Abstract

Anal fissure is one of the most common and painful proctologic diseases. Its treatment has long been discussed and several different therapeutic options have been proposed. In the last decades, the understanding of its pathophysiology has led to a progressive reduction of invasive and potentially invalidating treatments in favor of conservative treatment based on anal sphincter muscle relaxation. Despite some systematic reviews and an American position statement, there is ongoing debate about the best treatment for anal fissure. This review is aimed at identifying the best treatment option drawing on evidence-based medicine and on the expert advice of 6 colorectal surgeons with extensive experience in this field in order to produce an Italian position statement for anal fissures. While there is little chance of a cure with conservative behavioral therapy, medical treatment with calcium channel blockers, diltiazem and nifepidine or glyceryl trinitrate, had a considerable success rate ranging from 50 to 90%. Use of 0.4% glyceryl trinitrate in standardized fashion seems to have the best results despite a higher percentage of headache, while the use of botulinum toxin had inconsistent results. Nonresponding patients should undergo lateral internal sphincterotomy. The risk of incontinence after this procedure seems to have been overemphasized in the past. Only a carefully selected group of patients, without anal hypertonia, could benefit from anoplasty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anal fissure is one of the most frequent and painful anal diseases and its clinical management is still controversial despite several systematic reviews. Therefore, the aim of this paper was to establish a position paper on fissure management based on the currently available literature and discussion among a group of Italian experts on this topic.

Definitions, epidemiology, and etiology

The commonly accepted definition of anal fissure is: “A linear ulcer of the anoderm, distal to the dentate line, generally located in the posterior midline” [1–4].

Anal fissure is very painful, because it affects the multilayer squamous epithelium of the anoderm, which is richly innervated with pain fibers. During defecation, the lesion is stretched with consequent painful symptomatology, which can persist for a certain amount of time [5] and be accompanied by slight bleeding. The pain can be so intense as to induce the patient to avoid defecation with consequent hardening of the feces and exacerbation of the problem [1, 6].

Anal fissures are considered to be acute if they have been present for less than 6 weeks, superficial, and have well-demarcated edges. They are considered chronic, instead, if they have been present for more than 6 weeks and have keratinous edges, if there is a sentinel node and hypertrophied anal papillae and if the fibers of the internal anal sphincter are visible [1, 6–8].

Primary anal fissures are not caused by underlying chronic disease whereas secondary anal fissures are associated with other diseases, such as chronic inflammatory intestinal diseases, human immunodeficiency virus tuberculosis, syphilis, and some neoplasms.

Primary anal fissures are most frequent in young adults of both sexes [9].

In 80–90% of the cases, they are located in the posterior midline [4, 5, 9], and more rarely in the anterior region. Associated pathologies should be suspected if there are anal fissures in other regions than the posterior region [1, 4, 10]. Anterior lesions are more frequent in women than in men [5, 11].

Anal fissures are not common in patients older than 65 years, and in this age group must be suspected to be associated with other pathologies [6]. Data are not available on its prevalence in the general population. The lifetime incidence is calculated to be 11% [12].

In Italy anal fissures represent the second most common cause of a proctology specialist visit after hemorrhoidal pathology. In England, in the period 2005–2006, the incidence of hospitalization for anal fissure was calculated to be 1.56 per 10,000 inhabitants [13]. According to the data of the 2009 Annual Report prepared by the SICCR (Italian Society of Colorectal Surgery), in 2009, a total of 5,199 patients were observed for anal fissure at Italian coloproctology centers, 1924 (37%) of whom underwent surgery [14].

Etiology

There has been much debate about the causes of primary anal fissures. Historically, the eliciting factor was considered to be the trauma resulting from the passage of hard feces [15], but less than 25% of the cases of chronic anal fissures are associated with constipation [1, 9, 12]. Furthermore, many anal fissures of traumatic origin heal whereas others do not. For many years an association with internal anal sphincter (IAS) hypertonia has been evident [16, 17], although in elderly patients [18, 19] and in postpartum patients [20] cases of anal fissure have been reported that are associated with a normal or hypotonic IAS.

The basal tone of the IAS is affected by various substances, including nitric oxide (NO) [21]. In patients with anal fissures, the synthesis of NO in the IAS is reduced in comparison with the controls [22]. Manometry studies have demonstrated an increased IAS tone and a reduction in anodermal vascular blood flow, mainly in the posterior region [23, 24] and showed that in patients who benefited from sphincterotomy surgery or from anal stretch sphincter hypertonia was reduced and blood flow increased. This pathogenetic mechanism can explain the achievement of a high rate of healing with medical therapies able to improve blood flow [25] and/or to reduce hypertonia [6].

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on the presence of intense pain, with possible bleeding, during or after defecation and is confirmed by a careful inspection of the posterior commissure of the anus. The following are the pain characteristics of anal fissure: intense burning pain that appears immediately or later after evacuation of the bowels, of variable duration, described as passing a “razor blade” or “broken glass” [1–4].

The majority of anal fissures are visible upon simple divarication of the glutei and during straining [9], at the level of the posterior commissure (80–90%) or the anterior commissure (10%) or more rarely the anteroposterior commissure and in these cases digital exploration can be avoided [26]. In some cases, the lesion can be identified only through the use of an anoscope.

Spasm and pain can make diagnosis impossible [1]. Therefore, exploration under anesthesia is sometimes indispensable.

Upon inspection primary chronic anal fissure presents as wide and deep, with sphincter fibers visible, frequent presence of a sentinel pseudopolyp, hypertrophied anal papillae, and keratinous edges [2, 6–8]. If the diagnosis of primary anal fissure is in doubt, for example in the case of anal fissure in a region other than the posterior region, or in the presence of multiple anal fissures or a painless anal fissure that does not resolved with the therapy, examination under anesthesia with biopsy and appropriate cultures is indispensable [6].

The differential diagnosis includes hemorrhoids [6] and other neoplastic, infective, or chronic inflammatory pathologies in the anal region.

Conservative treatment

Improving diet and defecation habits is a good long-term strategy for reducing gastrointestinal problems.

Therefore, patients with primary chronic anal fissures are advised to assume liquids and fiber supplements as well as bulk-forming emollient laxatives and to use warm sitz baths. The amount of fiber should be increased gradually to avoid problems of flatulence.

These simple measures are able to reduce the pain and should be recommended to all patients. If bulk-forming laxatives are not sufficient, osmotic laxatives can be tried. To reduce the pain, local anesthetics can be used as additional measures but only for short periods of time due to the risk of skin sensitization [2, 10, 27].

It is important to emphasize that, in the case of acute anal fissures, conservative treatment can provide a cure in 87% of the cases, while in chronic forms this figure is 50% [28–30].

Medical therapy

The goal of medical treatment for chronic anal fissure is to achieve a temporary reduction of pressure of the anal canal, to facilitate the healing of the fissure (“reversible sphincterotomy”), thereby reducing muscle tone. Various mechanisms can be used: increasing NO, direct depletion of intracellular calcium, stimulation of muscarinic receptors, inhibition of alpha-adrenergic receptors, or stimulation of beta-adrenergic receptors [1].

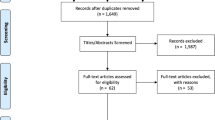

In all of the most recent guidelines topical nitrates and topical calcium channel blockers are included among the pharmacological therapy options [1–3, 6]. From a search of PubMed using the most common keywords associated with this pathology (chronic anal fissures, topical nitrates, topical nifedipine, topical diltiazem), we found 68 trials using glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), 20 trials using diltiazem, and just 5 trials with nifepidine.

Topical nitrates

Since the discovery of the role of NO as an inhibitor of IAS tone [21], the use of nitrates has been shown to reduce anal hypertonia [31] and in many clinical contexts it has become the first-line therapy for chronic anal fissures [7].

The introduction of topical nitrates has had an important impact on the reduction of the number of surgical procedures, especially in several European countries [32].

The first trials that were conducted demonstrated a cure rate of 59–86% [33–36], but without standardization of the doses. A study focusing on the optimal nitroglycerin ointment dose and dosing interval was carried out by Bailey and colleagues [36].

Glyceryl trinitrate has been tested mainly in two formulations: 0.2 and 0.4%.

0.2% GTN

Randomized controlled trials conducted with 0.2% GTN ointment had cure rates of between 50 and 68% [37, 38].

A recent Cochrane review of the medical therapy for anal fissures demonstrates that as regards the cure rate topical nitrates are marginally but significantly superior to placebo [39]. It is important to note the significant effect these drugs had on reducing pain [35–37], and the positive effect on the patient’s well-being, physical activity, and vitality, the fundamental components of quality of life [40].

The percentage of recurrence in some patients after therapy ended was correlated with regaining hypertonia [41]. A review by Nelson [42] reports a recurrence rate of approximately 50%.

The most common adverse event correlated with topical nitrates therapy is transitory headache reported in an average of 25% of the patients and easily manageable with a therapy based on mild pain relievers [42]. Although frequent, the development of headache does not lead to reduced compliance. In fact, as some clinical experiences demonstrate, for the patient the pain associated with anal fissure is decidedly more serious than that caused by the headache, and therefore interruption of therapy due to this adverse event is rare [39, 43].

In any case, the headache can easily be managed by informing the patient that it may occur and that it can be kept under control by means of a suitable pharmacological therapy or with some simple techniques, such as, for example, beginning the therapy with lower doses than the therapeutic doses, to reach the recommended dosage regimen within 4–5 days.

0.4% GTN

Recently an ointment containing 0.4% GTN has been industrially manufactured.

A recent trial conducted in Italy on patients affected by chronic anal fissures treated with an industrially manufactured ointment containing 0.4% GTN demonstrated a clinical cure in 54% of the patients. Pain symptoms, measured by means of the visual analog scale (VAS), disappeared in 62% of the patients. Furthermore, a correlation was demonstrated between pain reduction and improvement in all of the components of quality of life (activity, anxiety/depression) [44].

An analysis presented by Sands in 2005 [45] compared the results of treatment with 0.4% GTN versus placebo and 0.2% GTN versus placebo. A significant reduction in anal pain caused by GTN in comparison with placebo was demonstrated only in the first group of patients.

Treatment with 0.4% GTN achieved this result in a shorter amount of time (6 days vs. 18 days) than treatment with 0.2% GTN.

In the same trial, the tolerability profile was similar in the two groups and comparable to the groups reported in the literature, with episodes of transitory headache that did not prevent 90% of the patients with this symptom from completing therapy.

Calcium channel blockers

The calcium channel blockers reduce muscle tone. Currently, only two industrial preparations based on the channel blockers nifedipine and diltiazem exist on the market in a topical form. Only the former is available in Italy, while the latter is available in the UK and in the United States.

Diltiazem

Two percent diltiazem was used in several clinical experiences, obtaining a cure in 75% of the patients. The doses used varied greatly among the trials [10], almost all of which were conducted without comparison of diltiazem to placebo, with a length of therapy sometimes greater than 8 weeks [46], and with limited patient case histories [47].

The use of diltiazem has been associated with the development of migraine and pruritus ani [48].

Recurrence is also a problem for this class of drug. In one of the few long-term trials [49], more than 60% of the patients experienced recurrence within 2 years after the end of therapy.

Nifedipine

Regarding nifedipine, there have been very few trials conducted with the drug at different concentrations in the Mediterranean area (Italy, Turkey, Greece, and Israel).

In Italy, an industrially manufactured ointment with a formulation of 0.3% nifedipine +1.5% lidocaine is available. With this preparation was published a single double-blind, randomized, prospective trial on 110 patients with chronic anal fissures (55 treated with nifedipine + 1.5% lidocaine and 55 treated with 1% hydrocortisone + 1.5% lidocaine). The reported cure rate after 6 weeks of treatment was 95% compared to 16% of the control group, without any systemic adverse reaction in the group treated with nifedipine + lidocaine [50]. This trial, the results of which are not in line with the international literature on medical therapy for anal fissures and have not yet been confirmed by other authors, presents important limits, including the use of cortisone, which could have blocked the healing process of fissures in the control group [51].

Duration of therapy

In the literature, therapy is administered for at least 6–8 weeks. A reduction in pain generally occurs within 2 weeks from the beginning of therapy.

Recent work by Gagliardi and colleagues [44] conducted with 0.4% GTN demonstrated that pain during evacuation, measured by means of the VAS scale, improves significantly after 2, 4, and 6 weeks of treatment, while the extension of therapy up to 12 weeks does not yield any further benefits.

Furthermore, this trial demonstrated a significant improvement in quality of life, which was already appreciable after 14 days, with continuous improvement up until the end of treatment.

In the Phase III clinical trials conducted by Sands, pain relief was achieved more quickly with the 0.4% ointment than with the 0.2% ointment (6 days vs. 18 days).

Also, in the only trial reported with nifedipine + lidocaine, the duration of the treatment for chronic anal fissures was 6 weeks [50].

The Clinical Knowledge Summaries [3] indicate topical nitrates as the first line of pharmacological treatment together with conservative therapy, and they recommend the continuation of treatment for at least 6–8 weeks, suggesting, in cases of persistent anal fissures, further cycles of medical therapy before considering surgery.

Comparison of pharmacological therapies

The Cochrane review [42], which considered only those trials conducted with galenic formulations of 0.2% GTN versus calcium channel blockers, concludes that it is not possible to demonstrate any significant differences with regard to the cure rate, in part because of the scarcity of comparative trials. However, in a double-blind, randomized, prospective trial [52] that compared 0.2% GTN and topical calcium channel blockers, the percentages of recurrence were found to be significantly higher in the group treated with calcium channel blockers (42% vs. 31%), while the results regarding reduction of pain were found to be virtually identical. Instead, no direct comparisons exist between ointment containing 0.4% GTN and topical calcium channel blockers.

Botulinum toxin

The proposal to use botulinum toxin, based on its possible reduction of internal anal sphincter tone, faces some difficulties in daily clinical practice in connection with locating the drug, the nonstandardized dose [53], the injection site that is not well-defined [54, 55], the invasiveness of the method, and the higher cost of treatment [56].

A high percentage of recurrence (40–55% at 3–4 years) [57] and a significant incidence of adverse events such as fecal incontinence (10%) [58, 59], hematomas, and subcutaneous infections [55] are described after treatment with botulinum toxin. Furthermore, there is insufficient data on long-term efficacy.

A randomized trial of topical nitrates versus botulinum toxin showed greater efficacy of the nitrates at 2 weeks (cure rate of 52% vs. 24%, P < 0.05) [60].

Other drugs

Other drugs have been proposed for medical treatment of anal fissures: muscarinic agonists, adrenergic agonists and antagonists, and phosphodiesterase inhibitors.

However, their role still remains to be determined. Local anesthetics such as lidocaine can act as analgesics, like paracetamol and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. [23].

Surgical options

Surgery should be reserved for those cases in which nonsurgical treatments fail. From the most recent trials it appears to be important that medical therapy be extended to at least 6 weeks before it is considered to have failed. The patient must be informed of the risk of fecal incontinence, which should always be discussed when obtaining the informed consent of the patient [2, 7].

Anal stretch, reintroduced into anal fissure therapy in 1964 [61] with significant success rates [62], is, however, associated with recurrence rates varying from 2% to 80% [63, 64], a high risk of incontinence (up to 51%) [65, 66], and is widely criticized despite a reported cure rate of approximately 90% [63].

More recently, an attempt was made to standardize anal dilatation with pressurized balloons (controlled pneumatic dilatation) to reduce the incidence of sphincter injury [67, 68] with appreciable results. In Italian clinical practice, anal dilators are frequently used, although there is very little scientific evidence regarding the benefits of this treatment [69].

Lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS), performed with an open or closed technique, involves an incision of the internal sphincter, more or less extended, distal to the dentate line, with the possible excision of the sentinel node and the hypertrophied papillae [68, 70]. The cure rate after LIS is higher than 90% [71]. Both techniques demonstrate virtually identical efficacy [72–74] and a similar incidence of incontinence, even though in one trial [75] the incidence of soiling after open LIS was significantly higher than after closed LIS [P < 0.001]. Complications include bleeding, hematoma, abscess, and fistulas. Lateral internal sphincterotomy achieves efficacy rates higher than those of nonsurgical therapy, but is associated with an increased risk of minor fecal incontinence after surgery (approx. 10%). Therefore, extreme prudence is recommended in considering LIS for high risk patients, such as the elderly, multiparous women, patients with previous biliopancreatic bypass for obesity, and patients with previous proctologic surgery.

Lateral internal sphincterotomy is superior to fissurectomy and posterior sphincterotomy because it is associated with faster healing, less pain, and less postoperative incontinence [68].

The technique of anoplasty, with or without sphincterotomy, is only considered an alternative to LIS, but there are no randomized comparison trials [76]. It can be indicated in the following situations: sphincter hypotonia or normal tone, previous anal surgery, and diagnostic doubt.

Diathermy coagulation and cryosurgery of anal fissure are nonrecommended procedures.

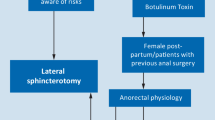

Therapeutic algorithm

In the various therapeutic algorithms proposed [1, 7, 23, 77], nonsurgical, conservative, medical therapy is considered first-line treatment.

In consideration of the note of AIFA, the Italian drug regulatory agency, published in February 2009 in an issue of Reazioni, their official bulletin, which advises against the use of lidocaine-based anesthetics (lidocaine is contained in the formulation of the nifedipine-based ointment) on skin lesions, the panel is of the opinion that the first-line pharmacological therapy for primary chronic anal fissure can be based on the 0.4% GTN ointment, also based on the more extensive international literature that is currently available on GTN.

Should medical therapy fail, open or closed lateral internal sphincterotomy is the surgical option of choice. The use of botulinum toxin and dilatations is not currently considered a suitable treatment. Anoplasty can be performed in the specific cases cited above.

References

Cross KL, Massey EJDA, Fowler AL, Monson JRT (2008) The management of anal fissure: ACPGBI position statement. Colorectal Dis 10(Suppl 3):1–7

Orsay C, Rakinic J, Perry Brian W et al (2004) ASCRS practical parameters for the management of anal fissures. Dis Colon Rectum 47:2003–2007

CKS/NHS Anal fissure, http://www.cks.nhs.uk/anal_fissure#-314748

Lund JN, Scholefield JH (1996) Aetiology and treatment of anal fissure. Br J Surg 83:1335–1344

Goligher JC (1975) Surgery of the anus, Rectum & Colon, 3rd edn. Balliere & Tindall, London

American Gastroenterology Association (AGA) (2003) American gastroenterological association medical position statement: diagnosis and care of patients with anal fissure. Gastroenterology 124:233–234

Collins EE, Lund NJ (2007) A review of chronic anal fissure management. Tech Coloproctol 11:209–223

Lindsey I, Jones OM, Cunningham C, Mortensen NJ (2004) Chronic anal fissure. Br J Surg 91:270–279

Hananel N, Gordon PH (1997) Re-examination of clinical manifestation and response to therapy of fissure-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 40:229–233

Steele SR, Madoff RD (2006) Systematic review: treatment of anal fissure. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 24:247–257

Notaras MJ (1988) Anal fissure and stenosis. Surg Clin North Am 68:1427–1440

Lock MR (1977) Thompson JPS Fissure-in-ano: the initial management and prognosis. Br J Surg 84:86–88

Hospital Episode Statistics (2007) Hospital Episode Statistics 2005/2006. Department of Health. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. www.hesonline.nhs.uk

SICCR Annual Report (2009). www.siccr.org

Ball C (1908) The rectum, its diseases and developmental defects. Hodder and Stoughton, London

Brodie BC (1835) Lectures on diseases of the rectum: preternatural contraction of the sphincter ani. Lond Med Gazette 16:26–31

Hancock BD (1977) The internal sphincter and anal fissure. Br J Surg 64:92–95

Favetta U, Amato A, Interisano A, Pescatori M (1996) Clinical, monometric and sonographic assessment of the anal sphincters. A comparative prospective study. Int J Colorectal Dis 11:163–166

Bove A, Balzano A, Perrotti P, Antropoli C, Lombardi G, Pucciani F (2004) Different anal pressure profiles in patients with anal fissure. Tech Coloproctol 8:151–156

Corby H, Donnelly VS, O’Herlihy C, O’Connell PR (1997) Anal canal pressures are low in women with postpartum anal fissure. Br J Surg 84:86–88

Rattan S, Chakder S (1992) Role of nitric oxide as a mediator of internal anal sphincter relaxation. Am J Physiol 262:G107–G112

Lund J (2006) Nitric oxide deficiency in the internal anal sphincter of patients with chronic anal fissure. Int J Colorectal Dis 21:673–675

Schouten WR, Briel JW, Auwerda JJ (1994) Relationship between anal pressure and anodermal blood flow. Dis Colon Rectum 37:664–669

Schouten WR, Briel JW, Auwerda JJ, De Graaf EJ (1996) Ischaemic nature of anal fissure. Br J Surg 83:63–65

Kua KB, Kocker HM, Kelkar A, Patel AG (2001) Effect of topical glyceryl trinitrate on anodermal blood flow in patients with chronic anal fissures. ANZ J Surg 71:548–550

Jones OM, Ramalligam T, Lindsey I, Cunningham C, George BD, Mortensen NJ (2005) Digital rectal examination of sphincter pressures in chronic anal fissure is unreliable. Dis Colon Rectum 48:349–352

Jensen SL (1986) Treatment of first episodes of acute anal fissure: prospective randomised study of lignocaine ointment versus hydrocortisone ointment or warm sitz baths plus bran. BMJ 292:1167–1169

Jiang JK, Chiu JH, Lin JK (1999) Local thermal stimulation relaxes hypertonic anal sphincter: evidence of somatoanal reflex. Dis Colon Rectum 42:1152–1159

Gough MJ, Lewis A (1983) The conservative treatment of fissure-in-ano. Br J Surg 70:175–176

Jensen SL (1987) Maintenance therapy with unprocessed bran in the prevention of acute anal fissure recurrence. J R Soc Med 80:296–298

Loder PB, Kamm MA, Nicholls RJ, Phillips RK (1984) Reversible chemical sfincterotomy by local application of glyceryl trinitrate. Br J Surg 81:1386–1389

Lund JN, Nystrom PO, Coremans G et al (2006) An evidence-based treatment algorithm for anal fissure. Tech Coloproctol 10:177–180

Gorfine SR (1995) Topical nitroglycerin therapy for anal fissures and ulcers. N Engl J Med 333:1156–1157

Lund JN, Armitage NC, Scholefield JH (1996) Use of glyceryl trinitrate ointment in the treatment of anal fissure. Br J Surg 83:776–777

Kennedy ML, Sowter S, Nguyen H, Lubowski DZ (1999) Glyceryl trinitrate ointment for the treatment of chronic anal fissure: results of a placebo-controlled trial and long-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum 42:1000–1006

Bailey HR, Beck DE, Billingham RP et al (2002) A study to determine the nitroglycerin ointment dose and dosing interval that best promote the healing of chronic anal fissures. Dis Colon Rectum 45:1192–1199

Altomare DF, Rinaldi M, Milito G et al (2000) Glyceryl trinitrate for chronic anal fissure-healing or headache? Results of a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Dis Colon Rectum 43:174–179

Lund JN, Scholefield JH (1997) A randomised, prospective, double blind, placebo-controlled trial of glyceryl trinitrate ointment in treatment of anal fissure [published erratum appears in Lancet 349:656]. Lancet 349:11–14

Nelson R (2004) A systematic review of medical therapy for anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum 47:422–431

Griffin N, Acheson AG, Tung P, Sheard C, Glazebrook C, Scholefield JH (2004) Quality of life in patients with chronic anal fissure. Colorectal Dis 6:39–44

Graziano A, Svidler Lopez L, Lencinas S, Masciagnoli G, Gualdrini U, Bisisio O (2001) Long-term results of topical nitroglycerin in the treatment of chronic anal fissures are disappointing. Tech Coloproctol 5:143–147

Nelson R (2006) Non surgical therapy for anal fissure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 18:CD003431

Fenton C, Wellington K, Easthope SE (2006) 0.4% nitroglycerin ointment in the treatment of chronic anal fissure pain. Drugs 66:343–349

Gagliardi G, Pascariello A, Altomare DF et al (2010) Optimal treatment duration of glyceryl trinitrate for chronic anal fissure: results of a prospective randomized multicenter trial. Tech Coloproctol 14:241–248

Sands LR (2006) 0.4% nitroglycerin ointment in the treatment of chronic anal fissure pain: a viewpoint by Laurence R. Sands. Drugs 66:350–352

Knight JS, Birks M, Farouk R (2001) Topical diltiazem ointment in the treatment of chronic anal fissure. Br J Surg 88:553–556

Carapeti EA, Kamm MA, Phillips RK (2000) Topical diltiazem and bethanechol decrease anal sphincter pressure and heal anal fissures without side effects. Dis Colon Rectum 43:1359–1362

Bielecki K, Kolodziejczak M (2003) A prospective randomized trial of diltiazem and glyceryl trinitrate ointment in the treatment of chronic anal fissure. Colorectal Dis 5:256–257

Nash GF, Kapoor K, Saeb-Parsy K, Kunanandam T, Dawson PM (2006) The long-term results of diltiazem treatment for anal fissure. Int J Clin Pract 60:1411–1413

Perrotti P, Bove A, Antropoli C et al (2002) Topical nifedipine with lidocaine ointment vs. active control for treatment of chronic anal fissure: results of a prospective, randomized, doubleblind study. Dis Colon Rectum 45:1468–1475

Merenstein D, Rosenbaum D (2003) Is topical nifedipine effective for chronic anal fissures? J Fam Pract 52:190–192

Ezri T, Susmallian S (2003) Topical nifedipine vs topical glyceryl trinitrate for treatment of chronic anal fissure. Dis Col Rectum 46:805–808

Jost WH (1997) One hundred cases of anal fissure treated with botulinum toxin: early and long-term results. Dis Colon Rectum 40:1029–1032

Maria G, Brisinda G, Bentivoglio AR, Cassetta A, Gui D, Albanese A (2000) Influence of botulinum toxin site of injections on healing rate in patients with chronic anal fissure. Am J Surg 179:46–50

Minguez M, Melo F, Espi A et al (1999) Therapeutic effects of different doses of botulinum toxin in chronic anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum 42:1016–1021

Essani R, Sarkisyan G, Beart RW, Ault G, Vukasin P, Kaiser AM (2005) Cost-saving effect of treatment algorithm for chronic anal fissure: a prospective analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 9:1237–1244

Arroyo A, Perez F, Serrano P et al (2005) Long-term results of botulinum toxin for the treatment of chronic anal fissure: prospective clinical and manometric study. Int J Colorectal Dis 20:267–271

Brisinda G, Maria G, Sganga G, Bentivoglio AR, Albanese A, Castagneto M (2002) Effectiveness of higher doses of botulinum toxin to induce healing in patients with chronic anal fissures. Surgery 131:179–184

Maria G, Cassetta E, Gui D, Brisinda G, Bentivoglio AR, Albanese A (1998) A comparison of botulinum toxin and saline for the treatment of chronic anal fissure. N Engl J Med 338:217–220

Fruehauf H, Fried M, Wegmueller B, Bauerfeind P, Thumshirn M (2006) Efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin compared with topical nytroglycerin oinment for the treatment of chronic anal fissure: a prospective randomized study. Am J Gastroenterol 101:2107–2112

Watts JM, Bennett RC, Goligher JC (1964) Streching of anal sphincters in treatment of fissure-in-ano. Br Med J 2:342–343

Sohn N, Eisenberg MM, Weinstein MA, Lugo RN, Ader J (1992) Precise anorectal sphincter dilatation-its role in the therapy of anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum 35:322–327

Marby M, Alexander-Williams J, Buchmann P et al (1979) A randomized controlled trial to compare anal dilatation with lateral subcutaneous sphincterotomy for anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum 22:308–311

Jensen SL, Lund F, Nielsen OV, Tange G (1984) Lateral subcutaneous sphincterotomy versus anal dilatation in the treatment of fissure in ano in outpatients. A prospective randomized study. BMJ 289:528–530

Nielsen MB, Rasmussen OO, Pedersen JF, Christiansen J (1993) Risk of sphincter damage and anal incontinence after anal dilatation for fissure-in-ano. An endosonographic study. Dis Colon Rectum 36:677–680

Renzi A, Brusciano L, Pescatori M et al (2005) Pneumatic balloon dilation for chronic anal fissure: a prospective, clinical, endosonographic, and manometric study. Dis Colon Rectum 48:121–126

Yucel T, Gonullu D, Oncu M, Koksoy FN, Ozkan SG, Aycan O (2009) Comparison of controlled-intermittent anal dilatation and lateral internal sphincterotomy in the treatment of chronic anal fissures: a prospective, randomized study. Int J Surg 7:228–231

Abcarian H (1980) Surgical correction of chronic anal fissure: results of lateral internal sphincterotomy vs fissurectomy-midline sphincterotomy. Dis Colon Rectum 23:31–36

McDonald P, Driscoll AM, Nicholls RJ (1983) The anal dilator in the conservative management of acute anal fissures. Br J Surg 70:25–26

Hawley PR (1969) The treatment of chronic fissure-in-ano. A trial of methods. Br J Surg 56:915–918

Karamanlis E, Michalopoulos A, Papadopoulos V et al. (2010) Prospective clinical trial comparing sphincterotomy, nitroglycerin ointment and xylocaine/lactulose combination for the treatment of anal fissure. Tech Coloproctol 14(Suppl 1):S21–S23

Boulous PB, Araujo JG (1984) Adeguate internal sphincterotomy for chronic anal fissure: subcutaneous or open technique? Br J Surg 71:360–362

Kortbeek JB, Langevin JM, Khoo RE, Heine JA (1992) Chronic fissure in ano: a randomized study comparing open and subcutaneous lateral internal sphincterotomy. Dis Colon Rectum 35:835–837

Altomare DF, Rinaldi M, Troilo VL, Marino F, Lobascio P, Puglisi F (2005) Closed ambulatory lateral internal sphincterotomy for chronic anal fissures. Tech Coloproctol 9:248–249

Garcia-Aguilar J, Belmonte C, Wong WD, Lowry AC, Madoff RD (1996) Open vs. closed sphincterotomy for chronic anal fissure: long-term results. Dis Colon Rectum 39:440–443

Leong AF, Seow-Choen F (1995) Lateral sphincterotomy compared with anal advancement flap for chronic anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum 38:69–71

Bhardwaj R, Parker MC (2007) Modern perspectives in the management of chronic anal fissures. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 89:472–478

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Altomare, D.F., Binda, G.A., Canuti, S. et al. The management of patients with primary chronic anal fissure: a position paper. Tech Coloproctol 15, 135–141 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-011-0683-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-011-0683-7