- 1School of Politics and Public Administration, Guangxi Normal University, Guilin, China

- 2School of Management, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China

- 3School of Social and Public Administration, East China University of Science and Technology, Shanghai, China

- 4Population Research Institute, Peking University, Beijing, China

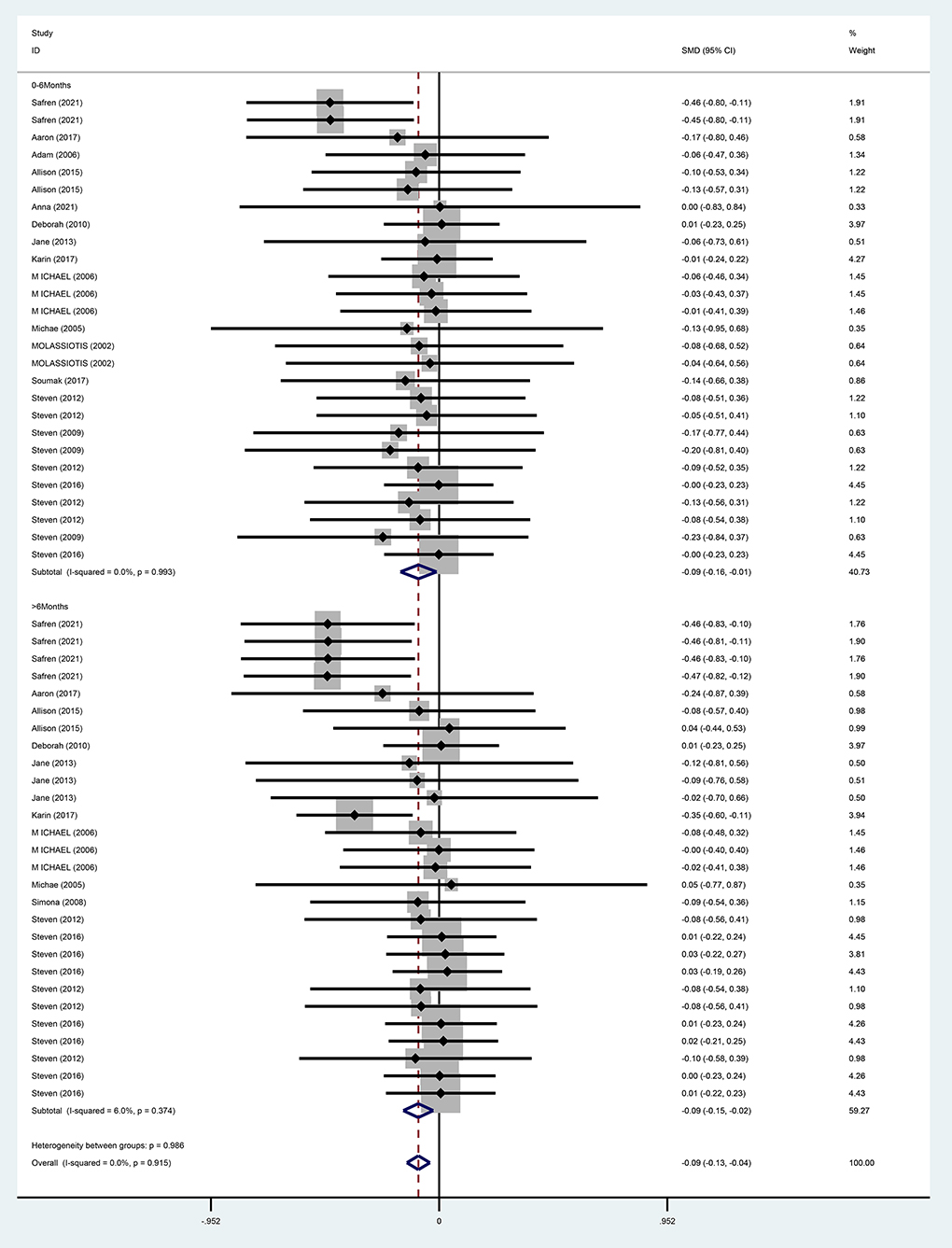

The incidence of depression is higher in PLWH (people living with HIV) than in the general population. It is of clinical significance to explore effective measures to improve depression in patients. But the available evidence is still quite limited. CBT (cognitive behavioral therapy) is considered to be one of the effective methods to improve depression, medication adherence and quality of life in PLWH. Therefore, this study aimed to systematically evaluate the effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on improving depressive symptoms and increasing adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) in people living with HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus). The Cochrane Library, Embase, PubMed, and Web of Science databases were searched by computer to collect randomized controlled trials on the effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on improving depression and increasing ART medication adherence in PLWH, and the retrieval time was from the inception of each database to January 10, 2022. Meta-analysis was performed by two researchers using Stata 15.0 software after screening the literature, extracting data and evaluating quality according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. A total of 16 studies with 1,998 patients were included. Meta-analysis results showed that CBT improved depressive symptoms in PLWH (SMD = −0.09, 95% CI [−0.13 to −0.04], P < 0.001) with better long-term (<6 months) depression improvement (SMD = −0.09, 95% CI [−0.15 to −0.02], P = 0.006) than short-term (0–6 months); the difference in improved ART medication adherence in the CBT group compared to the control group was not statistically significant (SMD = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.06 to 0.13], P = 0.490). There may be publication bias due to incomplete inclusion of literature as only published literature was searched. Cognitive behavioral therapy is effective in improving depressive symptoms in people living with HIV, with better long-term (>6 months) results than short-term (0–6 months).

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, ~37.7 million people (95% CI, 30.2–45.1 million) are infected with HIV (World Health Organization) (1). People living with HIV (PLWH) are more likely to suffer from mental health disorders than the general population (2). The incidence of depression is higher in PLWH than in the general population, and depression decreases ART medication adherence in PLWH which is key to the success of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) (3, 4). Some studies have shown that only 95% or more adherence to treatment can ensure the effectiveness of antiviral therapy (5, 6). However, adherence to medication among people living with HIV is not encouraging. A cross-sectional survey in Latin America showed that the overall adherence rate for PLWH was only 70% (7). It has also been documented that only 67.51% of PLWH achieve 100% medication adherence (8). Therefore, effective measures need to be explored to improve patients' depressive symptoms and promote ART medication adherence.

Given the high prevalence of depression in PLWH and its negative effects, more strategies and interventions have been implemented, such as medication and psychotherapy. Studies have found a significant correlation between depressed mood and treatment adherence, quality of life, and life expectancy in PLWH (9, 10). Therefore, psychological interventions in the treatment of depression in PLWH play a key role in the treatment of depression in PLWH. In recent years, CBT has been widely used by many researchers in the management of mental health of PLWH. CBT has been shown to be effective in improving adherence, depressive symptoms, stress, and quality of life in PLWH IDUs (injecting drug users), MSM (men who have sex with men), etc., (11–14) and more effective in reducing depressive symptoms and increasing ART medication adherence than other psychological intervention models (15). Therefore, this study examines the effect of CBT on the remission of depressive symptoms and adherence to ART medication in PLWH.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the methods of psychotherapy, which believes that irrational cognition and behavior can affect emotions and cause or exacerbate psychological and physical problems. CBT is a structured, problem-centered treatment approach that encompasses a wide range of interventions, making it difficult to give a single and clear definition. According to Christopher, CBT is based firstly on the idea that thoughts affect the individual's emotions and behaviors in response to events that occur; secondly, perceptions and interpretations of events are shaped by the individual's beliefs and assumptions; logical fallacies and cognitive distortions can occur in people experiencing psychological distress; CBT can modify the patient's bad thoughts and thus reduce psychopathology (16). Based on the above concepts, this meta-analysis defines CBT as follows: (1) PLWH (people living with HIV)associate their symptoms with distress, irrational thoughts and beliefs, and behaviors; (2) reassessment of cognitions, beliefs, or reasoning related to the target symptoms; (3) psychological interventions independent of other therapeutic measures, such as challenging habitual thinking patterns, listing evidence of false beliefs, giving alternative plausible and individualized explanations based on reasoning ability and personal experience and testing them in reality; (4) either case therapy or group therapy is available.

Currently, no evidence-based studies with a high level of evidence have been conducted on the effects of CBT on improving depression and increasing ART medication adherence in PLWH in spite of several studies on the effects of CBT on depression and medication adherence in PLWH. Much of the available evidence focuses on specific populations of people living with HIV, with few reports of systematic evaluation of people living with HIV as a whole. For example, one systematic review has focused on psychological interventions, including cognitive behavioral therapy for PLWH with common psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety. However, this review only presented the characteristics of the five included studies which were not processed by meta-analysis (17). Another meta-analysis focused on the intervention of CBT on depressive symptoms in PLWH, revealing the short-term effectiveness of CBT on depressive symptoms in PLWH (18). Studies have shown that a series of interventions through CBT can improve depression and quality of life for PLWH, with the best results for those in the latent phase of the disease (19). As for multiple studies on specific populations of people living with HIV, for instance, a systematic review of cognitive behavioral therapy to improve mental health in women with AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) including three studies measuring mental health QOL (quality of life) and stress demonstrated statistically significant improvement in reducing psychological distress, improving symptoms of depression, stress and QOL (15). Nevertheless, the efficacy of CBT for people living with HIV/AIDS has been predominantly characterized in men who have sex with men and was more pronounced when participants possessed higher education and treatment providers used cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (20, 21). Group-based psychosocial interventions based on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) may have a small effect on measures of depression, and this effect may last for up to 15 months after participation in the group sessions, but the clinical importance of this is unclear (22). Studies have also shown improvement in depressive symptoms among people living with HIV/AIDS in low- and middle-income countries (23). Taken together, the available evidence is still quite limited. The aim of this study was to systematically evaluate studies on depressive symptoms and ART medication adherence in PLWH so as to provide evidence-based medical evidence for CBT intervention in PLWH.

Methods

Literature search

Computer searches of the Cochrane Library, Embase, PubMed, and Web of Science databases were conducted to collect randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on improving depression and increasing medication adherence in PLWH, with the search time set from the inception of each database to January 10, 2022. For PubMed, the search strategy was to retrieve articles containing the terms PLWH, CBT, and RCT in the subject terms and free terms. A similar strategy was used when searching other databases Taking PubMed as an example, the specific search strategy is shown in Appendix.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

• Studies that met the following inclusion criteria were included in the meta-analysis.

• Subjects: patients aged 18 years or older with a confirmed HIV-positive diagnosis, including HIV-infected patients and patients with AIDS.

• Study design: randomized controlled trial (RCT) with no language restrictions.

• Interventions: the CBT group received conventional nursing or other psychological intervention plus CBT. The control group used conventional nursing or other psychological intervention models.

• Outcome measures: (1) Depression: the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD), Center for Epidemiological Survey-Depression Scale (CES-D), Profile of Mood States (POMS), the Clinical Global Impression (CGI), and the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) were used for assessment. (2) ART medication adherence: self-report, the Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS), the Simplified Medication Adherence Questionnaire (SMAQ), and Wispill Technologies were used for evaluation.

Exclusion criteria for meta-analysis were as follows:

• Literature reviews, systematic reviews, case reports, or study protocols.

• Studies unrelated to the topic.

• Non-CBT research interventions.

• Study subjects without PLWH or depression.

Data extraction

Each included study was coded by two researchers and the Excel spreadsheet was completed according to the following details: author, year of publication, country, participant characteristics, specific descriptions of the intervention and control groups, etc. Data were independently extracted and cross-checked by two investigators according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The extracted information included study subjects, interventions, control measures, intervention duration, follow-up duration, outcome indicators, and evaluation time of outcome indicators. All included studies were independently evaluated and differences were discussed until consensus was reached.

Quality assessment

Two investigators independently screened the literature according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, extracted and cross-checked the data, and assessed the literature quality. The risk of bias assessment tool for systematic reviews of interventions from the Cochran Collaborative (version 5.1.0) (24) was adopted to evaluate the methodological quality of the included studies.

Data analysis

Meta-analysis was performed using Stata 15.0 software. For continuous data, the mean difference (MD) was used as the effect analysis statistic if the results were obtained using the same measurement tool, and the standardized mean difference (SMD) was used as the effect analysis statistic if different measurement tools were employed for the same variables. Chi-square test was adopted to determine whether there was statistical heterogeneity among the results. If P ≥ 0.1 and I2 < 50%, multiple similar studies were considered to be homogenous, and a fixed-effects model was used for meta-analysis. If P < 0.1 and I2 ≥ 50% with clinical homogeneity, a random-effects model was selected.

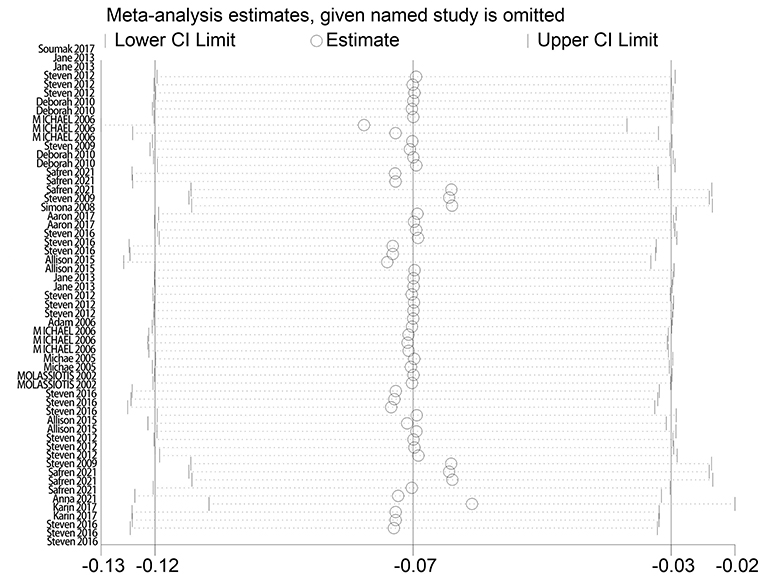

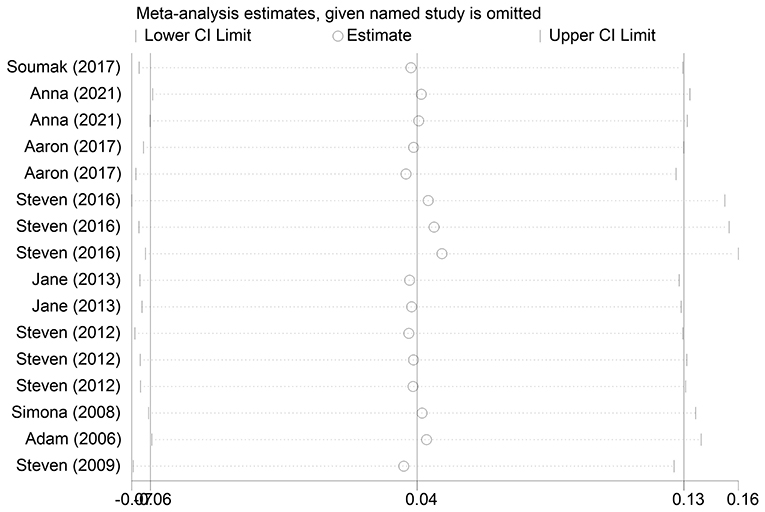

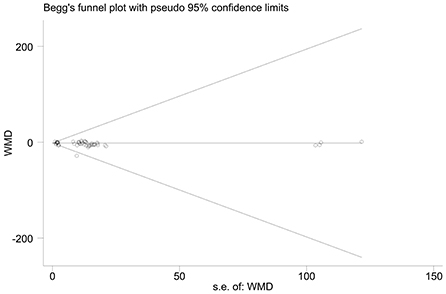

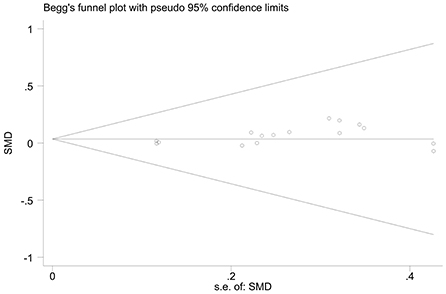

The effect extent of the combined effect size on depressive symptoms and ART medication adherence and the robustness of the results were explored by the one-by-one exclusion method. No significant changes in the results occurred after the exclusion of the two study groups, indicating low sensitivity and relatively robust and reliable results (Figures 1, 2). Begg's test was used to detect the publication bias of the two groups. In the depressive symptoms group, P = 0. 0.107 for Begg's test, and thus the publication bias was excluded (Figure 3); P = 0.065 for Begg's test in the ART medication adherence group, thereby excluding the publication bias (Figure 4).

Subgroup analysis grouping

On depressive symptoms, some literature has shown differences of CBT in long-term and short-term interventions for depressive symptoms in PLWH populations (25). Studies also have demonstrated high heterogeneity between different depression scales so that the use of intervention duration and different scales as a basis for subgroup analysis grouping in subgroup analysis needs to be introduced (26). In terms of ART medication adherence, the results of some studies have shown that the duration of follow-up in PLWH is directly related to patients' tolerance of the medication and adherence to regular medication (27), and thus subgroups of length of follow-up will be used to analyze ART medication adherence in PLWH in order to observe the extent to which length of follow-up affects medication adherence.

Results

Study selection

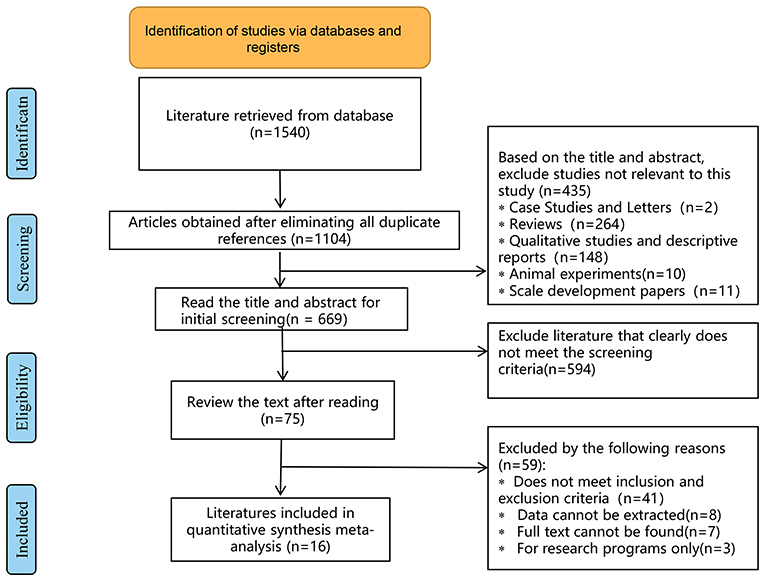

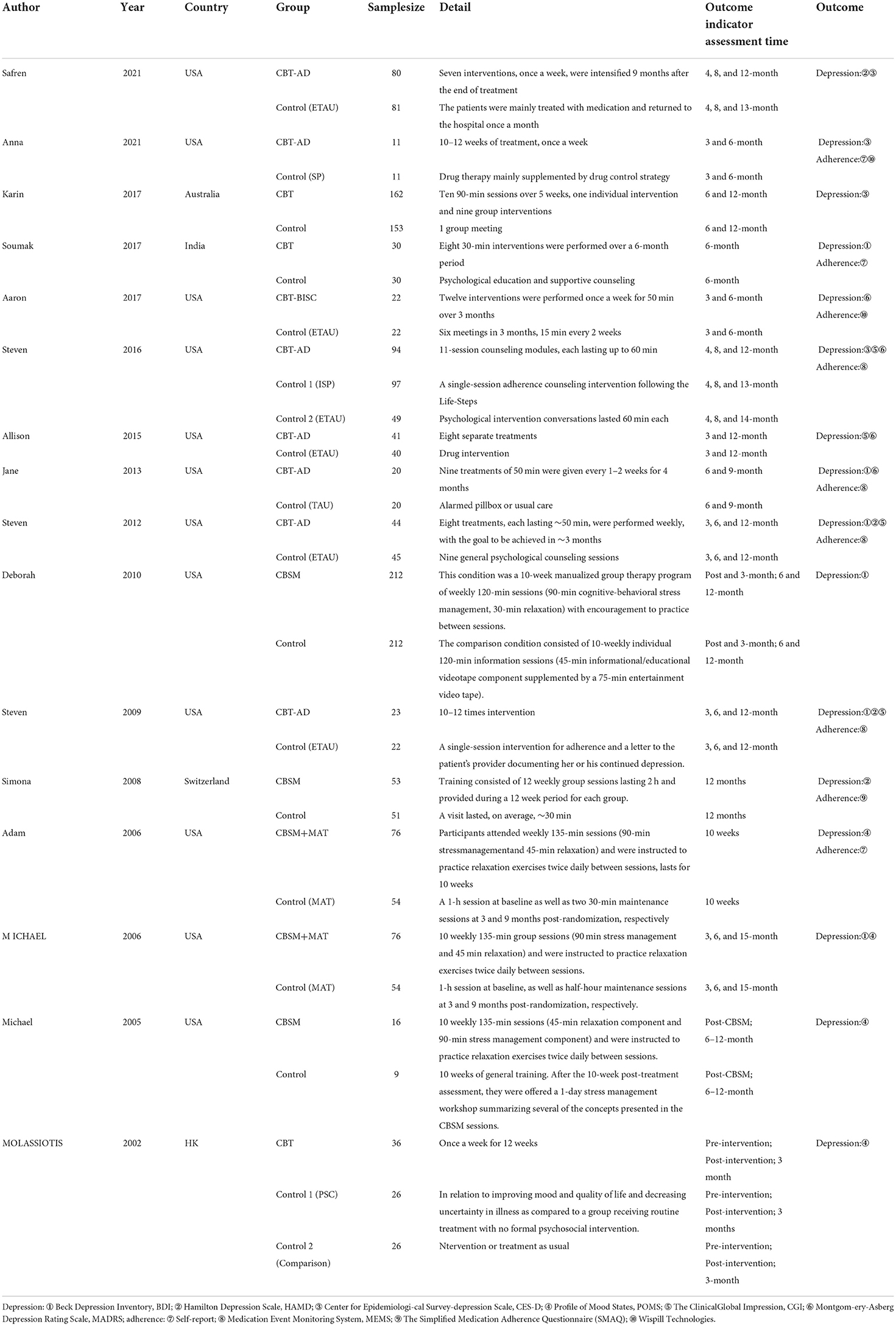

A total of 1,540 relevant articles were initially retrieved, and after stratification screening, 16 studies (13, 28–42) with a total of 1,998 patients were finally included. The literature screening process and results are shown in Figure 5. The 16 studies enrolled 1,998 patients from the United States, Australia, China, Nigeria, India, and Switzerland. The CBT group received 6 to 12 times of intervention, with each intervention lasting from 30 to 150 min. The duration of intervention lasted varied from 6 weeks to 4 months, and the follow-up lasted from 3 months to 36 weeks. The basic information of the included studies is detailed in Table 1, and the methodological quality evaluation of the included studies is shown in Table 2.

Study outcomes

Depression

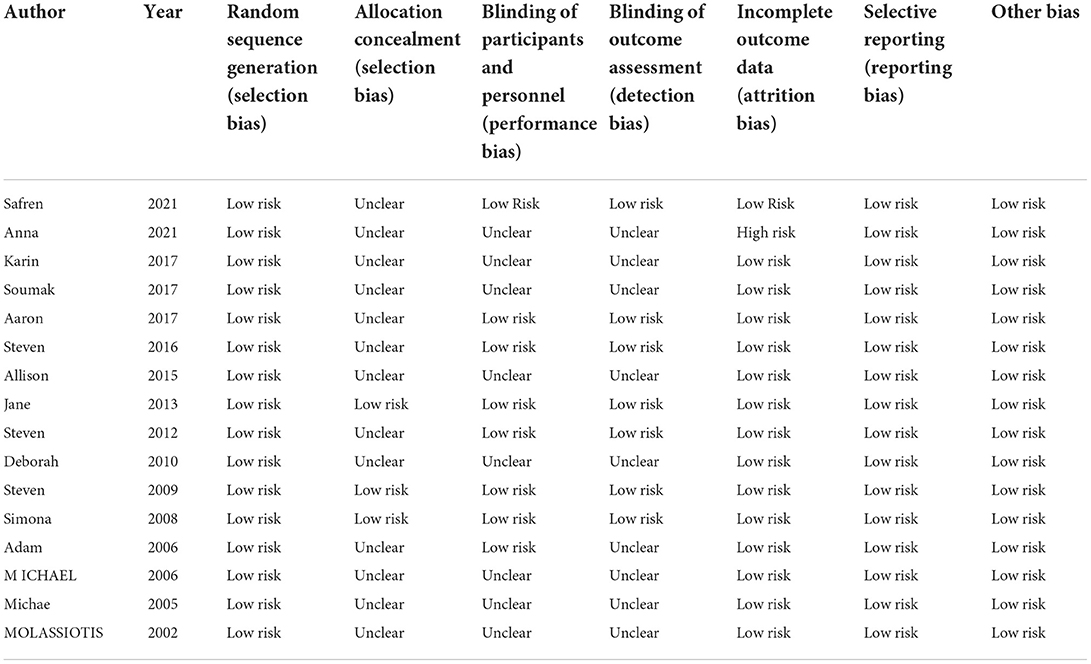

For the overall effect on depression, 15 studies (13, 28–37, 39–42) evaluated the effect of CBT on depression in the short term (0–6 months) using BDI, CES-D, HAMD, POMS, CGI, and MADRS, and 11 (13, 28, 30, 32–36, 38, 40, 41) evaluated the effect of CBT on depression in the long term (>6 months, the same below) using BDI, HAMD, POMS, MADRS, CGI, and CES-D, respectively. And the above studies were analyzed in subgroups according to the duration of the intervention effect. Since different scales were adopted for evaluation in each study, the standardized mean difference was used as the effect analysis statistic. Meta-analysis results using the random-effects model showed that the overall difference in depression improvement between the CBT group and control group was statistically significant (SMD = −0.09, 95% CI [−0.13 to −0.04], P < 0.001) (Figure 6). Further subgroup analysis indicated that the CBT group improved better than the control group in depression in both follow-up periods, the difference was statistically significant in the short term (0–6 months) (SMD = −0.09, 95% CI [−0.16 to 0.01], P = 0.025); in the long term (<6 months), the difference in depression improvement between the two groups was statistically significant (SMD = −0.09, 95% CI [−0.15 to −0.01], P = 0.006) (Figure 7).

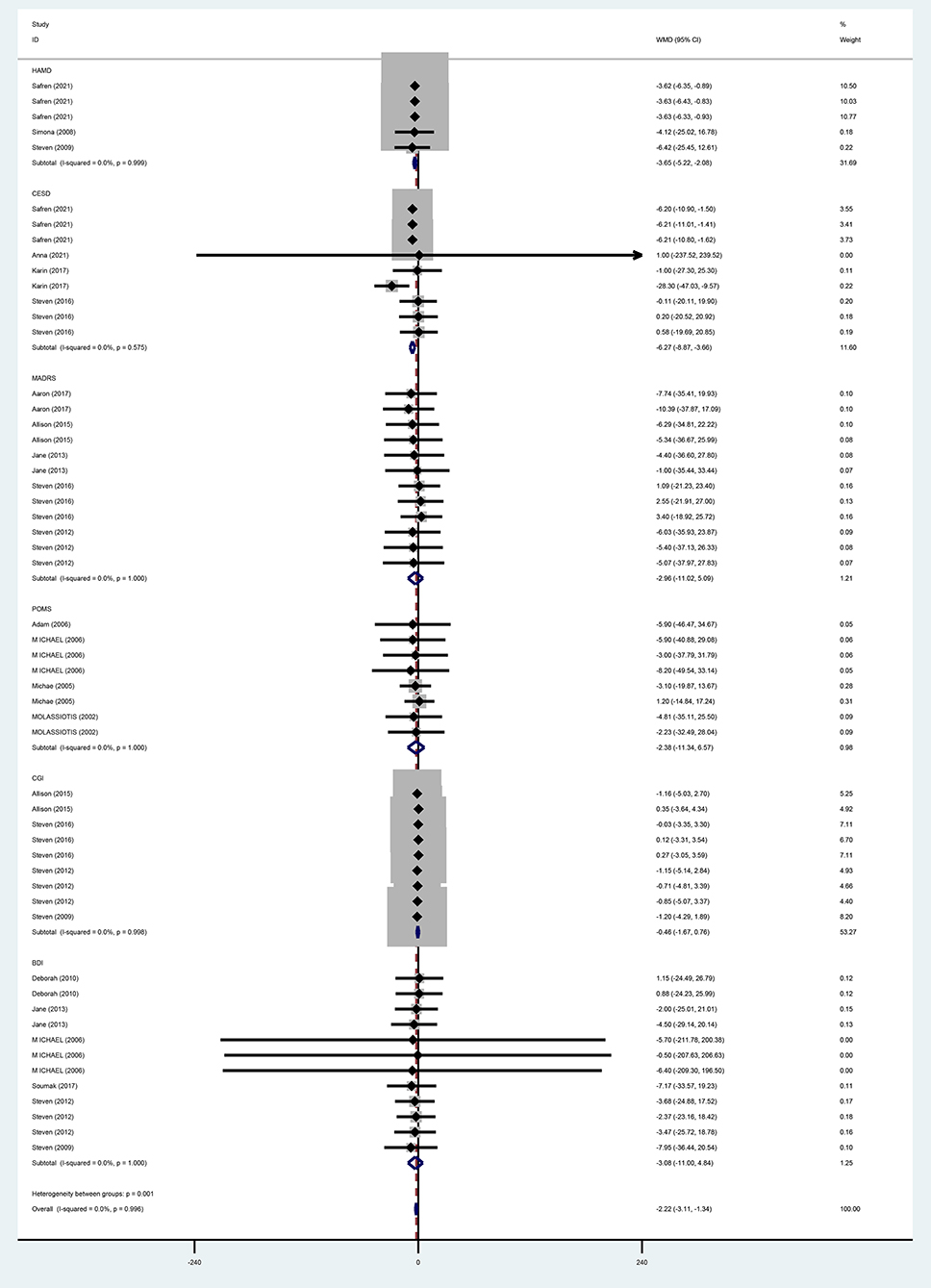

For the effects of CBT on depression measured by different scales, six studies (13, 31, 35–37, 40) adopted BDI, and meta-analysis results using a fixed-effects model showed that the improvement of depression in the CBT group was not better than that in the control group and that the difference was not statistically significant (WMD = −3.08, 95% CI [−11.00 to 4.84], P = 0.446). With three studies (28, 37, 38) using HAMD, meta-analysis results by a fixed-effects model demonstrated that the improvement in depression was better in the CBT group than in the control group and the difference was statistically significant (WMD = −3.65, 95% CI [−5.22 to 2.08], P = 0.000). MADRS was used in five studies (28–32), and the meta-analysis using a fixed-effects model showed that CBT improved depression better than the control group, while the difference was not statistically significant (WMD = −2.96, 95% CI [−11.02 to −5.09], P = 0.471). POMS was adopted in four (39–42) studies, and the meta-analysis using the fixed-effects model indicated that improvement in depression was better in the CBT group than in the control group, but the difference was not statistically significant (WMD = −2.38, 95% CI [−11.34 to 6.57], P = 0.602). With four studies (13, 33, 34, 37) using CGI, meta-analysis results by a fixed-effects model showed that the CBT group improved depression better than the control group, but the difference was not statistically significant (WMD = −0.46, 95% CI [−1.67 to 0.76], P = 0.459). Four studies (28–30, 33) adopted CESD, and the meta-analysis using a fixed-effects model showed that the improvement in depression was better in the CBT group than in the control group with a statistically significant difference (WM = −6.27, 95% CI [−8.87 to −3.66], P = 0.000) (Figure 8).

Adherence

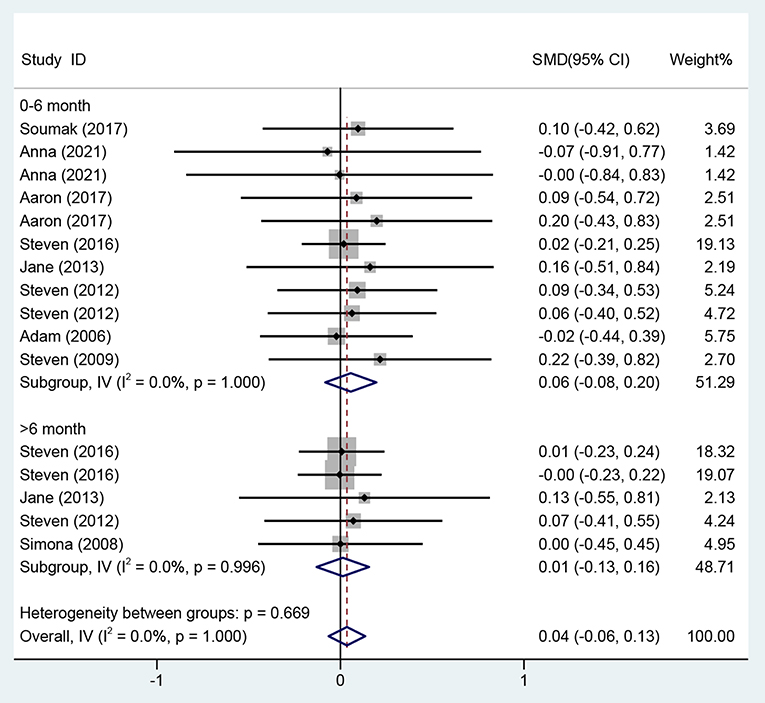

As for the overall effect on ART medication adherence, the meta-analysis results using the fixed-effects model showed that there was no statistically significant difference in the improvement of ART medication adherence in the CBT group compared with the control group (SMD = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.06 to 0.13], P = 0.490) (Figure 9).

Regarding the effects on ART medication adherence from 0 to 6 months, eight studies (13, 29–31, 33, 35, 37, 39) evaluated the effects of CBT on ART medication adherence over the period of 0–6 months using different adherence instruments for evaluation, so the standardized mean difference was used as the effect analysis statistic. Meta-analysis of the fixed-effects model revealed no statistically significant difference in the improvement of ART medication adherence in the CBT group compared with the control group (SMD = 0.06, 95% CI [−0.08 to 0.20], P = 0.428) (Figure 9).

Four studies (13, 33, 35, 38) on the effects on ART medication adherence over a period of >6 month adopted different evaluation methods, and the standardized mean difference was used as the effect analysis statistic. The meta-analysis results of the fixed-effects model showed no statistically significant difference in the improvement of adherence in the CBT group compared with the control group (SMD = 0.01, 95% CI [−0.13 to 0.16], P = 0.860) (Figure 9).

Discussion

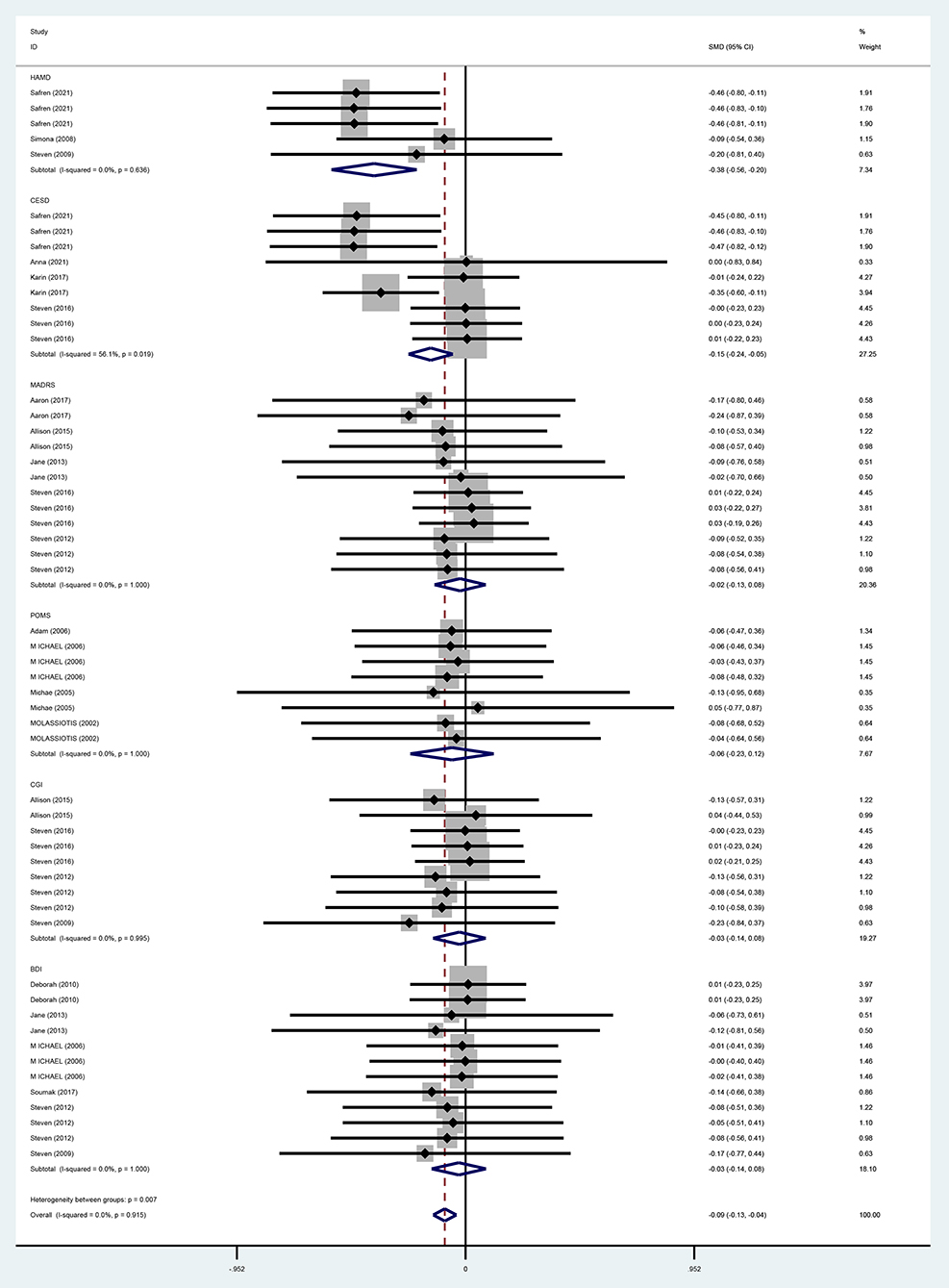

A total of 16 studies with 1,998 patients were included in this systematic evaluation. Two researchers evaluated the risk of bias of included RCTs using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviewers (version 5.1.0), RCT risk of bias assessment tool. Evaluation indicators include: (1) sequence generation (selection bias); (2) allocation concealment (selection bias); (3) blinding of patients and personnel (performance bias); (4) blinding of outcome assessors (detection bias); (5) incomplete outcome data (attrition bias); (6) elective reporting (reporting bias); (7) other bias. Each indicator contains three levels: low risk, unclear and high risk. Disagreement during the evaluation process may be referred to a third party for determination. The overall quality of the included studies was good, suggesting the reliability of the combined data in this meta-analysis (Table 2).

Meta-analysis results suggested that CBT could improve depressive symptoms in PLWH. Meta-analysis results from this systematic evaluation of studies indicated that CBT improved depression in PLWH in general, with more significant long-term (>6 months) effects than short-term (0–6 months). This result is consistent with a study by Tobin et al. (30), which administered 3-month CBT to 165 PLWH (6 ≤ CES-D ≤ 40) in a randomized controlled trial with nine group sessions and one individual session. A comparison of baseline, 6 and 12 months CES-D scores revealed that CES-D depression scores were lower than baseline levels in both groups during follow-up, and the CES-D score of 17.1 at the 12-month follow-up was less than the 19.2 at 6 months, indicating a good long-term benefit of CBT. There is evidence (43) that 6 months is a critical period for achieving significant efficacy of antiviral therapy in PLWH. Among the disease factors, CD4 (Cluster of Differentiation 4) + T lymphocytes <200/μl and disease stage of AIDS are risk factors for depression in PLWH, suggesting an association between disease severity and depression. StuWMDdies have found that the decrease of CD4 + T lymphocytes will aggravate the depressive symptoms of PLWH (44), while PLWH in a depressed state have a significantly greater decline in CD4 + T lymphocytes than those without depression (45), and the two are correlated and interact with each other. PLWH phase are at increased risk of depression with the onset of various somatic symptoms and opportunistic infections (46, 47). Hence, the more pronounced improvement in depression over 6 months in this systematic analysis may also be related to the fact that PLWH have undergone 6 months of antiretroviral therapy.

When studies were included in the subgroup analysis by different measurement scales, CBT improved depression in PLWH when depression was evaluated by HAMD, MADRS, CES-D, POMS, and CGI, while CBT did not show an effect of improving depression in PLWH when depression was evaluated by BDI. The slight differences in the above results may be related to some errors in the evaluation of depression by different scales, or the adoption of a group-based treatment model in the CBT group in some of the studies. A meta-analysis showed that CBT-based group psychological interventions had a small effect on measures of depression in PLWH, lasting until the end of the 15-month follow-up; the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was used in most previous studies, with a maximum score of 63, and at the end of the intervention, the mean score for the treatment group was only 1.4 points lower than that of the control group (48). This may be related to the fact that group therapy cannot take into account the cultural background of every participant and the particularity of the disease makes PLWH less active in participating. For individual treatment, the intervenor can choose a more targeted treatment plan according to the different cultural and personality characteristics, interests and hobbies of each patient, so as to make the treatment effect more significant.

CBT aims to help clients better cope with their emotional distress by changing their irrational thinking and behavior patterns (49). When conducting CBT, the medical staff and clients work jointly to identify the problem to be solved, develop solutions for different situations, make decisions on what to adopt, and formulate implementation plans (13). Thus, CBT helps clients to better manage the problems they face and thereby improve depression. The long-term (>6 months) effects of CBT on PLWH depression are more significant than short-term (0–6 months), indicating that it takes time to maintain the effects of CBT interventions.

The results of this systematic evaluation suggest that the effects of CBT on improving antiretroviral therapy (ART) medication adherence in PLWH are unclear. This may be due to the fact that the medication taking behavior of PLWH is influenced by various factors, such as the patient's personal factors, disease factors, psychosocial factors, and the doctor-patient relationship, all of which can affect the patient's adherence (50). Furthermore, as no uniform conclusion has been reached on the factors influencing ART adherence among PLWH due to differences in social environment, adherence assessment indicators, study population, and study methods (51, 52), the improvement in depressive symptoms may have had only a partial effect on ART medication adherence, thereby resulting in a non-significant overall effect. Meta-analysis results based on eight short-term effect RCTs and four long-term effect RCTs showed that the long-term (>6 months) effect of CBT on improving antiretroviral therapy (ART) medication adherence in PLWH was better than the short-term (0–6 months) effect. This is consistent with the findings of a meta-analysis in China suggesting that CBT has a long-term favorable effect on improving medication adherence and PLWH (53).

The meta-analysis by Dimatteo et al. showed that depressed clients were three times more likely to not comply with medical treatment recommendations compared with non-depressed patients (54). Therefore, depression is one of the important risk factors for treatment non-adherence in PLWH. The above results may be attributed to the fact that CBT, as a psychological intervention mode, requires a longer period of intervention to prevent PLWH from gradually stopping changing, so as to improve clients self-management ability and thus ART medication adherence (55). The maximum follow-up for ART medication adherence included in this systematic evaluation was 12 months, and longer interventions may still be needed.

Limitations

This systematic review of included studies may have some heterogeneity in sample and methodology such as sample size, article quality, and outcome measures; the content, starting time, frequency and duration of intervention programs varied greatly; there were also great differences in the evaluation methods and scales of outcome indicators. Meanwhile, there may be publication bias due to incomplete inclusion of literature as only published literature was searched.

Conclusions

CBT is an effective treatment for depression, and in this systematic review, we have found that CBT has a potential improvement effect on PLWH combined with depression, but the improvement of ART medication adherence needs further study. Therefore, policymakers should provide policies and funding to support CBT interventions for PLWH depression and ART medication adherence, and health care providers should consider CBT in PLWH to improve depression in PLWH. The short-term effect of CBT on improving ART medication adherence in PLWH remains unclear, and thus it is recommended that policymakers and healthcare providers invest in multi-center RCTs with large sample sizes to confirm the effect of CBT on improving medication antiretroviral therapy (ART) medication adherence in PLWH.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

KQ and JZ wrote the main manuscript, fully participated in all analyses, and contributed to the study concept and design. LL and YC participated in literature search, data extraction, and quality assessment. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the scientific research start-up funds (Grant No. DC2200002888).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.990994/full#supplementary-material

References

1. WHO. Global Summary of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic 2020. (2020). Available online at: http://www.who.int/hiv/data/en/ (accessed May 28, 2022).

2. Brown LA, Majeed I, Mu W, McCann J, Durborow S, Chen S, et al. Suicide risk among persons living with HIV. AIDS Care. (2021) 33:616–22. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2020.1801982

3. Mao Y, Qiao S, Li X, Zhao Q, Zhou Y, Shen Z. Depression, social support, and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV in Guangxi, China: a longitudinal study. AIDS Educ Prev. (2019) 31:38–50. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2019.31.1.38

4. Yousuf A, Mohd Arifin SR, Musa R, Md Isa ML. Depression and HIV disease progression: a mini-review. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. (2019) 15:153–9. doi: 10.2174/1745017901915010153

5. Yan CL, Wu QW, Wang FX, He YH, Zhang FD, Gao LJ, et al. Regression analysis of the current status of adherence to antiretroviral therapy and factors influencing quality of life among HIV patients. Chin J Soc Med. (2012) 29:1–13. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5625.2012.06.015

6. Hu Y. Zhong X-N, Peng B, Zhang Y, Liang H, Dai J-H, et al. Associations between perceived barriers and benefits of using HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and medication adherence among men who have sex with men in Western China. BMC Infect Dis. (2018) 18:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3497-7

7. Sweileh WM. Global research output on HIV/AIDS-related medication adherence from 1980 to 2017. BMC Health Serv Res. (2018) 18:765. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3568-x

8. Li C, Hu JH, Yang XH, Chen XY. Effect of using smart electronic pill box on HAART medication adherence during pregnancy in HIV-infected pregnant women. Chin J AIDS STD. (2020) 26:1–13. doi: 10.13419/j.cnki.aids.2020.02.10

9. Camargo CC, Cavassan NRV, Tasca KI, Meneguin S, Miot HA, Souza LR. Depression and coping are associated with failure of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. (2019) 35:1181–8. doi: 10.1089/aid.2019.0050

10. Krumme AA, Kaigamba F, Binagwaho A, Murray MB, Rich ML, Franke MF. Depression, adherence and attrition from care in HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2015) 69:284–9. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204494

11. Been SK, Schadé A, Bassant N, Kastelijns M, Pogány K, Verbon A. Anxiety, depression and treatment adherence among HIV-infected migrants. AIDS Care. (2019) 31:979–87. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2019.1601676

12. Wang L. Effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on the quality of survival of patients with HIV. Chin J Clin Rational Drug Use. (2017) 31:2. doi: 10.15887/j.cnki.13-1389/r.2017.31.080

13. Steven AS, Jacqueline RB, Michael WO, Michael DS, Mark HP. Cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected injection drug users: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2012). 80:404. doi: 10.1037/a0028208

14. Pu H, Hernandez T, Sadeghi J, Cervia JS. Systematic review of cognitive behavior therapy to improve mental health of women living with HIV. J Invest Med. (2020) 68:30–6. doi: 10.1136/jim-2019-000996

15. Yan L, Guo L, Chen JH, Gao BH, Lv JN. Current status of psychological intervention methods and applications for patients with HIV/AIDS. Chin J AIDS STD. (2021) 27:4. doi: 10.13419/j.cnki.aids.2021.12.29

16. Christopher DH, Irene C, Alan M, Claire BI. Cognitive behavior therapy vs. other psychosocial treatments for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (2012) 38:908–10. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs090

17. Chibanda D, Cowan FM, Healy JL, Abas M, Lund C. Psychological interventions for common mental disorders for people living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. (2015) 20:830–9. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12500

18. Shi Y, Zhao M, Chen S, Wang S, Li H, Ying J, et al. Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on people living with HIV and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Health Med. (2019) 24:578–94. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2018.1549739

19. Doerfler RE, Goodfellow L. Brief exposure to cognitive behavioral therapy reduces side-effect symptoms in patients on antiretroviral therapy. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. (2016) 27:455–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2016.02.010

20. Yu Y, Wang X, Wu Y, Weng W, Zhang M, Li J, et al. The benefits of psychosocial interventions for mental health in men who have sex with men living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. (2022) 22:440. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04072-1

21. Himelhoch S, Medoff DR, Oyeniyi G. Efficacy of group psychotherapy to reduce depressive symptoms among HIV-infected individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. (2007) 21:732–9. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0012

22. van der Heijden I, Abrahams N, Sinclair D. Psychosocial group interventions to improve psychological well-being in adults living with HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2017). 3:Cd010806. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010806.pub2

23. Asrat B, Schneider M, Ambaw F, Lund C. Effectiveness of psychological treatments for depressive symptoms among people living with HIV/AIDS in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2020) 270:174–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.068

24. Shuster JJ. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. (2011). Available online at: http://handbook.cochrane.org/ (accessed May 26, 2022).

25. Andersen LS, Magidson JF, O'Cleirigh C, Remmert JE, Kagee A, Leaver M, et al. A pilot study of a nurse-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy intervention (Ziphamandla) for adherence and depression in HIV in South Africa. J Health Psychol. (2018) 23:776–87. doi: 10.1177/1359105316643375

26. Fried EI. The 52 symptoms of major depression: lack of content overlap among seven common depression scales. J Affect Disord. (2017) 208:191–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.019

27. Xu XM, Qin YL, Chen Q, Hu YS. Exploration of follow-up time and medication adherence in patients with AIDS. J Nurses Train. (2011) 26:2. doi: 10.16821/j.cnki.hsjx.2011.07.014

28. Safren SA, O'Cleirigh C, Andersen LS, Magidson JF, Lee JS, Bainter SA, et al. Treating depression and improving adherence in HIV care with task-shared cognitive behavioural therapy in Khayelitsha, South Africa: a randomized controlled trial. J Int AIDS Soc. (2021) 24:e25823. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25823

29. Junkins A, Psaros C, Ott C, Azuero A, Lambert CC, Cropsey K, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary impact of telemedicine-administered cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression among African American women living with HIV in the rural South. J Health Psychol. (2021) 26:2730–42. doi: 10.1177/1359105320926526

30. Tobin K, Davey-Rothwell MA, Nonyane BAS, Knowlton A, Wissow L, Latkin CA, et al. RCT of an integrated CBT-HIV intervention on depressive symptoms and HIV risk. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0187180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187180

31. Chattopadhyay S, Ball S, Kargupta A, Talukdar P, Roy K, Talukdar A., et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy improves adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients: a prospective randomized controlled trial from eastern India. Int J HIV-Relat Probl. (2017) 16:89–95. doi: 10.5114/hivar.2017.67303

32. Blashill AJ, Safren SA, Wilhelm S, Jampel J, Taylor SW, O'Cleirigh C, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for body image and self-care (CBT-BISC) in sexual minority men living with HIV: a randomized controlled trial. Health Psychol. (2017) 36:937–46. doi: 10.1037/hea0000505

33. Safren SA, Bedoya CA, O'Cleirigh C, Biello KB, Pinkston MM, Stein MD, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy for adherence and depression in patients with HIV: a three-arm randomised controlled trial. Lancet HIV. (2016) 3:e529–38. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(16)30053-4

34. Labbe AK, O'Cleirigh CM, Stein M, Safren SA. Depression CBT treatment gains among HIV-infected persons with a history of injection drug use varies as a function of baseline substance use. Psychol Health Med. (2015) 20:870–7. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2014.999809

35. Simoni JM, Wiebe JS, Sauceda JA, Huh D, Sanchez G, Longoria V., et al. A preliminary RCT of CBT-AD for adherence and depression among HIV-positive Latinos on the US-Mexico border: the Nuevo Día study. AIDS Behav. (2013) 17:2816–29. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0538-5

36. Jones DL, Ishii Owens M, Lydston D, Tobin JN, Brondolo E, Weiss SM. Self-efficacy and distress in women with AIDS: the SMART/EST women's project. AIDS Care. (2010) 22:1499–508. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.484454

37. Safren SA, O'Cleirigh C, Tan JY, Raminani SR, Reilly LC, Otto MW, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected individuals. Health Psychol. (2009) 28:1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0012715

38. Berger S, Schad T, von Wyl V, Ehlert U, Zellweger C, Furrer H, et al. Effects of cognitive behavioral stress management on HIV-1 RNA, CD4 cell counts and psychosocial parameters of HIV-infected persons. AIDS. (2008) 22:767–75. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f511dc

39. Carrico AW, Antoni MH, Duran RE, Ironson G, Penedo F, Fletcher MA, et al. Reductions in depressed mood and denial coping during cognitive behavioral stress management with HIV-Positive gay men treated with HAART. Ann Behav Med. (2006) 31:155–64. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3102_7

40. Antoni MH, Carrico AW, Durán RE, Spitzer S, Penedo F, Ironson G, et al. Randomized clinical trial of cognitive behavioral stress management on human immunodeficiency virus viral load in gay men treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. Psychosom Med. (2006) 68:143–51. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000195749.60049.63

41. Antoni MH, Cruess DG, Klimas N, Carrico AW, Maher K, Cruess S, et al. Increases in a marker of immune system reconstitution are predated by decreases in 24-h urinary cortisol output and depressed mood during a 10-week stress management intervention in symptomatic HIV-infected men. J Psychosom Res. (2005) 58:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.05.010

42. Molassiotis A, Callaghan P, Twinn SF, Lam SW, Chung WY Li CK. A pilot study of the effects of cognitive-behavioral group therapy and peer support/counseling in decreasing psychologic distress and improving quality of life in Chinese patients with symptomatic HIV disease. AIDS Patient Care STDS. (2002) 16:83–96. doi: 10.1089/10872910252806135

43. World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Testing, Treatment, Service Delivery and Monitoring: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. Geneva: World Health Organization (2021).

44. Shi Y, Yang C, Xu L, He Y, Wang H, Cao J, et al. CD4+ T cell count, sleep, depression, and anxiety in people living with HIV: a growth curve mixture modeling. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. (2020) 31:535–43. doi: 10.1097/JNC.0000000000000112

45. Hellmuth J, Colby D, Valcour V, Suttichom D, Spudich S, Ananworanich J, et al. Depression and anxiety are common in acute HIV infection and associate with plasma immune activation. AIDS Behav. (2017) 21:3238–46. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1788-4

46. Duko B, Geja E, Zewude M. Mekonen SJA. Prevalence and associated factors of depression among patients with HIV/AIDS in Hawassa, Ethiopia, cross-sectional study. Ann General Psychiatry. (2018) 17:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12991-018-0215-1

47. Tesfaw G, Ayano G, Awoke T, Assefa D, Birhanu Z, Miheretie G, et al. Prevalence and correlates of depression and anxiety among patients with HIV on-follow up at Alert Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry. (2016) 16:368. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1037-9

48. Tareke M, Addisu F, Abate A. Depression among patients attending antiretroviral treatment program in public health facilities in Bahir Dar City, Ethiopia. J Affect Disord. (2018) 232:370–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.078

49. Jones C, Hacker D, Meaden A, Cormac I, Irving CB, Xia J, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy plus standard care vs. standard care plus other psychosocial treatments for people with schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2018) 11:Cd008712. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007964.pub2

50. Wang HJ, Wang JQ, Hu LM. Gene structure and function of HIV and pathogenesis. J Cell Biol. (2002). 24:5. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-7666.2002.06.005

51. Li H, Wang Z, Xu JJ, Cui WG, Chu ZX, Hu HQ. Analysis of HIV/ AIDS related discrimination and its correlates with compliableness in using anti-virus treatment. Crimination and its correlates with compliableness in using antivirus drug and other factor. J Med Res. (2013) 42:3. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-548X.2013.03.007

52. Chen YX, Liu ZL Li XM, Yuan XQ, Fu Y, Gao MX, et al. Analysis of the current situation and factors influencing medication adherence among HIV/AIDS patients. Chin J AIDS STD. (2015) 21:5. doi: 10.13419/j.cnki.aids.2015.04.04

53. Fu L, Wu MB, Yan H. Systematic evaluation of the effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on depression, medication adherence and quality of life in patients with HIV infection and AIDS. Chin J Evidence Based Med. (2014) 14:9. doi: 10.7507/1672-2531.20140124

54. DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Int Med. (2000) 160:2101–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101

Keywords: cognitive behavioral therapy, Human Immunodeficiency Virus, depression, medication adherence, meta-analysis

Citation: Qin K, Zeng J, Liu L and Cai Y (2022) Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on improving depressive symptoms and increasing adherence to antiretroviral medication in people with HIV. Front. Psychiatry 13:990994. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.990994

Received: 11 July 2022; Accepted: 28 October 2022;

Published: 09 November 2022.

Edited by:

Veena Kumari, Brunel University London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Han Qi, Capital Medical University, ChinaItziar Familiar, Michigan State University, United States

Copyright © 2022 Qin, Zeng, Liu and Cai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Keke Qin, qinkeke@stu.gxnu.edu.cn

Keke Qin

Keke Qin Jiale Zeng

Jiale Zeng Li Liu3

Li Liu3 Yumei Cai

Yumei Cai