders in the United States. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1998;172(suppl 34):4–9.

Simon GE, VonKorff M. Recognition, management, and outcomes of depression in primary care. ArchFam Med. 1995;4:99–105.

Henk HJ, Katzelnick DJ, Kobak KA, et al. Medical costs attributed to depression among patients with a history of high medical expenses in a health maintenance organization. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:899–904.

Coyne JC, Fechner-Bates S, Schwenk TL. Prevalence, nature, and comorbidity of depressive disorders in primary care. Gen Hospital Psychiatry. 1994;16:267–276.

Alexander JL, Richardson G, Grypma L, et al. Collaborative depression care, screening, diagnosis and specificity of depression treatments in the primary care setting. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7:S59–80.

Katon W, Sullivan M, Walker E. Medical symptoms without identified pathology: relationship to psychiatric disorders, childhood and adult trauma, and personality traits. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:917–925.

Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diab Care. 2004;27:2154–2160.

Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE, et al. The relationship of depressive symptoms to symptom reporting, self-care and glucose control in diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25:246–252.

Goldman LS, Nielsen NH, Champion HC. Awareness, diagnosis, and treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:569–580.

Hirschfeld RM, Keller MB, Panico S, et al. The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. J Am Med Assoc. 1997;277:333–340.

Judd LL, Paulus MP, Wells KB, et al. Socioeconomic burden of subsyndromal depressive symptoms and major depression in a sample of the general population. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1411–1417.

Coulehan JL, Schulberg HC, Block MR, et al. Treating depressed primary care patients improves their physical, mental, and social functioning. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1113–1120.

Rost K, Smith JL, Dickinson M. The effect of improving primary care depression management on employee absenteeism and productivity. A randomized trial. Med Care. 2004;42:1202–1210.

Demyttenaere K, Mesters P, Boulanger B, et al. Adherence to treatment regimen in depressed patients treated with amitriptyline or fluoxetine. J Affect Disord. 2001;65:243–252.

Demyttenaere K, Enzlin P, Dewe W, et al. Compliance with antidepressants in a primary care setting, 1: beyond lack of efficacy and adverse events. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 22):30–33.

Thompson C, Peveler RC, Stephenson D, et al. Adherence with antidepressant medication in the treatment of major depressive disorder in primary care: a randomized comparison of fluoxetine and a tricyclic antidepressant. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:338–343.

Warden D, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Predictors of attrition during initial (citalopram) treatment for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1189–1197.

Olfson M, Marcus SC, Tedeschi M, et al. Continuity of antidepressant treatment for adults with depression in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:101–108.

Kobak KA, Taylor L, Katzelnick DJ, et al. Antidepressant medication management and Health Plan Employer Data Information Set (HEDIS) criteria: reasons for nonadherence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:727–732.

DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2101–2107.

Katon WJ, Rutter C, Simon G, et al. The association of comorbid depression with mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diab Care. 2005;28:2668–2672.

Akerblad A, Bengtsson F, von Knorring L, et al. Response, remission and relapse in relation to adherence in primary care treatment of depression: A 2-year outcome study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol Bull. 2006;21:117–124.

Peveler R, George C, Kinmonth AL, et al. Effect of antidepressant drug counselling and information leaflets on adherence to drug treatment in primary care: randomised controlled trial. Br Med J. 1999;319:612–615.

Melfi CA, Chawla AJ, Croghan TW, et al. The effects of adherence to antidepressant treatment guidelines on relapse and recurrence of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:1128–1132.

Thase ME, Nierenberg AA, Keller MB, et al. Efficacy of mirtazapine for prevention of depressive relapse: a placebocontrolled double-blind trial of recently remitted high-risk patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:782–788.

Lester H, Howe A. Depression in primary care: three key challenges. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84:545–548.

Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, et al. The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Med Care. 2003;41:479–489.

Schraufnagel TJ, Wagner AW, Miranda J, et al. Treating minority patients with depression and anxiety: what does the evidence tell us? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:27–36.

Melartin TK, Rytsala HJ, Leskela US, et al. Continuity is the main challenge in treating major depressive disorder in psychiatric care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:220–227.

Russell J, Kazantzis N. Medication beliefs and adherence to antidepressants in primary care. New Zeal Med J 2008;121:14–20.

Halfin A. Depression: the benefits of early and appropriate treatment. Am J Manage Care. 2007;13 (4 Suppl):S92–S97.

Bogner HR, Morales KH, Post EP, et al. Diabetes, depression, and death: a randomized controlled trial of a depression treatment program for older adults based in primary care (PROSPECT). Diab Care. 2007;30:3005–3010.

Carnethon MR, Biggs ML, Barzilay JI, et al. Longitudinal association between depressive symptoms and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus in older adults: the cardiovascular health study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:802–807.

Katon W, Fan MY, Unutzer J, et al. Depression and diabetes: a potentially lethal combination. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1571–1575.

Bull SA, Hu XH, Hunkeler EM, et al. Discontinuation of use and switching of antidepressants: influence of patient-physician communication. JAMA. 2002;288:1403–1409.

Peplau H. Interpersonal relations in nursing. New York, NY: Putnam; 1952.

Guadagnino C. Practicing patient-centered collaborative care (Physician News website), 2006.

Lin EH, Von Korff M, Katon W, et al. The role of the primary care physician in patients' adherence to antidepressant therapy. Med Care. 1995;33:67–74.

Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–2845.

Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2428–2429.

Katon W, Rutter C, Ludman EJ, et al. A randomized trial of relapse prevention of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:241–247.

Katon WJ, Seelig M. Population-based care of depression: team care approaches to improving outcomes. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50:459–467.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613.

Ludman E, Katon W, Bush T, et al. Behavioural factors associated with symptom outcomes in a primary care-based depression prevention intervention trial. Psycholog Med. 2003;33:1061–1070.

Hepner KA, Rowe M, Rost K, et al. The effect of adherence to practice guidelines on depression outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:320–329.

Cheung AH, Zuckerbrot RA, Jensen PS, et al. Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): II. Treatment and ongoing management. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1313–e1326.

Schulberg HC, Katon W, Simon GE, et al. Treating major depression in primary care practice: an update of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Practice Guidelines. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:1121–1127.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ Primary Care Study. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744.

Dobscha SK, Gerrity MS, Corson K, et al. Measuring adherence to depression treatment guidelines in a VA primary care clinic. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25:230–237.

Nease DE, Jr., Nutting PA, Dickinson WP, et al. Inducing sustainable improvement in depression care in primary care practices. Joint Commission J Q Patient Saf. 2008;34:247–255.

Leveille SG, Huang A, Tsai SB, et al. Health coaching via an internet portal for primary care patients with chronic conditions: a randomized controlled trial. Med. Care. 2009;47:41–47.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2010 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Saur, C.D., Steffens, D.C. (2010). Adherence to Treatment for Depression. In: Bosworth, H. (eds) Improving Patient Treatment Adherence. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-5866-2_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-5866-2_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4419-5865-5

Online ISBN: 978-1-4419-5866-2

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)