Abstract

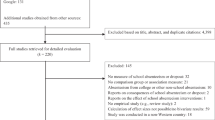

Early childhood disruptive behaviors are common mental health problems among American youth, and if poorly-managed, pose costly psychological and societal burdens. Outcomes accountability systems in clinical practice are vital opportunities to optimize early intervention for common mental health problems; however, such systems seem rare. A scoping review was conducted to summarize the current availability of outcomes accountability systems in clinical programs addressing early childhood disruptive behaviors, particularly in the US. We used PsycINFO to identify peer-reviewed literature published in English from 2005 to 2021, from which we selected 23 publications from the US, UK, and Netherlands on outcomes accountability systems within clinical programs treating common childhood mental health problems. Only 3 out of 23 publications described outcomes accountability efforts specifically for early childhood problems. Within the 3 studies, only one UK-based study specifically targeted early childhood disruptive behaviors. We did not find publications specifically describing outcomes accountability efforts in US-based clinical programs to treat early childhood disruptive behaviors. There are multi-level challenges preventing changes to the prevalent US model of paying a fee for each unit of child mental healthcare, with little regard for patient outcomes. However, opportunities exist to improve US-based accountability efforts; from top-down expansion of financial incentives, accountability initiatives, and PDT evidence-based practices to an iterative, bottom-up development of meaningful outcomes measurement by providers. Greater adoption of outcomes monitoring in US clinical practice for common mental health problems can optimize management of early childhood disruptive behaviors and mitigate long-term societal and economic burdens.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Acri, M., Chacko, A., Gopalan, G., & McKay, M. (2018). Engaging families in treatment for child behavior disorders: A synthesis of the literature. In J. E. Lochman & W. Matthys (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of disruptive and impulse-control disorders (pp. 393–409). Wiley.

American Psychiatric Association, & American Psychiatric Association (APA) (Eds.). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed). American Psychiatric Association.

Armstrong, M. I., Boothroyd, R. A., Rohrer, L., Robst, J., Teague, G., Batsche, C., & Anderson, R. (2016). Access, integration and quality of care for individuals with serious mental health challenges enrolled in Florida’s managed medical assistance program. University of South Florida.

Armstrong, M. I., McCrae, J. S., Graef, M. I., Richards, T., Lambert, D., Bright, C. L., & Sowell, C. (2014). Development and initial findings of an implementation process measure for child welfare system change. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 8(1), 94–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2013.873759

Backer, P. M., Kiser, L. J., Gillham, J. E., & Smith, J. (2015). The Maryland resilience breakthrough series collaborative: A quality improvement initiative for children’s mental health services providers. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 66(8), 778–780. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500036

Baer, D. M., Wolf, M. M., & Risley, T. R. (1987). Some still-current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 20(4), 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1987.20-313

Batty, M. J., Moldavsky, M., Foroushani, P. S., Pass, S., Marriott, M., Sayal, K., & Hollis, C. (2013). Implementing routine outcome measures in child and adolescent mental health services: From present to future practice. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 18(2), 82–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2012.00658.x

Beidas, R., Skriner, L., Adams, D., Wolk, C. B., Stewart, R. E., Becker-Haimes, E., Williams, N., Maddox, B., Rubin, R., Weaver, S., Evans, A., Mandell, D., & Marcus, S. C. (2017). The relationship between consumer, clinician, and organizational characteristics and use of evidence-based and non-evidence-based therapy strategies in a public mental health system. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 99, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2017.08.011

Bickman, L. (2008a). Why don’t we have effective mental health services? Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 35(6), 437–439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-008-0192-9

Bickman, L. (2008b). A Measurement Feedback System (MFS) Is Necessary to Improve Mental Health Outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(10), 1114–1119. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181825af8

Bickman, L. (2012). Why can’t mental health services be more like modern baseball? Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 39(1–2), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-012-0409-9

Boardman, W. K. (1962). Rusty: A brief behavior disorder. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 26, 293–297. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045155

Bonilla, A. G., Pourat, N., Chuang, E., Ettner, S., Zima, B., Chen, X., Lu, C., Hoang, H., Hair, B. Y., Bolton, J., & Sripipatana, A. (2021). Mental health staffing at HRSA-funded health centers may improve access to care. Psychiatric services (Washington, D.C.), 72(9), 1018–1025. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000337

Bourret, J. C., & Pietras, C. J. (2013). Visual analysis in single-case research. In G. J. Madden, W. V. Dube, T. D. Hackenberg, G. P. Hanley, & K. A. Lattal (Eds.), APA handbook of behavior analysis, Vol. 1: Methods and principles (pp. 199–217). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13937-009

Bremer, R. W., Scholle, S. H., Keyser, D., Houtsinger, J. V. K., & Pincus, H. A. (2008). Pay for Performance in Behavioral. Health, 59(12), 11.

Brookman-Frazee, L., Garland, A. F., Taylor, R., & Zoffness, R. (2009). Therapists’ attitudes towards psychotherapeutic strategies in community-based psychotherapy with children with disruptive behavior problems. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 36(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-008-0195-6

Brookman-Frazee, L., Haine, R. A., Baker-Ericzén, M., Zoffness, R., & Garland, A. F. (2010). Factors Associated with Use of Evidence-Based Practice Strategies in Usual Care Youth Psychotherapy. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 37(3), 254–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-009-0244-9

Brookman-Frazee, L., Stadnick, N., Roesch, S., Regan, J., Barnett, M., Bando, L., Innes-Gomberg, D., & Lau, A. (2016). Measuring sustainment of multiple practices fiscally mandated in children’s mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(6), 1009–1022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0731-8

Chorpita, B. F., Daleiden, E. L., Ebesutani, C., Young, J., Becker, K. D., Nakamura, B. J., Phillips, L., Ward, A., Lynch, R., Trent, L., Smith, R. L., Okamura, K., & Starace, N. (2011). Evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: An updated review of indicators of efficacy and effectiveness: EVIDENCE-BASED TREATMENTS FOR CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 18(2), 154–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2011.01247.x

Comer, J. S., Chow, C., Chan, P. T., Cooper-Vince, C., & Wilson, L. A. S. (2013). Psychosocial treatment efficacy for disruptive behavior problems in very young children: A meta-analytic examination. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.10.001

Cook, N. L., Hicks, L. S., O’Malley, A. J., Keegan, T., Guadagnoli, E., & Landon, B. E. (2007). Access to specialty care and medical services in community health centers. Health Affairs, 26(5), 1459–1468. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1459

de Jong, K. (2016). Challenges in the implementation of measurement feedback systems. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(3), 467–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-015-0697-y

Dishion, T. J., Stormshak, E. A., & Kavanagh, K. (2011). Everyday parenting: A professional’s guide to building family management skills (1st ed). Research Press.

Emanuel, R., Catty, J., Anscombe, E., Cantle, A., & Muller, H. (2014). Implementing an aim-based outcome measure in a psychoanalytic child psychotherapy service: Insights, experiences and evidence. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 19(2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104513485081

Eyberg, S. M. (2013). Treating the behaviorally disordered child. In G. P. Koocher, J. C. Norcross, & B. Greene (Eds.), Psychologists’ desk reference (3rd ed., pp. 411–414). Oxford University Press.

Eyberg, S. M., Nelson, M. M., & Boggs, S. R. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 37(1), 215–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410701820117

Fleming, I., Jones, M., Bradley, J., & Wolpert, M. (2016). Learning from a learning collaboration: The CORC approach to combining research, evaluation and practice in child mental health. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(3), 297–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-014-0592-y

Ford, T., Tingay, K., Wolpert, M., & The CORC Steering Group. (2006). CORC’s survey of routine outcome monitoring and national CAMHS dataset developments: A response to Johnston and Gower. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 11(1), 50–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2005.00390.x

Forehand, R., Jones, D. J., & Parent, J. (2013). Behavioral parenting interventions for child disruptive behaviors and anxiety: What’s different and what’s the same. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(1), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.010

Foster, E. M., Jones, D. E., & and The Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2005). The high costs of aggression: Public expenditures resulting from conduct disorder. American Journal of Public Health, 95(10), 1767–1772. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2004.061424

Garland, A. F., Hawley, K. M., Brookman-Frazee, L., & Hurlburt, M. S. (2008). Identifying common elements of evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children’s disruptive behavior problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(5), 505–514. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816765c2

Garland, A. F., Haine-Schlagel, R., Brookman-Frazee, L., Baker-Ericzen, M., Trask, E., & Fawley-King, K. (2013). Improving community-based mental health care for children: Translating knowledge into action. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 40(1), 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-012-0450-8

Goldfine, M. E., Wagner, S. M., Branstetter, S. A., & Mcneil, C. B. (2008). Parent-child interaction therapy: An examination of cost-effectiveness. Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention, 5(1), 119–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0100414

Herschell, A. D., McNeil, C. B., & McNeil, D. W. (2004). Clinical child psychology’s progress in disseminating empirically supported treatments. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 267–288. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bph082

Institute of Medicine (IOM). (2013). Core measurement needs for better care, better health, and lower costs: Counting what counts: Workshop summary. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/18333/core-measurement-needs-for-better-care-better-health-and-lower-costs

James, K., Elgie, S., Adams, J., Henderson, T., & Salkovskis, P. (2015). Session-by-session outcome monitoring in CAMHS: Clinicians’ beliefs. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 8, e26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X15000653

Johnson, C. A., & Katz, R. C. (1973). Using parents as change agents for their children: A review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 14(3), 181–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1973.tb01186.x

Johnston, J. M., & Pennypacker, H. S., Jr. (2009). Strategies and tactics of behavioral research (3rd ed.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Kazdin, A. E. (1997). Parent management training: Evidence, outcomes, and issues. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 1349–1356.

Kelley, S. D., & Bickman, L. (2009). Beyond outcomes monitoring: Measurement feedback systems in child and adolescent clinical practice. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 22(4), 363–368. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e32832c9162

Kim, J. J., Brookman-Frazee, L., Barnett, M. L., Tran, M., Kuckertz, M., Yu, S., & Lau, A. S. (2020). How community therapists describe adapting evidence-based practices in sessions for youth: Augmenting to improve fit and reach. The Journal of Community Psychology, 48(4), 1238–1257. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22333

Kotte, A., Hill, K. A., Mah, A. C., Korathu-Larson, P. A., Au, J. R., Izmirian, S., Keir, S. S., Nakamura, B. J., & Higa-McMillan, C. K. (2016). Facilitators and barriers of implementing a measurement feedback system in public youth mental health. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(6), 861–878. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0729-2

Lambert, M. J., Harmon, C., Slade, K., Whipple, J. L., & Hawkins, E. J. (2005). Providing feedback to psychotherapists on their patients’ progress: Clinical results and practice suggestions. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(2), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20113

Lau, A. S., Fung, J. J., Ho, L. Y., Liu, L. L., & Gudiño, O. G. (2011). Parent training with high-risk immigrant Chinese families: A pilot group randomized trial yielding practice-based evidence. Behavior Therapy, 42(3), 413–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2010.11.001

Lavigne, J. V., Bryant, F. B., Hopkins, J., & Gouze, K. R. (2014). Dimensions of oppositional defiant disorder in young children: Model comparisons, gender and longitudinal invariance. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(3), 423–439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9919-0

Liu, F. F., Cruz, R. A., Rockhill, C. M., & Lyon, A. R. (2019). Mind the gap: Considering disparities in implementing measurement-based care. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(4), 459–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.11.015

Lochman, J. E., Boxmeyer, C., Powell, N., Dillon, C., Powe, C., & Kassing, F. (2017). Disruptive behavior disorders. In C. A. Flessner & J. C. Piacentini (Eds.), Clinical handbook of psychological disorders in children and adolescents: A step-by-step treatment manual (1st ed., pp. 299–328). The Guilford Press.

Lyon, A. R., Dorsey, S., Pullmann, M., Silbaugh-Cowdin, J., & Berliner, L. (2015). Clinician use of standardized assessments following a common elements psychotherapy training and consultation program. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-014-0543-7

Lyon, A. R., Pullmann, M. D., Walker, S. C., & D’Angelo, G. (2017). Community-sourced intervention programs: Review of submissions in response to a statewide call for “Promising practices.” Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(1), 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-015-0650-0

Lyons, J. S., Terry, P., Martinovich, Z., Peterson, J., & Bouska, B. (2001). Outcome trajectories for adolescents in residential treatment: A statewide evaluation. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 10(3), 333–345. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012576826136

Lyons, J. S., Weiner, D. A., & Lyons, M. B. (2004). Measurement as communication in outcomes management: The Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths (CANS). In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (3rd ed., pp. 461–476). Routledge.

Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). (2021). Key federal program accountability requirements in Medicaid managed care. https://www.macpac.gov/subtopic/key-federal-program-accountability-requirements-in-medicaid-managed-care/

Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). (2020). Quality rating systems in Medicaid managed care. https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Quality-Rating-Systems-in-Medicaid-Managed-Care.pdf

Michelson, D., Davenport, C., Dretzke, J., Barlow, J., & Day, C. (2013). Do evidence-based interventions work when tested in the “real world?” A systematic review and meta-analysis of parent management training for the treatment of child disruptive behavior. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 16(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-013-0128-0

Milette-Winfree, M., Nakamura, B. J., Kotte, A., & Higa-McMillan, C. (2019). Multilevel predictors of case managers’ assessment administration behavior in a precursor to a measurement feedback system. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 46(5), 636–648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-00941-2

Norman, S., Dean, S., Hansford, L., & Ford, T. (2014). Clinical practitioner’s attitudes towards the use of Routine Outcome Monitoring within Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services: A qualitative study of two Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 19(4), 576–595. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104513492348

Orimoto, T. E., Mueller, C. W., Hayashi, K., & Nakamura, B. J. (2014). Community-based treatment for youth with co- and multimorbid disruptive behavior disorders. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(2), 262–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-012-0464-2

Post, R. M., Rowe, M., Kaplan, D., & Findling, R. (2017). The child network for parents to track their child’s mood and behavior. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 27(9), 840–843. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2017.0002

Pourat, N., Chen, X., Tsugawa, Y., Lu, C., Zhou, W., Hoang, H., Hair, B., Bolton, J., & Sripipatana, A. (2021). Intersection of complexity and high utilization among health center patients aged 18 to 64 years. The American Journal of Managed Care, 28(2). https://www.ajmc.com/view/intersection-of-complexity-and-high-utilization-among-health-center-patients-aged-18-to-64-years

Reyno, S. M., & McGrath, P. J. (2006). Predictors of parent training efficacy for child externalizing behavior problems—A meta-analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(1), 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01544.x

Sale, R., Bearman, S. K., Woo, R., & Baker, N. (2020). Introducing a measurement feedback system for youth mental health: Predictors and impact of implementation in a community agency. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-020-01076-5

Scott, K., & Lewis, C. C. (2015). Using measurement-based care to enhance any treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.01.010

Scott, S., Knapp, M., Henderson, J., & Maughan, B. (2001). Financial cost of social exclusion: Follow up study of antisocial children into adulthood. British Medical Journal, 323(7306), 191–194.

Seidman, E., Chorpita, B. F., Reay, W. E., Stelk, W., Garland, A. F., Kutash, K., Mullican, C., & Ringeisen, H. (2010). A framework for measurement feedback to improve decision-making in mental health. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 37(1–2), 128–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-009-0260-9

Sheldrick, R. C., Merchant, S., & Perrin, E. C. (2011). Identification of developmental-behavioral problems in primary care: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 128(2), 356–363. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-3261

Shevlin, M., McElroy, E., & Murphy, J. (2017). Homotypic and heterotypic psychopathological continuity: A child cohort study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(9), 1135–1145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1396-7

Southam-Gerow, M. A., Rodríguez, A., Chorpita, B. F., & Daleiden, E. L. (2012). Dissemination and implementation of evidence based treatments for youth: Challenges and recommendations. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(5), 527–534. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029101

Steiner, H., & Remsing, L. (2007). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with oppositional defiant disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(1), 126–141. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000246060.62706.af

Stewart, R. E., Lareef, I., Hadley, T. R., & Mandell, D. S. (2017). Can we pay for performance in behavioral health care? Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 68(2), 109–111. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201600475

Taylor, M. J., McNicholas, C., Nicolay, C., Darzi, A., Bell, D., & Reed, J. E. (2013). Systematic review of the application of the plan–do–study–act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Quality & Safety, 23(4), 290–298. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001862

Tsai, K. H., Moskowitz, A. L., Brown, T. E., Park, A. L., & Chorpita, B. F. (2016). Interpreting progress feedback to guide clinical decision-making in children’s mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(2), 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-015-0630-4

van Aar, J., Leijten, P., Orobio de Castro, B., & Overbeek, G. (2017). Sustained, fade-out or sleeper effects? A systematic review and meta-analysis of parenting interventions for disruptive child behavior. Clinical Psychology Review, 51, 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.11.006

van Sonsbeek, M. A., Hutschemaekers, G. G., Veerman, J. W., & Tiemens, B. B. (2014). Effective components of feedback from Routine Outcome Monitoring (ROM) in youth mental health care: Study protocol of a three-arm parallel-group randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-3

van Sonsbeek, M. A. M. S., Hutschemaekers, G. J. M., Veerman, J. W., Vermulst, A., Kleinjan, M., & Tiemens, B. G. (2020). Challenges in investigating the effective components of feedback from routine outcome monitoring (ROM) in youth mental health care. Child & Youth Care Forum. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-020-09574-1

Vanselow, N. R., Thompson, R., & Karsina, A. (2011). Data-based decision making: The impact of data variability, training, and context. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44(4), 767–780. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2011.44-767

Vermeij, B. A. M., Wiefferink, C. H., Knoors, H., & Scholte, R. (2019). Association of language, behavior, and parental stress in young children with a language disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 85, 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2018.11.012

Vollmer, T. R., Sloman, K. N., & Pipkin, C. S. P. (2008). Practical implications of data reliability and treatment integrity monitoring. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 1(2), 4–11.

Waldron, S. M., Loades, M. E., & Rogers, L. (2018). Routine outcome monitoring in CAMHS: How can we enable implementation in practice? Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 23(4), 328–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12260

Weisz, J. R., & Gray, J. S. (2008). Evidence-based psychotherapy for children and adolescents: Data from the present and a model for the future. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 13(2), 54–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2007.00475.x

Wertz, J., Agnew-Blais, J., Caspi, A., Danese, A., Fisher, H. L., Goldman-Mellor, S., Moffitt, T. E., & Arseneault, L. (2018). From childhood conduct problems to poor functioning at age 18 years: Examining explanations in a longitudinal cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(1), 54-60.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.09.437

Whipple, J. L., & Lambert, M. J. (2011). Outcome Measures for Practice. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7(1), 87–111. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-040510-143938

Wolpert, M., Fugard, A. J. B., Deighton, J., & Görzig, A. (2012). Routine outcomes monitoring as part of children and young people’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (CYP IAPT)—Improving care or unhelpful burden? Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 17(3), 129–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2012.00676.x

Yu-Lefler, H. F., Lindauer, S., & Riley, A. W. (2022). Clinician-identified factors in success of parent-directed behavioral therapy for children’s tantrums. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 49, 168–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-021-01155-1

Yu-Lefler, H., Riley, A. W., Wakeman, J., Rolinec, C., Clark, K. C., Crockett, J. C., Perkins-Parks, S., Richman, G., Lynne, S., Majszak, H., & Cataldo, M. F. (2019). A clinical outcomes system to track treatment progress and promote care accountability in outpatient pediatric behavioral healthcare. Poster of the 2019 annual meeting of the American Public Health Association (APHA), Philadelphia, PA.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Study selection and data extraction was initially performed by HYL. JM and AWR independently reviewed and assisted in finalizing selection and extraction results. The first draft of the manuscript was written by HYL and all authors contributed to subsequent versions of the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This is a scoping review of published, peer-reviewed literature. The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board determined the study as Not Human Subjects Research and exempt from review. All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was not applicable to this study, as individual participants were not consulted as part of the scoping review process.

Standards of Reporting

This manuscript was prepared using the PRISMA Scoping Review guidelines for literature reviews.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Data Abstraction Form

Data | Data details | Data source |

|---|---|---|

Title | – | Database |

Author(s) | – | Database |

Publication date and year | Epub if available | Database |

Publication type | (1) Book chapter/editorial/commentary, (2) review article, (3) empirical article | Database and abstract |

Description | Focus or topic area as it relates to outcomes accountability systems | Abstract and full-text review |

Focus area(s)—plan, do, study, adjust | “Plan” publications provide theoretical basis or best practice suggestions to the building or implementation of outcomes accountability systems. “Do” publications focus on implementation of outcomes accountability systems. “Study” publications either evaluate the impact of outcomes accountability systems on treatment outcomes or utilizes accountability data to determine outcomes. “Adjust” publications focus on factors influencing outcomes and accountability practices, and provides performance improvement suggestions | Full-text review |

Country | Origin of the outcomes accountability system(s) being discussed | Abstract and full-text review |

Setting | Setting of the mental health program and the outcomes accountability system | Abstract and full-text review |

Target patient population(s) | General age groupings (i.e., adult, adolescent, children), clinical presentation, and if there was specific focus on early childhood patients | Full-text review |

Review type—if publication Type = “2” | Critical review, scoping review, literature review, systematic review, meta-analysis | Full-text review |

Study design—if publication Type = “3” | Qualitative, quantitative, or mix-methods. If quantitative or mix-methods, further details on methods used | Full-text review |

Key findings | Summarize publication’s main conclusions and key insights | Full-text review |

Strengths and limitations | How does this publication strengthen or highlight gaps in knowledge regarding outcomes accountability systems for early childhood disruptive behaviors? | Full-text review |

Appendix 2: Detailed Summary of Empirical and Review Articles [in Alphabetical Order by Author]

Authors (year) | Study design/review type | Description | Setting | Key findings | Strengths and limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Empirical articles | |||||

Batty et al. (2013) | Qualitative: notes audit, survey, and interview | Assessed the usage of ROM data in clinical care by CAMHS clinicians Outcome measures used were the HoNOSCA, SDQ, C-GAS, Conner’s rating scales, and CHI-ESQ | CAMHS clinical services in 3 East Midland counties in the UK | Measures inconsistently collected and used, with < 20% of patients with baseline and follow-up data. Issues include lack of clinician confidence in measures to meaningfully measure progress, training support for clinical staff to use ROM in practice, and leadership support to integrate ROM data into practice | Strengths Similar qualitative findings to other studies on integrating outcomes accountability systems into practice and suggest generalizability across children’s mental health care settings Limitations ROM within this study does not specifically focus on treatment for early childhood patients or disruptive behaviors |

Emanuel et al. (2014) | Qualitative: case studies | Assessed clinical feasibility of a patient family-generated, goal-based outcome measure for ROM in treating behavioral problems in children and adolescents | CAMHS outpatient clinic in London providing child therapy and parenting strategies | Results illustrate findings for early childhood cases with disruptive behaviors, which indicated such outcome measures may be more meaningful to patients and their family than standardized assessments, and encourage parental treatment engagement and tracking of their child’s progress | Strengths Provides insight into measures that may be most meaningful to ROM for early childhood disruptive behaviors, particularly for treatment models with parental involvement Limitations Results based on specific patient cases from one clinic |

James et al. (2015) | Mixed methods: cross-sectional association of themes from focus groups and surveys with clinician usage of routine outcomes monitoring | Assessed the usage of session-by-session ROM in CAMHS clinical services and clinician attitudes Outcome measure used was the CYP-IAPT questionnaire | CAMHS clinical services in South West region of the UK | < 7% of clinicians report monitoring outcomes every session. Clinicians who perceived the outcomes data as useful to helping their patients were more likely to engage in session-by-session ROM | Strengths Similar qualitative findings to other studies on integrating outcomes accountability systems into practice and suggest generalizability across children’s mental health care settings Limitations ROM within this study does not specifically focus on treatment for early childhood patients or disruptive behaviors |

Kotte et al. (2016) | Qualitative: key informant interviews | Assessed facilitators and barriers identified by care coordinators to implement and sustain a statewide MFS Outcome measure used was the Ohio Scales | 8 US public mental health system family guidance centers in HI | Factors for success included clinicians’ and patient families’ perceived value in data-driven care and the outcome assessment to meaningfully measure progress; and confidence in leadership to meaningfully integrate the MFS into practice, such as providing adequate data security, training and supervision for clinicians, and dedicated clinical time to track data | Strengths Similar qualitative findings to other studies on integrating outcomes accountability systems into practice and suggest generalizability across children’s mental health care settings Limitations MFS within this study does not specifically focus on treatment for early childhood patients or disruptive behaviors |

Lyon et al. (2015) | Qualitative: survey | Assessed clinician attitudes and usage of standardized assessments for outcomes monitoring at different stages of a statewide training and consultation program for common elements psychotherapy (CBT+) Outcome measures used were the Pediatric Symptom Checklist, Mood and Feelings Questionnaire, SCARED, and CPSS | US public mental health clinics in WA | Support towards using standardized assessments for outcomes monitoring increased from pre- to post-training, with increased usage in later training stages. Clinicians recommended supports to sustain usage, such as integration into an MFS with reminders, and support from clinical leadership to integrate assessment and MFS usage into clinician training, supervision, and practice | Strengths Similar qualitative findings to other studies on integrating outcomes accountability systems into practice and suggest generalizability across children’s mental health care settings Limitations CBT+ program and participating clinicians within this study do not specifically focus on treatment for early childhood patients or disruptive behaviors |

Lyon et al. (2017) | Qualitative: survey | Assessed the prevalence of ROM usage for quality assurance within state-level youth service delivery systems. Information derived from surveying programs listed in the Washington State Evidence-Based Practice Inventory | US public service programs for children in WA | Half of programs use an ROM system for quality assurance purposes and train staff to track and use outcome measures. Programs with high quality ROM practices often reported having a greater evidence base for their practices | Strengths Indicates promising state-level efforts to integrate outcomes accountability systems and practices into programs addressing children’s mental health Limitations Selection bias (programs lacking quality and accountability controls are not listed in the Inventory). Programs do not specifically focus on early childhood patients or disruptive behaviors |

Milette-Winfree et al. (2019) | Mixed methods: cross-sectional association of case manager characteristics from surveys with consistency administering outcomes assessment | Assessed factors associated with case manager’s ability to administer the Ohio Scales to inform MFS implementation feasibility | US-HI Department of Health | Consistent administration of the Ohio Scales is associated with better management of children’s mental health problems. Case managers who reported lower burnout, longer work experience, and having patient caseloads that are lighter and have younger youth with less complex clinical profiles are more able to consistently administer the Ohio Scales | Strengths Indicates promising state-level efforts to integrate outcomes accountability practices into programs addressing children’s mental health. Findings imply Ohio Scales may be an applicable outcomes assessment for early childhood populations Limitations MFS within this study does not specifically focus on clinical treatment for early childhood patients or disruptive behaviors |

Norman et al. (2014) | Qualitative: key informant interviews | Assessed CAMHS clinician attitudes towards ROM | 2 urban CAMHS clinical service sites for severe and common mental health problems | Attitudes were generally neutral. Advantages were usefulness in setting treatment goals, monitoring progress, and comparing effect across treatment programs. Barriers were lack of confidence in standardized assessments to meaningfully measure progress; lack of leadership support, training, and dedicated clinical time to integrate ROM data into practice; and ethical concern of how ROM data is being used by leadership or policymakers to determine care effectiveness and value | Strengths Similar qualitative findings to other studies on integrating outcomes accountability systems into practice and suggest generalizability across children’s mental health care settings Limitations ROM within this study does not specifically focus on treatment for early childhood patients or disruptive behaviors |

Sale et al. (2020) | Quantitative: observational, prospective study | Assessed influence of MFS usage on clinical symptom reduction, and factors associated with MFS usage Outcome measure used was the Y-OQ | US private, community-based outpatient mental health center in TX with most patients on Medicaid or subsidized insurance | Higher MFS usage was associated with faster symptom reduction. Patients assigned to less experienced clinicians had greater MFS usage than patients assigned to more experienced staff | Strengths Provides insight into how MFS usage influences clinical outcomes, and factors associated with its usage in practice Limitations MFS within this study does not specifically focus on treatment for early childhood patients or disruptive behaviors (patients averaged 10–11 years old, and had various mental health problems). Unknown generalizability to patients of higher socioeconomic status |

Tsai et al. (2016) | Quantitative: observational, retrospective study | Assessed the amount of ROM datapoints needed to predict progress in patient symptomology and inform clinical decision-making Outcome measure used was the BPC | 3 US public mental health programs in Los Angeles County | At least 11 weekly datapoints are needed to accurately predict outcomes 20 weeks from beginning of treatment, with diminishing returns if more data is collected | Strengths Provides insight into the amount of ROM data needed to provide meaningful feedback Limitations ROM within this study does not specifically focus on treatment for early childhood patients or disruptive behaviors |

Van Sonsbeek et al., (2014, 2020) 2014: study proposal 2020: study results | Quantitative: clustered RCT by child age and location | Assessed treatment effect for common mental health problems when clinicians receive (1) ROM data only, (2) ROM data with electronic decision support, (3) ROM data with electronic decision support and colleague case consultation Outcome measures used were the SDQ and KIDSCREEN | Outpatient psychiatric centers of a private mental health institution in the Netherlands | Results indicated no significant differences found among the different ROM feedback conditions. However, ~ 80% of the study population was excluded from analysis due to infrequent outcomes data collection, and there was poor adherence to feedback protocols in each ROM condition | Strengths Data provides insight on the effect of ROM feedback conditions on clinical outcomes Limitations Results were based on a small portion of the original study population, and ROM conditions had questionable implementation fidelity. Dataset does not adequately represent early childhood patients or disruptive behaviors (youngest age group averaged 12 years old with various mental health problems) |

Vermeij et al. (2019) | Quantitative: observational, cross-sectional retrospective study | Used ROM data to assess the association of behavior problems and language skills by type of language disorder and level of parental stress Measures used were SRLT, PPVT-III-NL, SELT (language skills); CBCL, C-TRF (behavior); and PSQ (parental stress) | Specialty outpatient clinic for early language intervention in the Netherlands | Better receptive skills were associated with lower behavior problems, while better expressive skills were associated with higher levels of behavior problems. Parental stress and type of language disorder did not change the association between behavior problems and language skills | Strengths Provides an example on the application of ROM data to assess factors influencing outcomes in an early childhood clinical population Limitations Study focuses on language skills and not behavioral problems as the outcome of interest. Results may have limited generalizability to early childhood populations without language disorders |

Waldron et al. (2018) | Mixed methods: cross-sectional association of themes from focus groups and surveys with clinician usage of routine outcomes monitoring | Assessed the experiences of an “enforced” implemented CYP-IAPT program and associated ROM on clinicians across different specialties and experience levels | Urban CAMHS clinical services in the UK | Clinician usage of ROM increased 6 months post-implementation. Clinicians who perceived the outcomes data as useful to helping their patients were more likely to use ROM. Barriers were lack of confidence in standardized assessments to meaningfully measure progress; lack of leadership support, training, and dedicated clinical time to integrate ROM data into practice; and ethical concern of how ROM data is being used by leadership or policymakers to determine care effectiveness and value | Strengths ROM usage shown to improve over time. Similar qualitative findings to other studies on integrating outcomes accountability systems into practice and suggest generalizability across children’s mental health care settings Limitations Only 33% of eligible clinicians participated in the study. ROM within this study does not specifically focus on treatment for early childhood patients or disruptive behaviors |

Review articles | |||||

Fleming et al. (2016) | Critical review | Discussed lessons learned from CORC, a learning collaborative focused on using ROM to improve service provision and treatment for children with mental health issues and their families | CAMHS clinical services in the UK | CORC helped implement procedures in CAMHS clinics to routinely collect outcome measures for service evaluation and research. Current review outlines a self-review and accreditation framework to better support clinician training and usage of ROM data in practice | Strengths Lessons focus on how to better integrate ROMs into practice once they are implemented Limitations Lessons are derived from a healthcare system with coordinated, top-down initiatives to implement ROMs; unknown generalization to clinical settings without such coordinated support. Review does not specifically focus on treatment of early childhood patients or disruptive behaviors |

Garland et al. (2013) | Critical review | Discussed a multi-level framework to improve assessment and practice of children’s routine mental healthcare by increasing (a) service access and engagement, (b) delivery of evidence-based practices, and (c) outcomes accountability at the patient/family, clinician, provider organization, and policy levels | Children’s mental healthcare in the US | Framework suggests following to improve outcomes accountability: increase policy and payment incentives, assist organizations to build meaningful MFS infrastructure and provide dedicated time and training for clinicians to collect and use outcomes data in practice, and educate patient families on differential quality in providers and value of outcomes monitoring | Strengths Describes actions needed at different service levels to support sustainable integration of outcome monitoring within US children’s mental healthcare clinical practices Limitations Proposal only; policy-making inertia to create outcomes accountability incentives for mental healthcare and providers’ lack of trust and value on outcome assessments, are challenges to translating the framework into action. Review does not specifically focus on treatment of early childhood patients or disruptive behaviors |

Kelley and Bickman (2009) | Literature review | Discussed challenges integrating evidence-based assessments for outcomes monitoring and outcomes monitoring overall into routine practice in US children’s mental healthcare | Children’s mental healthcare in the US | Assessments, particularly those providing multi-dimensional feedback on progress and success, enhance clinical care and outcomes. However, providers distrust and inconsistently use assessments for outcomes monitoring. National, top-down policy incentives are needed for better integration | Strengths Highlights barriers in integrating outcomes monitoring practices into US children’s mental healthcare Limitations Proposal only; unknown when or if the suggestions will be translated into action. Review does not specifically focus on treatment of early childhood patients or disruptive behaviors |

Seidman et al. (2010) | Critical review | Discussed a multi-level MFS based on Bickman’s (2008a, 2008b) design to improve prevention of children’s mental health problems and promote well-being | Universally-applicable, but targeting children’s mental healthcare in the US | Meaningful outcome measures can differ at the patient–clinician, organizational, and policy level. A multi-level MFS better supports meaningful outcomes measurement and feedback at each level | Strengths Provides suggestions on how to make outcomes monitoring more meaningful, and thereby more integrated, into different levels of US children’s mental healthcare Limitations Theoretical in nature; unknown how practical it is to implement the framework in actual practice. Review does not specifically focus on treatment of early childhood patients or disruptive behaviors |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yu-Lefler, H.F., Marsteller, J. & Riley, A.W. Outcomes Accountability Systems for Early Childhood Disruptive Behaviors: A Scoping Review of Availability. Adm Policy Ment Health 49, 735–756 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-022-01196-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-022-01196-0