Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic gastric bypass (LGB) surgery markedly increases percent excess weight loss (%EWL) and obesity-related co-morbidities. However, poor study quality and minimal exploration of clinical, behavioral, and psychosocial mechanisms of weight loss have characterized research to date.

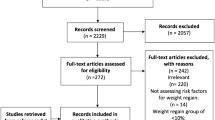

Methods

We conducted a comprehensive assessment of n=100 LGB patients surveyed 2–3 years following surgery using standardized measures.

Results

Mean %EWL at follow-up was 59.1±17.2%. This high level of weight loss was associated with a low rate of metabolic syndrome (10.6%), although medications were commonly used to achieve control. Mean adherence to daily vitamin and mineral supplements important to the management of LGB was only 57.6%, and suboptimal blood chemistry levels were found for ferritin (32% of patients), hematocrit (27%), thiamine (25%), and vitamin D (19%). Aerobic exercise level (R 2=0.08) and pre-surgical weight (R 2=0.04) were significantly associated with %EWL, but recommended eating style, fluid intake, clinic follow-up, and support group attendance were not. Psychosocial adjustment results showed an absence of symptomatic depression (0%), common use of antidepressant medications (32.0%), low emotional distress related to the post-surgical lifestyle (19.8±14.0; scale range 0–100), a high level of perceived benefit from weight loss in terms of functioning and emotional well-being (82.7±17.9; scale range 0–100), and a change in marital status for 26% of patients.

Conclusions

At 2–3 years following LGB surgery aerobic exercise, but not diet, fluid intake, or attendance at clinic visits or support groups, is associated with %EWL. Depression is symptomatically controlled by medications, lifestyle related distress is low, and marital status is significantly impacted.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Buchwald H. Obesity co-morbidities. In: Buchwald H, Cowan GSM, Pories WJ, editors. Surgical management of obesity. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007. p. 37–44.

Sturm R. Increases in morbid obesity in the USA: 2000–2005. Public Health. 2007;121:492–6.

American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) Fact Sheet. http://www.asbs.org/Newsite07/media/fact-sheet1_bariatric-surgery.pdf. Accessed 10 Apr 2009

Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724–37.

Garb J, Welch GW, Zagarins S, et al. Bariatric surgery for the treatment of morbid obesity: a meta-analysis of weight loss outcomes for laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding and laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2009;19(10):1447–55.

Oria HE. Long term follow-up and evaluation of results in bariatric surgery. In: Buchwald H, Cowan GSM, Pories WJ, editors. Surgical management of obesity. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007. p. 345–56.

Andrews G, LeMont D, Myers S. Caring for the surgical weight loss patient. Sierra Madre: Wheat Field; 2003.

McMahon M, Sarr M, Clark M, et al. Clinical management after bariatric surgery: value of a multidisciplinary team. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:S34–45.

Saunders R. Grazing: a high risk behavior. Obes Surg. 2004;14:98–102.

Poole N, AlAtar A, Kuhanendran D. Compliance with surgical after-care following bariatric surgery for morbid obesity: a retrospective study. Obes Surg. 2005;15:261–5.

Silver H, Torquati A, Jensen G. Weight, dietary, and physical activity behaviors two years after gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2006;16:859–64.

Colles S, Dixon J. Night eating syndrome: impact on bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2007;16:811–20.

DiRocco JD, Halverson JD, Planer J, et al. In: Buchwald H, Cowan GSM, Pories WJ, editors. Surgical management of obesity. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.

Santri H, Alverdy JC, Prachand VN. Patient selection for bariatric surgery. In: Buchwald H, Cowan GSM, Pories WJ, editors. Surgical management of obesity. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.

Magro DO, Geloneze B, Delfini R, et al. Long-term weight regain after gastric bypass: a 5-year prospective study. Obes Surg. 2008;6(18):648–51. 2006;16:811-820.

Welch G, Wesolowski C, Piepul P, et al. Perioperative symptoms following gastric bypass surgery. Bariatric Nursing and Surgical Patient Care. 2008;3(2):159–63.

Deitel M, Gawdat K, Melissas J. Reporting weight loss 2007. Obes Surg. 2007;17:565–8.

Third Report of the Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). National Cholesterol Education Program. National Institutes of Health Publication No. 01-3670, 2001.

Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery. National Institutes of Health. http://www.edc.gsph.pitt.edu/labs/Public/

Kincaid JP, Fishburne, RP, Rogers RL, et al. Derivation of new readability formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy enlisted personnel, Research Branch Report 8-75, Millington, TN: Naval Technical Training, U. S. Naval Air Station, Memphis; 1975.

Welch G, Wesolowski C, Piepul B, et al. Physical activity predicts weight loss following gastric bypass surgery: findings from a support group survey. Obes Surg. 2008;18(5):517–24.

Weinstein AR, Sesso HD, Lee IM, et al. Relationship of physical activity vs body mass index with type 2 diabetes in women. JAMA. 2004;292(10):1188–94.

Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(9):S498–504.

Wolf AM, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23:991–9.

Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report, 2008. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2008.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;35:509–21.

The Macarthur Initiative of depression and primary care. http://www.depression-primarycare.org

American Psychological Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-IV. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2000.

Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252:1905–7.

Kitchens JM. Does this patient have an alcohol problem? JAMA. 1994;272(22):1782–7.

Bernadt MW. Comparison of questionnaire and laboratory tests in the detection of excessive drinking and alcoholism. Lancet. 1982;6(8267):325–8.

SPSS. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). 10.0 Version. Chicago: SPSS Inc; 1999.

SAS. Statistical Analysis System (SAS). 9.1 Version. Cary: SAS Inc; 2005.

Mondolfi RN, Jones TM, Hyre AD, Raggi P, Muntner P. Comparison of percent of United States adults weighing>or=300 pounds (136 kilograms) in three time periods and comparison of five atherosclerotic risk factors for those weighing>or=300 pounds to those<300 pounds. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(11):1651–3.

Lee WJ, Huang M, Wang W, et al. Effects of obesity surgery on the metabolic syndrome. Arch Surg. 2004;139:1088–92.

Hatoum IJ, Stein HK, Merrifield BF, et al. Capacity for physical activity predicts weight loss after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obesity. 2009;17(1):92–9.

Lutfi R, Torquati A, Sekhar N. Predictors of success after laparoscopic gastric bypass: a multivariate analysis of socioeconomic factors. Surg Endosc. 2006;20(6):864–7.

van Hout GC, Verschure SK. Psychosocial predictors of success following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2005;15(4):552–60.

Dixon JB, O’Brien PE. Nutritional outcomes of bariatric surgery. In: Buchwald H, Cowan GSM, Pories WJ, editors. Surgical management of obesity. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007. p. 357–64.

Marcus J, Symmonds R, Rodriguez J, et al. Noncompliance with behavioral recommendations following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2005;15(4):546–51.

Odom J, Zalesin KC, Washington TL, et al. Behavioral predictors of weight regain after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2009. doi:10.1007/s11695-009-9895-6.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Bariatric Surgery Self-management Questionnaire (BSSQ) Subscales and Item Content

Appendix: Bariatric Surgery Self-management Questionnaire (BSSQ) Subscales and Item Content

Eating behaviors (EB):

-

1.

I ate a minimum of 5 mini meals or snacks during the day

-

2.

I ate slowly, putting my utensils or food down between bites

-

3.

It took about 20-30 minutes for me to eat my meals

-

4.

I chewed my food until it was a pureed consistency like baby food

-

5.

I used a bread and butter plate or dessert plate instead of a regular- sized plate for my meals

-

6.

I checked for feeling of a feeling of fullness after every bite

-

7.

I stopped eating immediately if I had any feelings of fullness or discomfort

-

8.

I used a baby spoon, fork, and knife instead of regular sized ones

Fluid intake (FI):

-

9.

I drank 48 ounces (six 8 oz glasses) or more of fluids during the day

-

10.

I only drank water, sugar-free beverages, skim milk, or 1% milk

-

11.

I sipped drinks slowly putting my drink down between sips

-

12.

I avoided using a straw to drink

-

13.

I carried a suitable drink with me at all times

-

14.

I did not rely on feeling thirsty as a signal to drink

-

15.

I checked my urine through the day to make sure it was pale yellow-to-clear in color showing good fluid intake

-

16.

I drank 30 minutes before my meal and waited until 30 minutes after my meal so that I separated my fluids from my solid foods

Physical activity (PA):

-

17.

I got 30-60 minutes of exercise 5 days or more in the past week (e.g., walking, exercise equipment at home, health club, class, etc)

-

18.

I built some exercise into my daily routines (I took the stairs, walked around the supermarket or mall before shopping, etc.)

-

19.

I built some weight training into my exercise program (hand weights, climbing stairs, weight machines, etc)

Dumping syndrome management (DSM):

-

20.

I read nutrition fact panels on food labels to look for high levels of sugar

-

21.

I avoided foods and beverages with 15 grams (3 tsp) of sugar or more a serving

-

22.

I avoided foods and beverages with sugar listed as one of the first three ingredients (glucose, maltose, dextrose, fructose, honey, molasses, corn syrup, brown sugar, cane sugar, confectionary sugar)

-

23.

I avoided sugar alcohols (mannitol, sorbitol, xylitol, lactitol) by looking at food labels as these cause cramping and diarrhea

Supplement Intake (SI):

-

24.

I took a multi-vitamin with minerals tablet every day

-

25.

I took 1000 to 1500 mg of calcium citrate or calcium carbonate with vitamin D every day

-

26.

I took a B-complex vitamin supplement every day

-

27.

I took my vitamin/calcium pills 4 hours or more apart to maximize absorption

Fruits, vegetables, and whole grain intake (FVW):

-

28.

I ate at least 5 fruits and vegetables every day

-

29.

I mostly chose whole grain breads, cereals, and crackers

-

30.

I mostly chose brightly colored fruits and vegetables (yellow, green, red, orange, blue, purple)

Protein Intake (PI):

-

31.

I ate 60-80 grams (2-3 oz) of protein every day (fish, eggs, chicken, turkey, beef, pork, ham, milk, peanut butter, beans, soy, tofu, lentils, cheese, nuts, yogurt, skim or 1% milk, or low sugar protein bars and shakes)

-

32.

I ate the protein on my plate first during meals and snacks

-

33.

I read food labels and chose the foods highest in protein and lowest in sugar

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Welch, G., Wesolowski, C., Zagarins, S. et al. Evaluation of Clinical Outcomes for Gastric Bypass Surgery: Results from a Comprehensive Follow-up Study. OBES SURG 21, 18–28 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-009-0069-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-009-0069-3